Jason Davis • Sep 30, 2014

More LightSail Day-in-the-Life Multimedia, and a Community Image Processing Challenge

I've had a couple days to organize all of the great photos and videos we captured last week during LightSail's successful day-in-the-life test. In my previous update, I posted the raw deployment video from our primary high-def camera. It takes three minutes and 40 seconds for the sail booms to extend to 90 percent, and while some viewers found the sequence hypnotic, a few got bored—with one commenter saying it was like watching grass grow. If you're in the latter group, this is the video for you:

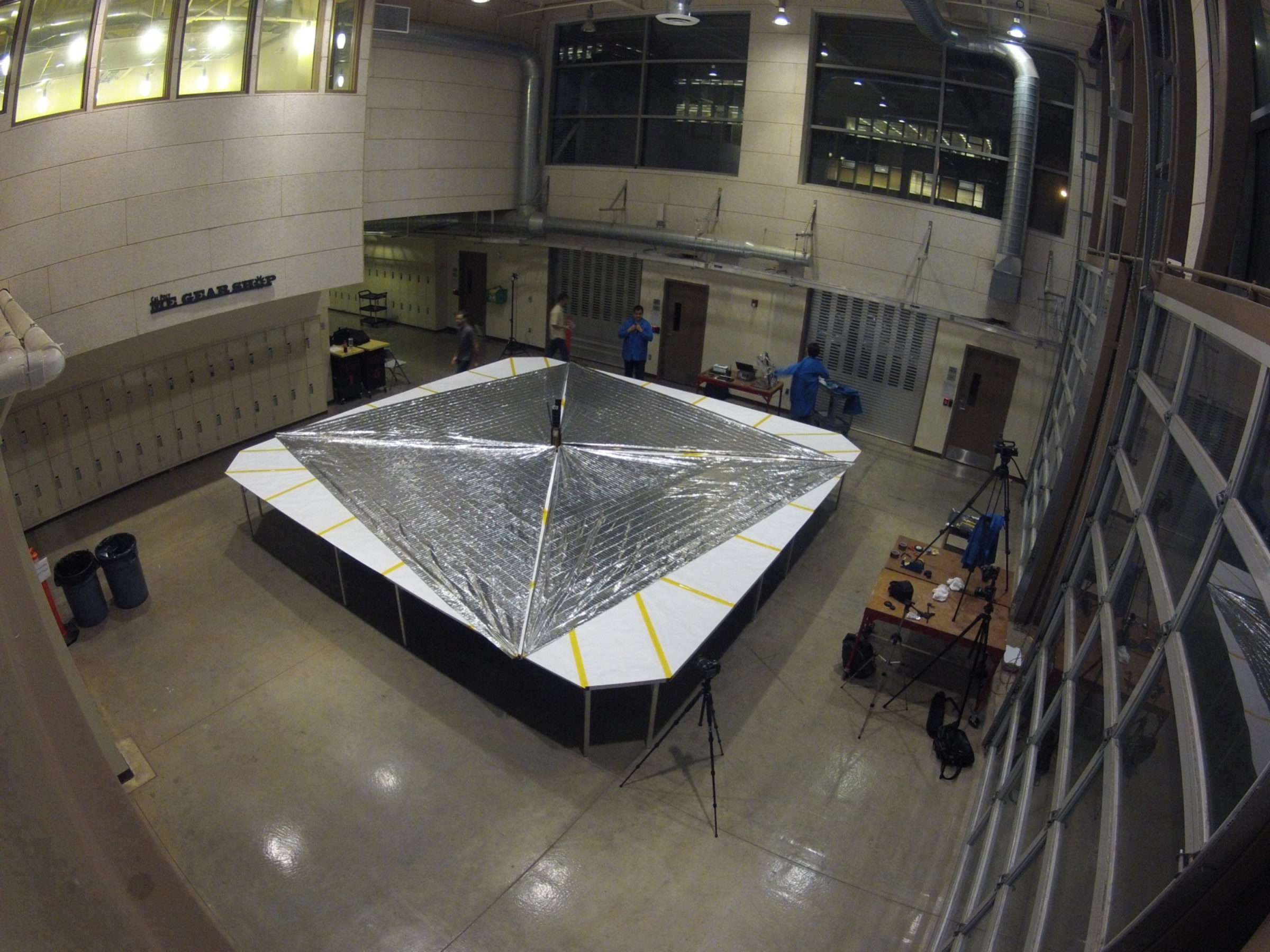

LightSail sail deployment test timelapse This timelapse video of LightSail's sail deployment test at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo on Sept. 23 shows the sails being deployed and tensioned. After the test, a three-person team refolds the sails and stows them back in the spacecraft.Video: Justin Foley

The video comes courtesy of Justin Foley, our Cal Poly team lead. Foley used a ladder to clip his GoPro camera high above the Bonderson Projects Center engineering bay. There's a lot going on here, so let me explain. For the first eight seconds, you're seeing the sail booms deploy to 90 percent. Since the sails hadn't been unfurled for about two years, the team didn't want to apply full tension in case the sails were heavily sticking. Each triangular sail has a metal grommet at each corner. The top of the triangle connects to the spacecraft, and the other two corners connect to booms. The grommets are attached with small springs, which can be measured to check the tension on the sails.

Next, you'll see the booms extend further, in small increments. Once they reach their final length, the team records the final motor revolution count from LightSail's telemetry, and will use that number to deploy the sails in space.

With the sail tensioned correctly, the team manually fluffs out the leading edge of the sails. You'll see this happen from about 26 to 30 seconds. Obviously, no one will be around to do this in space—but the sails won't be held by gravity to a large table, either. If LightSail flies on its 2015 test mission, the spacecraft's onboard cameras will show the team how well the sails unfurl, and adjustments can be made for the full-fledged 2016 mission.

Here's an individual, high-res frame from Foley's video, showing the sails fully deployed and fluffed:

The final part of the timelapse shows the sails being refolded. This is pretty neat to see in person, and is much simpler than I had expected. Three people per triangular sail quadrant start from the leading edge and begin folding the sail lengthwise like an accordion. You might expect that as the folding progresses, the sail would be begin to bulge and billow out of its folds. But remember, the sails are super thin—about one-fourth the thickness of a trash bag—so they stay folded without much fuss. Once each sail has been collapsed into a long strip, it is folded accordion-style again, leaving all three metal grommets exposed for installation back into the CubeSat.

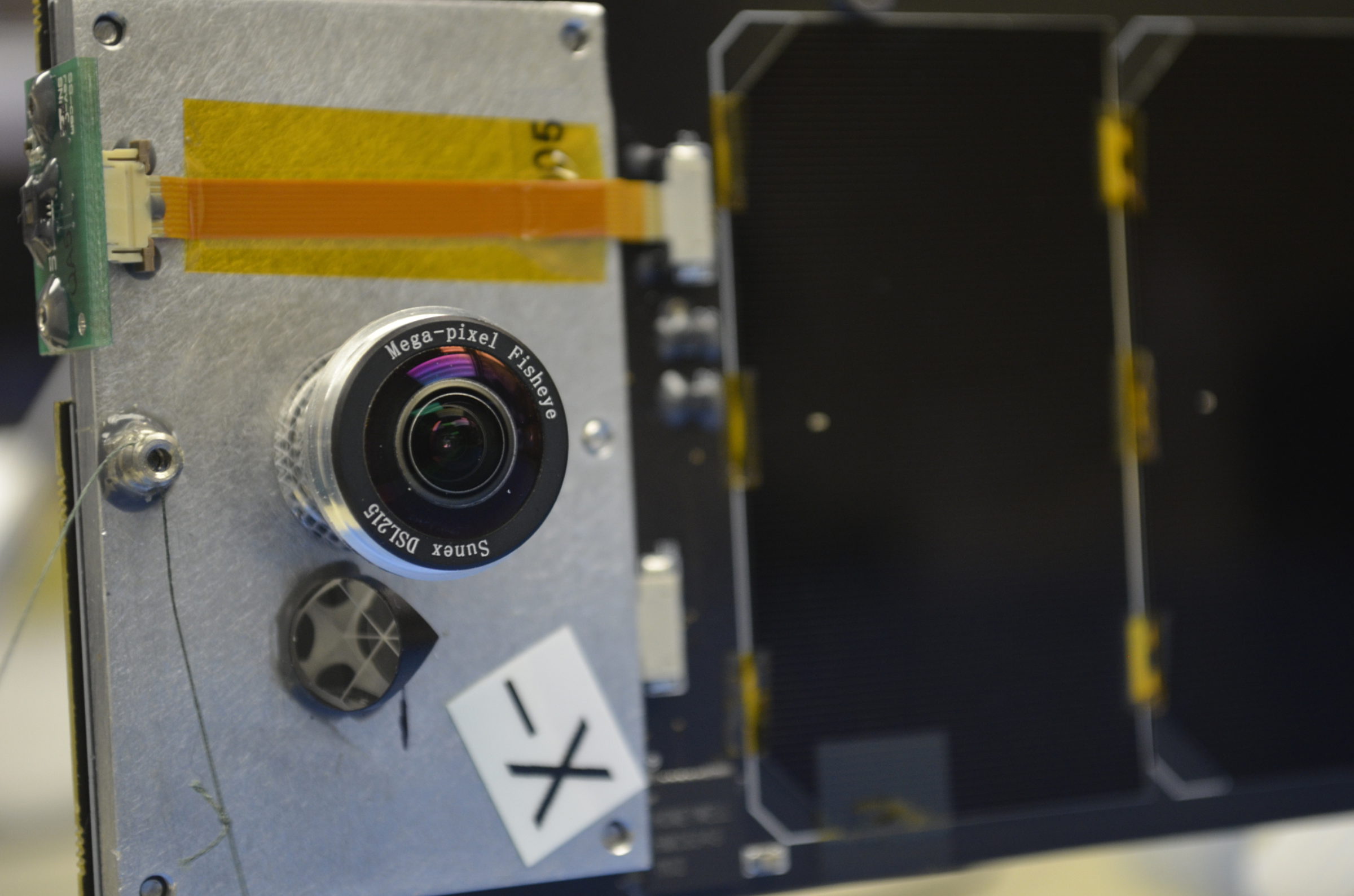

This next video is also pretty cool. It's a screen recording of a Cal Poly ground station computer downloading thumbnail images from LightSail. In the terminal window, you can see that the spacecraft first sent a file and directory listing. LightSail's onboard software is Linux-based, so this step really isn't much different than typing "ls" into a terminal window on, say, a computer running Ubuntu. Next, the spacecraft sent one thumbnail from each camera, which are labelled cameras 0 and 1. This is exactly what faraway spacecraft like Curiosity do—they send home small thumbnails that provide sneak peeks of full-sized images. In our case, this also gives the team the option of not wasting precious ground station passes on bad images.

LightSail sends image thumbnails to its ground station This screen capture video shows LightSail transmitting image thumbnails to its ground station at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. The terminal window indicates the spacecraft sent a directory listing and one thumbnail each from cameras 0 and 1. The "stop spamming" lines show where the ground station waited for LightSail to empty its buffer of telemetry packets that were held while each thumbnail was transferred.Video: Justin Foley

I'll try to explain what the "Waiting for satellite to stop spamming" line means. LightSail transmits telemetry packets every 15 seconds that tell anyone listening how the spacecraft is doing (I'll post some sample telemetry and explain how to read it in a future post). When the ground station commands LightSail to send home a big chunk of data, such as image thumbnails or the images themselves, the telemetry packets get queued in an onboard buffer. After the spacecraft finishes sending its requested data, it spits out all of its stored telemetry. The software that receives and processes the big blocks of requested data ignores these packets as "spam."

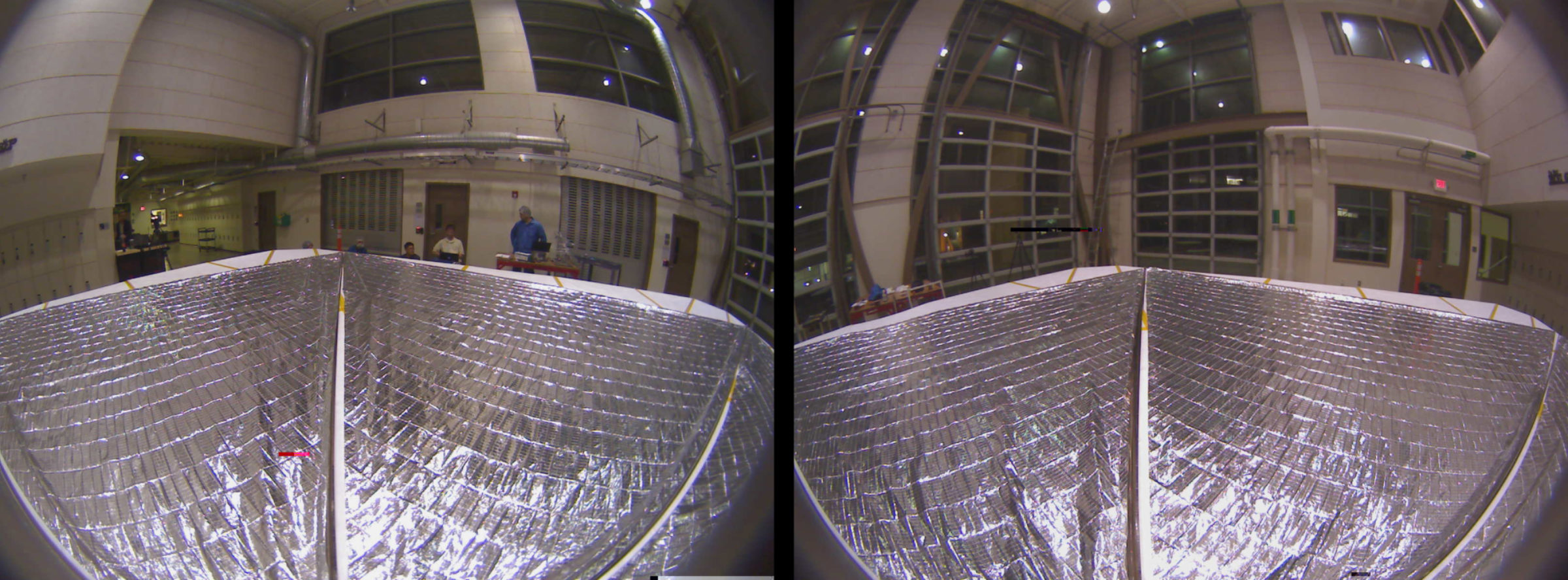

Speaking of onboard camera images, what do they look like?

These are two, 1600 x 1200 resolution images that were manually captured after LightSail's sails were fully tensioned. During the actual sail deployment, the spacecraft's two cameras are programmed to capture an entire sequence of images. Together, these fisheye images give us a 365-degree look at the deployment sequence. Here's a video of the sail deployment test, as seen by the onboard cameras:

LightSail onboard camera timelapse This timelapse was created using images from LightSail's onboard cameras, which captured a sail deployment test at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo on Sept. 23. LightSail is equipped with two fisheye cameras that will record the spacecraft's sail deployment in space.

I was originally going to put the two camera sequences side-by-side, but then I remembered that the cameras are programmed to stagger their images, which gives the team maximum coverage throughout the sail deployment. There's also a natural staggering that gets introduced due to the varying amount of time it takes to compress and store each image, based on how complex the current scene is (for more on this topic, check out my article on the tradeoffs between compression ratio and image size).

Since the two camera images I posted above were captured with the sails fully deployed, my first thought was to try and combine them into a top-down selfie—a rudimentary version of the awesome self-portraits the Mars rovers occasionally take. But doing so requires the help of someone with image processing skills much greater than mine. Fortunately, I know these folks are out there, since their work regularly appears here at The Planetary Society and at places like UnmannedSpaceflight.com.

If anyone wants to give it a try, here are the two raw images:

Please feel free to post a link to any results in the comments, or contact me directly. If it's possible to create a self-portrait using these ground images, we should be able to do it again in space. And there, the payoff will be much greater, since we're hoping to capture some pretty pictures with Earth in the background!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth