Jason Davis • Jul 01, 2015

LightSail Project Manager Passes Torch

The LightSail project manager who helped bring the program from a storage shelf to low-Earth orbit is passing the torch. Doug Stetson, a space mission consultant with 25 years of prior experience at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, will move into an advisory role as work begins on the second LightSail, a solar sailing spacecraft scheduled to launch in fall 2016.

Stetson was brought aboard in 2012 to assess the LightSail program, assemble a new engineering team and secure launch opportunities. Following the success of the LightSail test flight and its accompanying Kickstarter funding campaign, he leaves behind a healthy program preparing to move into its next phase of operations.

Taking over for Stetson as project manager is Georgia Tech’s Dr. Dave Spencer, the principal investigator of Prox-1, LightSail’s partner spacecraft for the 2016 mission. Spencer served as mission manager for the LightSail test flight, and was responsible for planning the spacecraft’s day-to-day operations during its 25-day stay in space.

"Dave and I have really been collaborating on project management up until now and made every key decision together," Stetson says. "And because of the joint mission, it really makes sense to treat these as a joint project. Having one set of eyes managing the overall activities really makes sense, so I’m glad that Dave can do that." In addition to taking over as LightSail project manager, Spencer will reprise his role as mission manager in 2016.

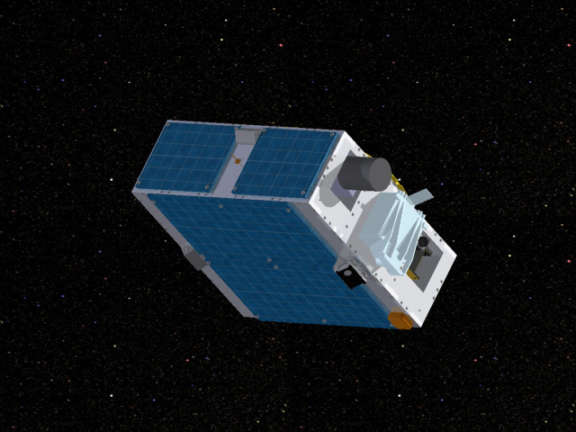

For its full-fledged solar sailing mission, LightSail will initially be enclosed within Prox-1, a 30 by 30 by 60-centimeter microsatellite built by students at Georgia Tech. Prox-1 and LightSail will hitch a ride on SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket to a circular, 720-kilometer orbit during the U.S. Air Force STP-2 mission. STP-2 will be the first operational flight of the Falcon Heavy.

LightSail, which measures 10 by 10 by 30-centimeters, will be deployed from Prox-1. Later, Prox-1 will autonomously track down LightSail and inspect it, closing to just 50 meters. Prox-1 will also hold a position nearby when LightSail deploys its solar sails.

Spencer is no stranger to mission design, navigation and operations. He worked at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory for 17 years, where he was the deputy project manager for the Phoenix Mars lander, mission manager for the Deep Impact and Mars Odyssey projects, and mission designer for Mars Pathfinder and TOPEX/Poseidon spacecraft. Spencer holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in aeronautical and astronautical engineering, and a Ph.D. in aerospace engineering from Georgia Tech.

Spencer joined the Georgia Tech faculty in 2008. He is the co-director of the Space Systems Design Laboratory, an incubator for advanced space technology projects. "My goal in coming to Georgia Tech was to develop the next generation of systems engineers, and to develop a capability to do cutting-edge science and engineering space flight projects," he says.

By fall 2010, Spencer and SSDL completed the preliminary design of Prox-1, a small spacecraft capable of inspecting other objects using thermal and visible imaging. Spencer’s team pitched the concept to the University Nanosat Program, a small satellite competition sponsored by the Air Force.

UNP selected eleven missions, including Prox-1, Spencer said, to receive two years of funding for further development. Following a final down-select round, Prox-1 was the winner of the microsatellite (50 kilograms) class. The project received two more years of funding to finish the spacecraft, along with a potential free ride to orbit.

Remarkably, many Prox-1 team members are undergraduates. "On Prox-1, we have about 55 students, and only a handful are grad students," Spencer says. "We get them involved at the sophomore level, and give them focused responsibilities. By the time they’re juniors and seniors, and they’ve gone off and done some internships, they can do some really good engineering work."

To demonstrate its automated inspection capabilities, Prox-1 needed something to deploy and track in space. The initial target was a Georgia Tech Research Institute-developed CubeSat, Spencer said. But when the secondary spacecraft ran into funding problems and languished, Spencer sought a different partner.

In 2010, an independent review board was assembled to assess LightSail’s flight readiness. Spencer joined the group at the request of a Planetary Society board member, who knew of Spencer’s experience with mission operations. By 2012, Doug Stetson had taken over as project manager. The two spacecraft experts knew each other from their JPL days.

"It’s kind of funny," recalls Spencer. "Doug interviewed me at JPL when I was coming out of college. He was the group supervisor in the mission design section. He was the one guy that actually quizzed me in my interview. He asked me an orbital mechanics question about planetary flybys and had me draw a vector diagram on a whiteboard."

Spencer proposed that LightSail join the Prox-1 mission. It was a win-win: Prox-1 would get its tracking object, and LightSail would get a free ride to orbit. And as a bonus for both missions, LightSail would be an interesting object to image, especially when the spacecraft unfurled its solar sails.

Though Stetson is stepping aside, he will still attend key meetings and workshops and advise the team. "I don’t know if it’s fair to say that LightSail is the most complicated CubeSat mission ever launched—but it’s got to be right up there," he says. As such, "I’m not going anywhere." Stetson will also continue his work as a technical liaison to NASA and the broader space community, and disperse technical results from the missions.

In addition to serving as project manager for LightSail technical and engineering issues, Stetson served as a de facto program manager, regularly reporting LightSail progress to Planetary Society management, donors and board members. Dr. Bruce Betts, director of science and technology projects at The Planetary Society, will take over that role. Betts brings years of Planetary Society project management expertise to the team, and was previously the imaging team lead for the spacecraft’s camera system. As a liaison between the Society and engineering team, he will also be responsible for establishing and modifying contracts with the various organizations involved with LightSail.

Meanwhile, at LightSail's prime contractor, Ecliptic Enterprises Corporation, the LightSail integration and testing effort will be conducted by LightSail test mission veterans Riki Munakata, Stephanie Wong, Alex Diaz (formerly with Half-Band Technologies), and Barbara Plante from Boreal Space. Additional support will come from Ecliptic software systems engineer Brandon Ivy and the engineering team at Moffett Field, Calif.-based Aquila Space. At Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Dr. John Bellardo, Justin Foley and the rest of the PolySat team will continue to provide testing, integration and ground station support.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth