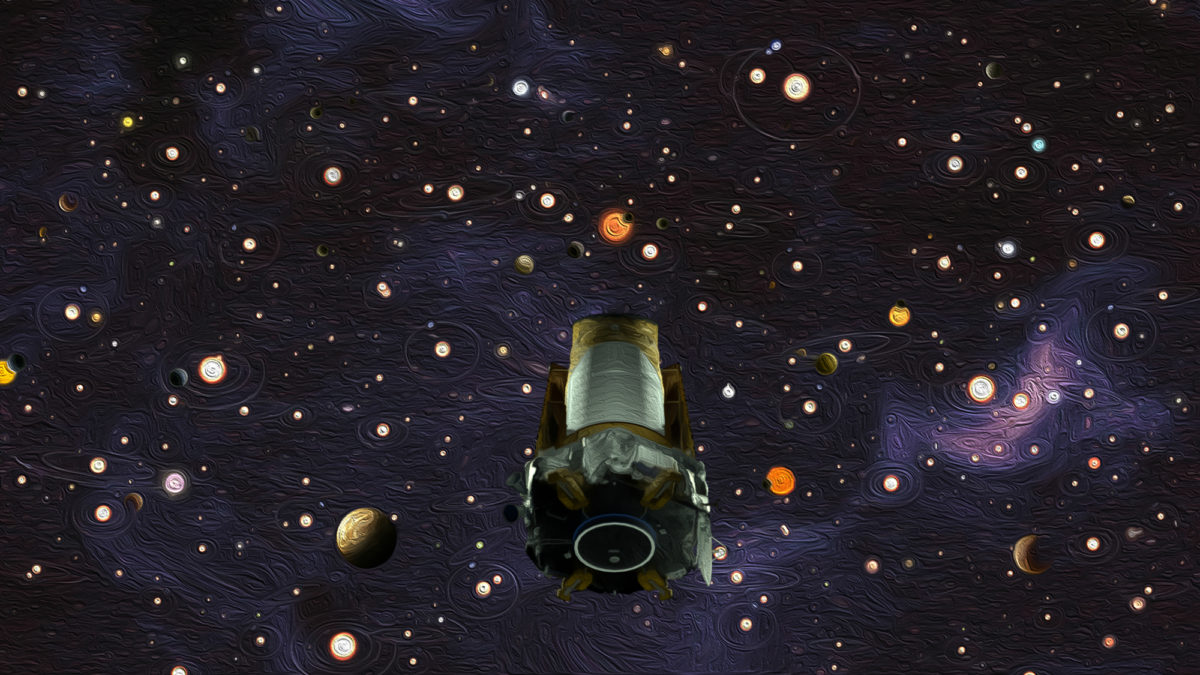

NASA’s groundbreaking Kepler space telescope mission, which revolutionized our understanding of planets orbiting other stars, has come to an end, the agency announced today.

On 11 October, NASA’s Deep Space Network turned its gaze to a spot 170 million kilometers behind Earth in our path around the Sun. There, Kepler turned toward Earth and transmitted the precious data it recently gathered while staring at a patch of sky in the constellation Aquarius. The one-way light travel time between Kepler and Earth is 9.3 minutes.

After that, Kepler tried to get back to work. But on 23 October, NASA learned that the spacecraft had fallen asleep, a side effect of the fact that it was out of fuel. Launched in 2009 on a 3.5-year mission to get a statistical sense of the number of exoplanets in the Milky Way, the telescope has operated for 9 years, thanks to austere fuel use by its mission team.

Without adequate fuel reserves, the spacecraft cannot turn towards Earth to send home the precious pictures it takes while staring at the sky in search of planets crossing in front of stars. NASA has decided to retire the spacecraft by shutting down its radio transmitters, leaving it to drift slowly through space, falling farther and farther behind Earth’s elliptical track around the Sun. Every 40 years or so, Earth and Kepler will cross paths like two ships passing quietly in the night, with Kepler never coming closer than the distance between Earth and the Moon. This orbital dance could theoretically last for millions of years.

To say Kepler revolutionized the field of exoplanet science is an understatement. Through 2008, the year before Kepler’s launch, scientists had confirmed the existences of 340 exoplanets, according to data from the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. Now, there are around 3,800, and Kepler data have contributed to almost 2,700 of those discoveries—about 70 percent.

If you can imagine a type of planetary system, Kepler has probably found it. The potential "water world” of Kepler-22b. An Earth-size planet in a Sun-like star's habitable zone. A tightly-packed solar system with five planets closer to their star than Mercury. The first real-life Tatooine, where a planet orbits two stars. An ancient, 11.2-billion-year-old system named Kepler-444. (Our solar system is just 4.6 billion years old; the Milky Way is about 13.6 billion years old.) Two planets that come within 1.9 million kilometers of each other—just five times the distance between Earth and the Moon. A Uranus-sized planet with a 704-day orbit. The first 8-planet solar system.

Kepler has also seen some cool things closer to home. In 2014, comet Siding Spring passed through its field of view. It saw Neptune dancing with its moons Triton and Nereid in 2015. And on 10 December 2017, it took a photograph of Earth as part of a "wave at Kepler" outreach campaign.

Getting it into space

Like many space missions, Kepler had a long journey just to get to the launch pad. In the 1980s, scientists were getting serious about a space telescope that would be able to stare at stars, watching for light dips caused by transiting exoplanets. But the high-precision detectors required to make such a telescope a reality didn't exist yet. NASA began funding work on the technology, and in 1992, the agency founded the Discovery program, an ongoing series of competitively selected, low-cost planetary science missions. NASA rejected the initial proposals of Kepler to the Discovery program because reviewers estimated such a mission would be similarly expensive to the Hubble Space Telescope. After years of refinements, NASA finally selected Kepler to fly as a Discovery mission in 2001. By then the project had been rejected four times.

The original plan was to launch Kepler by 2006, with a cost cap of $300 million. But NASA delayed development of the space telescope for a year, the cost of the mission's Delta II rocket went up, and there were problems getting the optics and avionics ready to fly. By 2004, the launch date had slipped to 2008, and the cost cap was raised to $515 million. The spacecraft finally lifted off on March 6, 2009.

Kepler’s navigators originally planned for it to orbit the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrangian point in a halo orbit, but the propulsion system required to maintain that orbit turned out to be too expensive. Instead, it launched into an Earth-trailing orbit that circles the Sun once every 372 days.

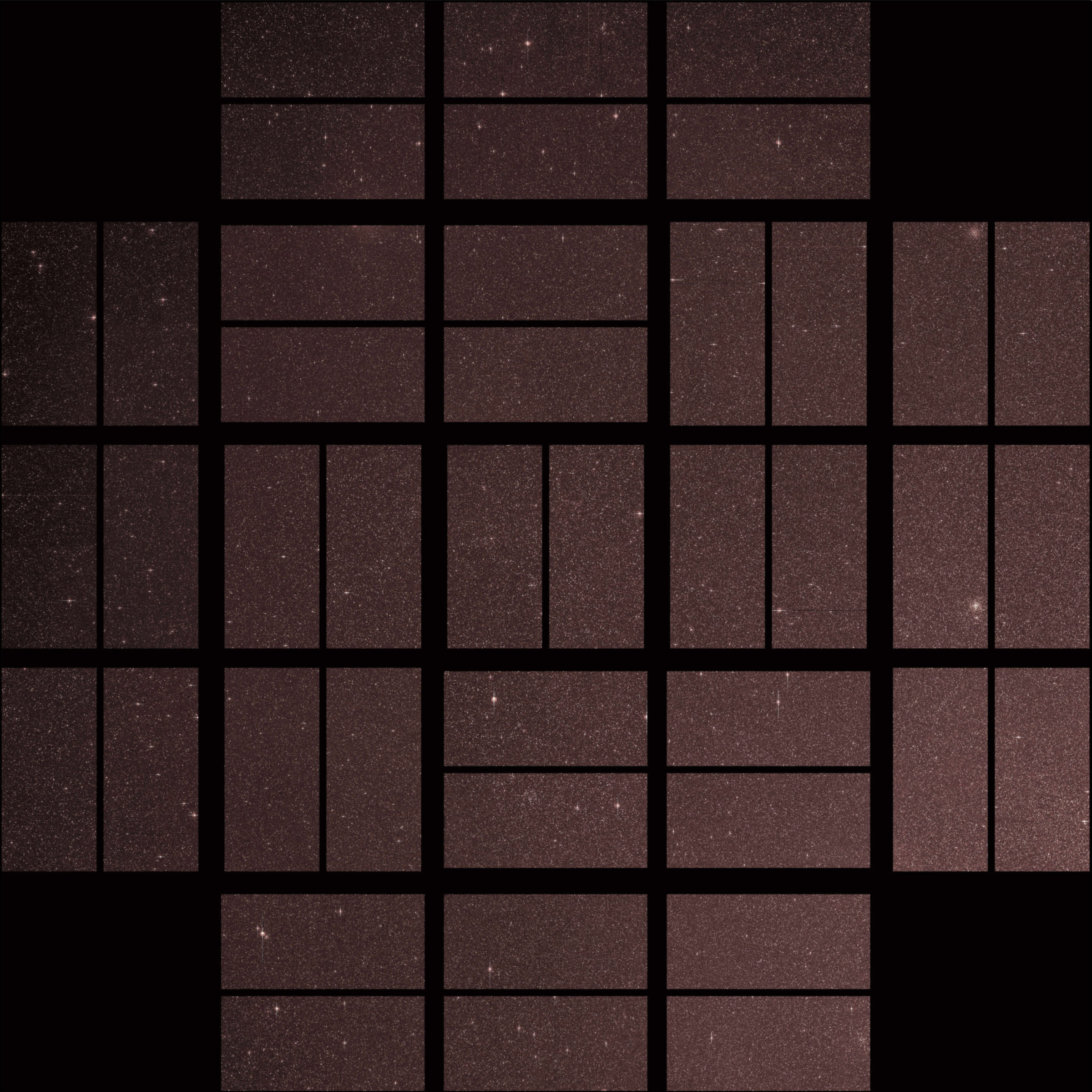

The mission's primary goals were to gather statistics on the different types of exoplanets and exoplanet systems. Kepler achieved that by aiming its 42 CCD detectors at a specific spot in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra. The Kepler field, a part of the sky that you could just about cover with your outstretched hand, contains about 4.5 million stars; scientists focused primarily on about 150,000 of those. A single Kepler image is 95 megapixels, making it the largest space camera ever flown at the time. When the mission's first light image came back to Earth in April 2009, one official wept with joy.

Kepler and K2

Kepler's prime mission was slated to last 3.5 years, from 2009 until November 2012. In January 2010, scientists announced the mission's first batch of five exoplanets, all confirmed with ground-based telescopes. By June, they had found 400 exoplanet candidates for ground-based followup. That number jumped to 1,235 in February 2011, and the findings kept coming in a steady stream after that.

The mission's first major problem happened in July 2012, when one of Kepler’s reaction wheels failed. The telescope only needed three of its four wheels to maintain its precise pointing, so Kepler pushed on, starting its extended mission that November. Then, a second reaction wheel failed in May 2013, meaning Kepler would have to start using its precious supply of fuel to point properly.

It’s the Sun that upsets Kepler’s steady pointing. Light has no mass, but it has momentum, and it pushes on objects in space. (This is the same force that propels solar sails like LightSail 2.) In order for Kepler to keep staring at the same patch of sky in Cygnus and Lyra, it needed three working reaction wheels to control its three axes of pointing freedom (X, Y, and Z, or roll, pitch, and yaw, as you prefer). With only two wheels, engineers lacked control over one of those three axes, so they developed a clever solution: pointing Kepler in a new direction, where the Sun’s rays would be evenly distributed across the telescope. This would cancel out the perturbing force from sunlight, and allow the mission to maintain its steady pointing performance using just two wheels. The only downside was that Kepler would have to more or less stare at what was in front of it — about four patches of sky per year, according to the new plan.

After a few months of testing, the team concluded the strategy worked, and formally proposed to continue the extended Kepler mission under a new moniker: K2. In May 2014, NASA approved K2 for two years. By December, the team announced K2 had already found its first exoplanet.

Earth’s cousin(s)

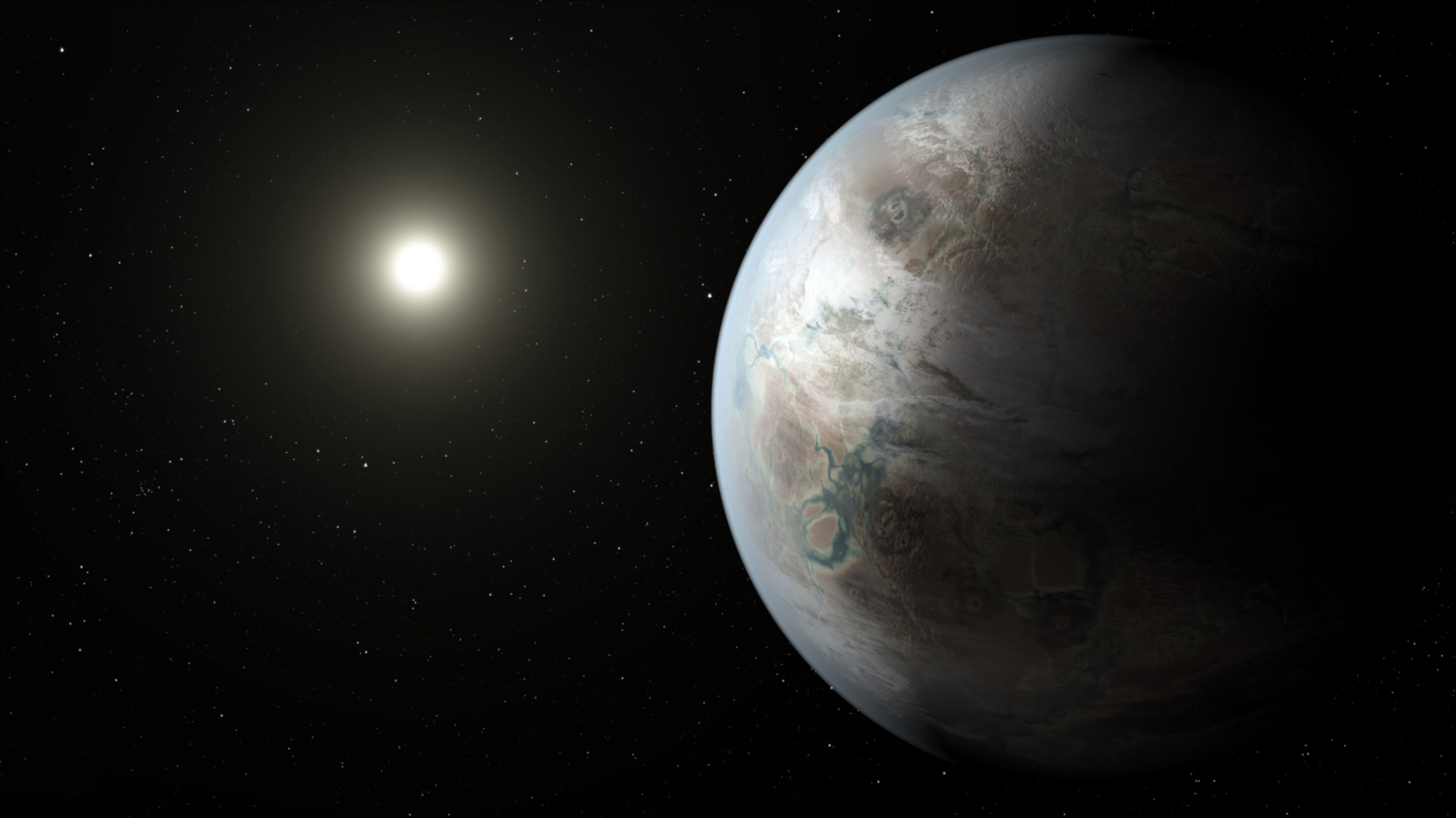

Just a month before K2 was approved, in April 2014, scientists announced Kepler had helped find the type of planet everyone was looking for. About 500 light years from Earth sits a star called Kepler-186. It has four inner planets that are less than 1.5 times the size of Earth. The fifth planet, Kepler-186f, is roughly the size of Earth, right in the star’s habitable zone, where liquid water can exist.

It was the first-ever discovery of a potentially Earth-like planet that might support life. The big difference is Kepler-186f’s star—an M-class dwarf smaller and dimmer than the Sun. At high noon, it would only shine as bright as the Sun at sunset. A year on Kepler-186f lasts just 130 days, and whether or not the planet could support life depends on its atmosphere.

But that was just the beginning. A year later, scientists found a similar planet orbiting a star more like our own. And there are now 30 confirmed planets less than twice the size of Earth in their stars' habitable zones.

Even under the modified K2 mission design, the spacecraft still had to use its thrusters to point towards Earth to send home data. In March 2016, NASA said that Kepler probably had just a little more than two years of fuel remaining. Right on schedule, in March 2018, the agency warned the end was near. In early July, the spacecraft was so low on fuel that NASA halted the current observing campaign—campaign number 18 out of an originally planned 10 for K2—to allow the spacecraft to hibernate until its next scheduled contact with the Deep Space Network on 2 August. The hope was that Kepler would have enough fuel left to turn towards Earth one more time and send home its precious data.

It did. The mission moved on to campaign 19, which, according to NASA updates, was somewhat successful. But Kepler's fuel reserves are so low, there will be no twentieth campaign. The mission is over.

Fortunately, Kepler has already passed the planet-finding baton to a new space telescope, TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. TESS launched in April, and is already collecting science data. Back on Earth, NASA and the National Science Foundation are preparing to follow up on Kepler and TESS exoplanet discoveries using the WIYN telescope on Kitt Peak in southern Arizona.

The next step is to try and figure out the composition of some of these Earth-sized exoplanets’ atmospheres. That work will be done with the next generation of ground-based telescopes, as well as the James Webb Space Telescope.

If we find a true, Earth-like planet orbiting another world, Kepler will have laid the groundwork for the discovery. We won’t be able to thank it, but we’ll know it’s out there, drifting silently around the Sun—a monument to our desire to know our place in the cosmos.

Farewell, Kepler - The Planetary Post with Robert Picardo In October 2018, NASA announced that the Kepler spacecraft, which revolutionized our understanding of planets orbiting other stars, reached the end of its mission. Kepler searched the skies for 9 wonderful years, discovering and confirming thousands of exoplanets. Farewell, Kepler.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth