Jason Davis • Nov 10, 2017

Reminder: The Giant Magellan Telescope is going to be awesome

As someone who writes about space, I am often asked by friends, family and occasionally media representatives to rattle off a list of exciting future space things. If given time to think about it, I usually settle on something tied to the search for life beyond Earth. Whether it's the discovery of microbes in Europa's subsurface ocean or signs of photosynthesis on an exoplanet, I hope I live to see the day when we figure out we're not alone in the universe.

Since 2013, I've been following the construction of the Giant Magellan Telescope, or GMT. The GMT is a next-generation astronomical observatory that will be built in Chile's Atacama Desert. It will have seven, 8.4-meter mirrors, giving it an effective diameter of 24.5 meters in total. For comparison, Hawaii's twin Keck Observatory telescopes have 10-meter-wide mirrors, and they are already dubbed the most scientifically productive optical telescopes in the world.

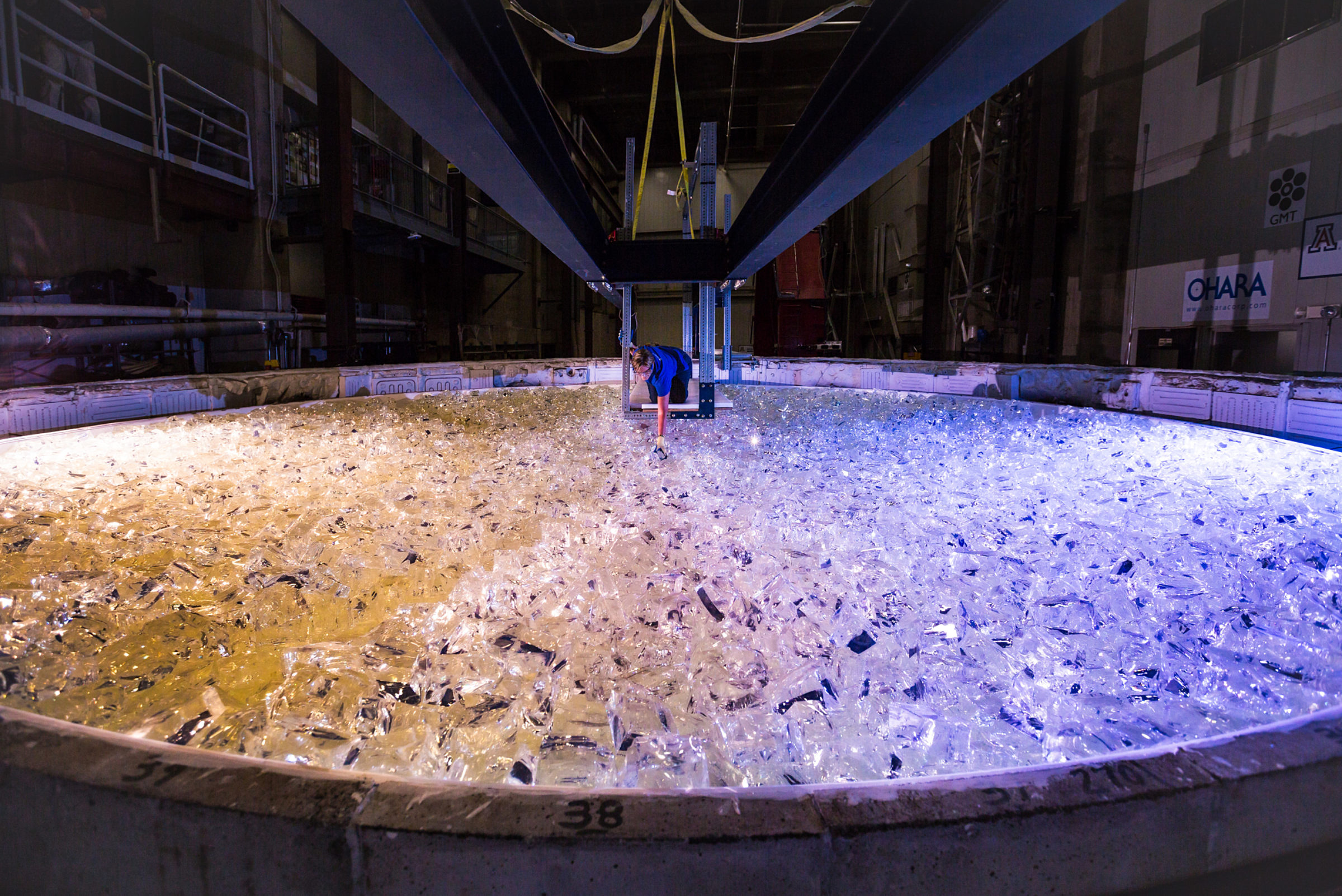

Last week, technicians cast the GMT's fifth mirror at the University of Arizona Steward Observatory Mirror Lab in Tucson, Arizona. The lab marked the milestone with a media event, and though I'd been to the lab twice, I went again—because it's a cool place. (Public tours are available, too, in case you'd like to go.) The process for creating a GMT mirror is fascinating. Chunks of Japanese-made glass are hand-laid in a giant, honeycomb mold. The mold is enclosed in a giant, spinning oven, and as the glass melts it settles into the parabolic curve needed for the telescope. The lab robotically grinds and polishes each mirror, and triple-measures it to make sure it's shaped correctly.

GMT mirror one is already finished and in storage. Mirrors two through four are in various phases of grinding and polishing. Now, as of last week, mirror five is cast, and will slowly cool over the next three months.

The overall GMT project is a little behind schedule. In 2014, I reported the telescope would be partially online in 2020, and that date has since slipped to 2023. GMT officials say there's no single reason for the holdup; it's just the nature of massive, one-of-a-kind science and engineering projects like this. (Program managers working on NASA's Space Launch System and SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rockets will no doubt nod their heads in solidarity).

At the media event, I was reminded again of the GMT's potential to revolutionize the field of exoplanet research. Jared Males, an assistant astronomer at the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory, presented a chart of some known exoplanets the GMT will target. Among them is Proxima Centauri b, an Earth-sized planet orbiting our nearest stellar neighbor. Using adaptive optics, which removes the blurring effect of Earth's atmosphere, the GMT will be able to detect compounds like molecular oxygen, ammonia, and ozone in the atmospheres of Earth-sized planets in their stars' habitable zones, which could indicate the presence of life.

The GMT will also peer back into the universe's first billion years, and closer to home, it will improve our solar system imaging capabilities. Scientists studying ice giants will get sharper views of Uranus and Neptune, which is helpful because those planets don't get spacecraft visitors very often. The GMT is also agile enough to track asteroids.

So far, we know of about 30 Earth-size exoplanets in their stars' habitable zones. Could the GMT, or one of its brethren like the European Extremely Large Telescope or James Webb Space Telescope, make one of the biggest scientific discoveries of all time? The prospect is enticing.

And if we detect nothing? Perhaps it will inspire us to take better care of our own fragile world, which could actually be a cosmic outlier—the only known oasis in the lifeless void of space.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth