Marc Rayman • Jul 30, 2015

Dawn Journal: Descent to HAMO

Dear Descendawnts,

Flying on a blue-green ray of xenon ions, Dawn is gracefully descending toward dwarf planet Ceres. Even as Dawn prepares for a sumptuous new feast in its next mapping orbit, scientists are continuing to delight in the delicacies Ceres has already served. With a wonderfully rich bounty of pictures and other observations already secured, the explorer is now on its way to an even better vantage point.

Dawn takes great advantage of its unique ion propulsion system to maneuver extensively in orbit, optimizing its views of the alien world that beckoned for more than two centuries before a terrestrial ambassador arrived in March. Dawn has been in powered flight for most of its time in space, gently thrusting with its ion engine for 69 percent of the time since it embarked on its bold interplanetary adventure in 2007. Such a flight profile is entirely different from the great majority of space missions. Most spacecraft coast most of the time (just as planets do), making only brief maneuvers that may add up to just a few hours or even less over the course of a mission of many years. But most spacecraft could not accomplish Dawn’s ambitious mission. Indeed, no other spacecraft could. The only ship ever to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations, Dawn accomplishes what would be impossible with conventional technology. With the extraordinary capability of ion propulsion, it is truly an interplanetary spaceship.

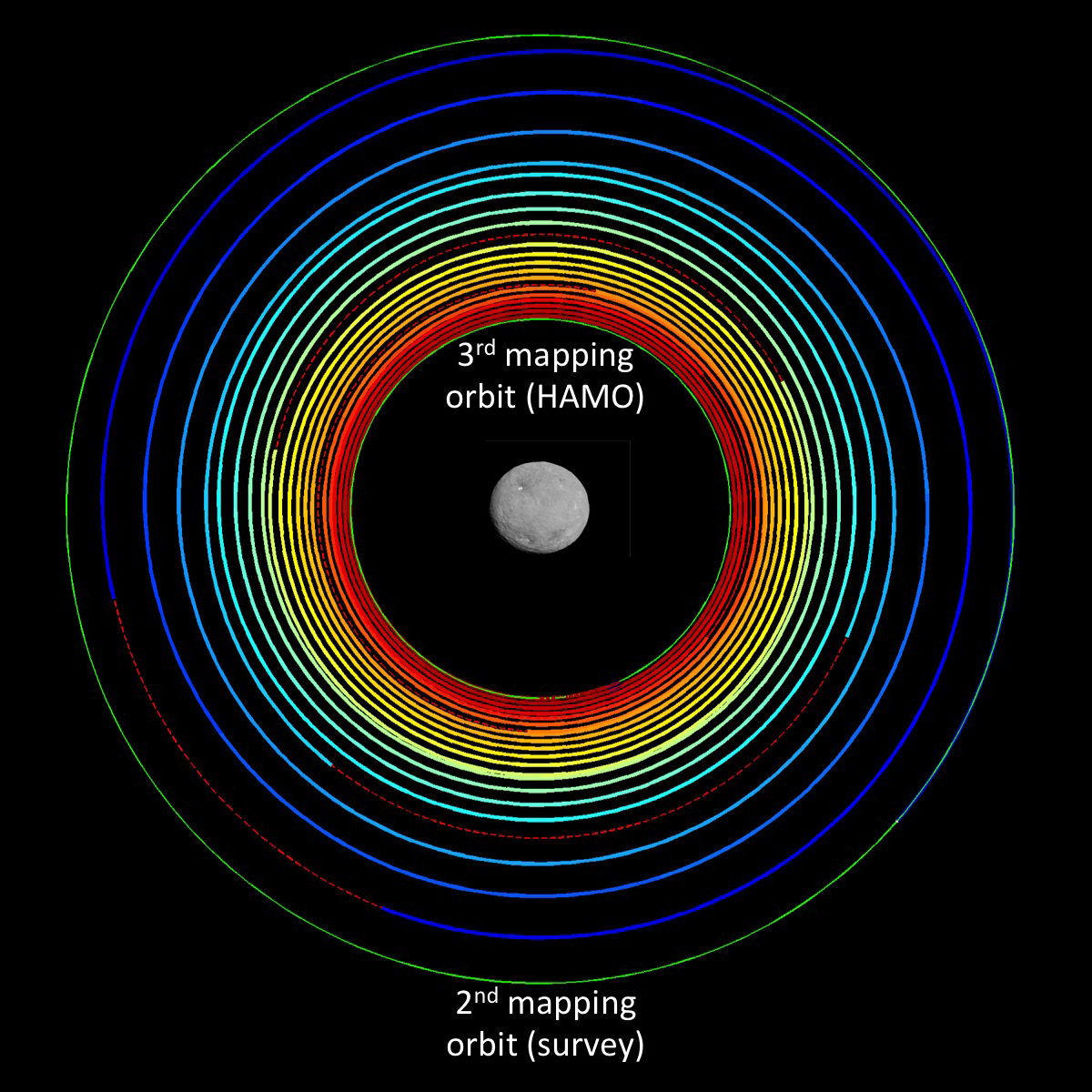

In addition to using its ion engine to travel to Vesta, enter into orbit around the protoplanet in 2011, break out of orbit in 2012, travel to Ceres and enter into orbit there this year, Dawn relies on the same system to fly to different orbits around these worlds it unveils, executing complex and graceful spirals around its gravitational master. After conducting wonderfully successful observation campaigns in its preantepenultimate Ceres orbit 8,400 miles (13,600 kilometers) high in April and May and its antepenultimate orbit at 2,700 miles (4,400 kilometers) in June, Dawn commenced its spiral descent to the penultimate orbit at 915 miles (1,470 kilometers) on June 30. (We will discuss this orbital altitude in more detail below.) A glitch interrupted the maneuvering almost as soon as it began, when protective software detected a discrepancy in the probe’s orientation. But thanks to the exceptional flexibility built into the plans, the mission could easily accommodate the change in schedule that followed. It will have no effect on the outcome of the exploration of Ceres. Let’s see what happened.

Control of Dawn’s orientation in the weightless conditions of spaceflight is the responsibility of the attitude control system. (To maintain a mystique about their work, engineers use the term “attitude” instead of “orientation.” This system also happens to have a very positive attitude about its work.) Dawn (and all other objects in three-dimensional space) can turn about three mutually perpendicular axes. The axes may be called pitch, roll and yaw; left/right, front/back and up/down; x, y and z; rock, paper and scissors; chocolate, vanilla and strawberry; Peter, Paul and Mary; etc., but whatever their names, attitude control has several different means to turn or to stabilize each axis. Earlier in its journey, the spacecraft depended on devices known as reaction wheels. As we have discussed in many Dawn Journals, that method is now used only rarely, because two of the four units have failed. The remaining two are being saved for the ultimate orbit at about 230 miles (375 kilometers), which Dawn will attain at the end of this year. Instead of reaction wheels, Dawn has been using its reaction control system, shooting puffs of hydrazine, a conventional rocket propellant, through small jets. (This is entirely different from the ion propulsion system, which expels high velocity xenon ions to change and control Dawn’s path through space. The reaction control system is used only to change and control attitude.)

Whenever Dawn is firing one of its three ion engines, its attitude control system uses still another method. The ship only operates one engine at a time, and attitude control swivels the mechanical gimbal system that holds that engine, thus imparting a small torque to the spacecraft, providing the means to control two axes (pitch and yaw, for example, or chocolate and strawberry). For the third axis (roll or vanilla), it still uses the hydrazine jets of the reaction control system.

On June 30, engine #3 came to life on schedule at 10:32:19 p.m. PDT to begin nearly five weeks of maneuvers. Attitude control deftly switched from using the reaction control system for all three axes to only one, and controlling the other two axes by tipping and tilting the engine with gimbal #3. But the control was not as effective as it should have been. Software monitoring the attitude recognized the condition but wisely avoided reacting too soon, instead giving attitude control time to try to rectify it. Nevertheless, the situation did not improve. Gradually the attitude deviated more and more from what it should have been, despite attitude control’s efforts. Seventeen minutes after thrusting started, the error had grown to 10 degrees. That’s comparable to how far the hour hand of a clock moves in 20 minutes, so Dawn was rotating only a little faster than an hour hand. But even that was more than the sophisticated probe could allow, so at 10:49:27 p.m., the main computer declared one of the “safe modes,” special configurations designed to protect the ship and the mission in uncertain, unexpected or difficult circumstances.

The spacecraft smoothly entered safe mode by turning off the ion engine, reconfiguring other systems, broadcasting a continuous radio signal through one of its antennas and then patiently awaiting further instructions. The radio transmission was received on a distant planet the next day. (It may yet be received on some other planets in the future, but we shall focus here on the response by Earthlings.) One of NASA’s Deep Space Network stations in Australia picked up the signal on July 1, and the mission control team at JPL began investigating immediately.

Engineers assessed the health of the spacecraft and soon started returning it to its normal configuration. By analyzing the myriad diagnostic details reported by the robot over the next few days, they determined that the gimbal mechanism had not operated correctly, so when attitude control tried to change the angle of the ion engine, it did not achieve the desired result.

Because Dawn had already accomplished more than 96 percent of the planned ion-thrusting for the entire mission (nearly 5.5 years so far), the remaining thrusting could easily be accomplished with only one of the ion engines. (Note that the 96 percent here is different from the 69 percent of the total time since launch mentioned above, simply because Dawn has been scheduled not to thrust some of the time, including when it takes data at Vesta and Ceres.) Similarly, of the ion propulsion system’s two computer controllers, two power units and two sets of valves and other plumbing for the xenon, the mission could be completed with only one of each. So although engineers likely could restore gimbal #3’s performance, they chose to switch to another gimbal (and thus another engine) and move on. Dawn’s goal is to explore a mysterious, fascinating world that used to be known as a planet, not to perform complex (and unnecessary) interplanetary gimbal repairs.

One of the benefits of being in orbit (besides it being an incredibly cool place to be) is that Dawn can linger at Ceres, studying it in great detail rather than being constrained by a fast flight and a quick glimpse. By the same principle, there was no urgency in resuming the spiral descent. The second mapping orbit was a perfectly fine place for the spacecraft, and it could circle Ceres there every 3.1 days as long as necessary. (Dawn consumed its hydrazine propellant at a very, very low rate while in that orbit, so the extra time there had a negligible cost, even as measured by the most precious resource.)

The operations team took the time to be cautious and to ensure that they understood the nature of the faulty gimbal well enough to be confident that the ship could continue its smooth sailing. They devised a test to confirm Dawn’s readiness to resume its spiral maneuvers. After swapping to gimbal #2 (and ipso facto engine #2), Dawn thrust from July 14 to 16 and demonstrated the excellent performance the operations team has seen so often from the veteran space traveler. Having passed its test with flying colors (or perhaps even with orbiting colors), Dawn is now well on its way to its third mapping orbit.

The gradual descent from the second mapping orbit to the third will require 25 revolutions. The maneuvers will conclude in about two weeks. (As always, you can follow the progress with your correspondent’s frequent and succinct updates here.) As in each mapping orbit, following arrival, a few days will be required in order to prepare for a new round of intensive observations. That third observing campaign will begin on August 17 and last more than two months.

Although this is the second lowest of the mapping orbits, it is also known as the high altitude mapping orbit (HAMO) for mysterious historical reasons. We presented an overview of the HAMO plans last year. Next month, we will describe how the flight team has built on a number of successes since then to make the plans even better.

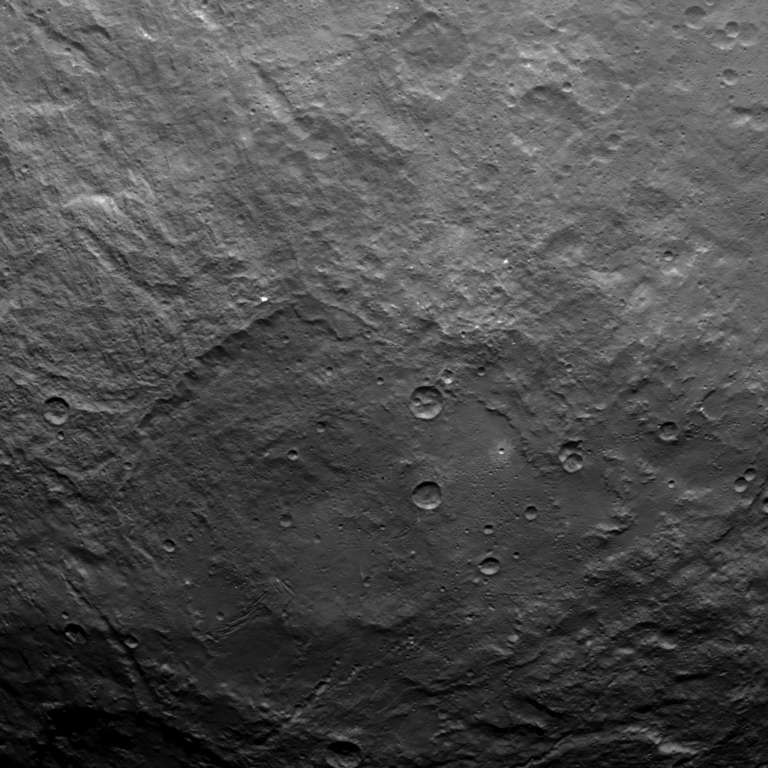

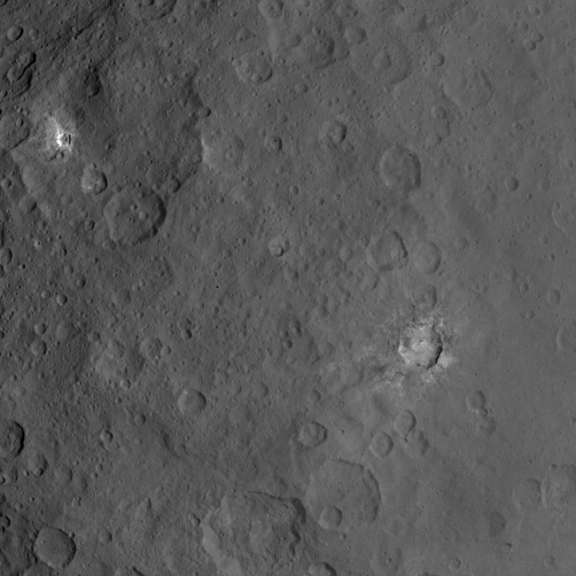

The view of the landscapes on this distant and exotic dwarf planet from the third mapping orbit will be fantastic. How can we be so sure? The view in the second mapping orbit was fantastic, and it will be three times sharper in the upcoming orbit. Quod erat demonstrandum! To see the sights at Ceres, go there or go here.

Part of the flexibility built into the plans was to measure Ceres’ gravity field as accurately as possible in each mapping orbit and use that knowledge to refine the design for the subsequent orbital phase. Thanks to the extensive gravity measurements in the second mapping orbit in June, navigators were able not only to plot a spiral course but also to calculate the parameters for the next orbit to provide the views needed for the complex mapping activities.

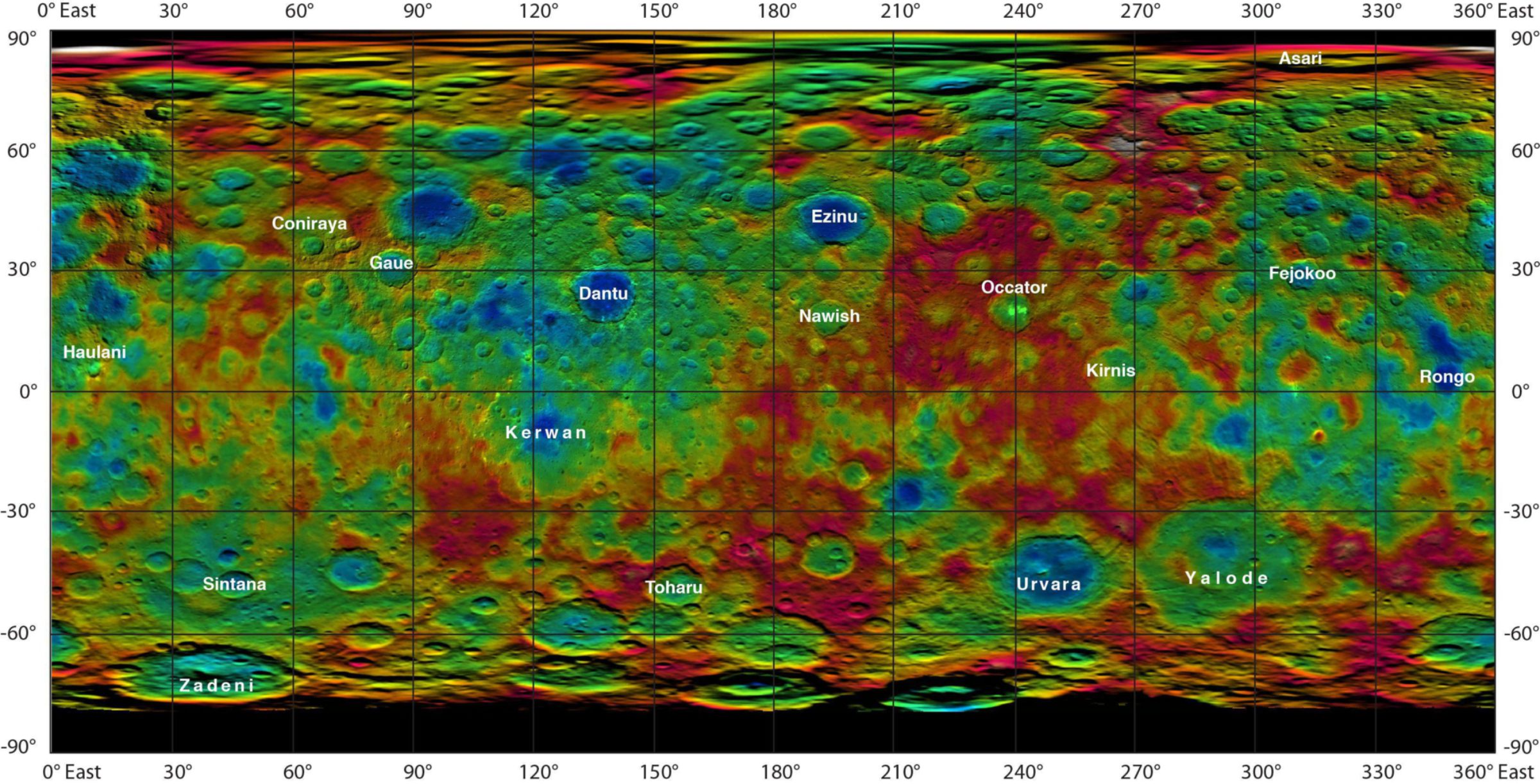

We have discussed some of the difficulty in describing the orbital altitude, including variations in the elevation of the terrain, just as a plane flying over mountains and valleys does not maintain a fixed altitude. As you might expect on a world battered by more than four billion years in the main asteroid belt and with its own internal geological forces, Ceres has its ups and downs. (The topographical map above displays them, and you can see a cool animation of Ceres showing off its topography here.) In addition to local topographical features, its overall shape is not perfectly spherical, as we discussed in May. Ongoing refinements based on Dawn’s measurements now indicate the average diameter is 584 miles (940 kilometers), but the equatorial diameter is 599 miles (964 kilometers), whereas the polar diameter is 556 miles (894 kilometers). Moreover, the orbits themselves are not perfect circles, and irregularities in the gravitational field, caused by regions of lower and higher density inside the dwarf planet, tug less or more on the craft, making it move up and down somewhat. (By using that same principle, scientists learn about the interior structure of Ceres and Vesta with very accurate measurements of the subtleties in the spacecraft’s orbital motions.) Although Dawn’s average altitude will be 915 miles (1,470 kilometers), its actual distance above the ground will vary over a range of about 25 miles (40 kilometers).

In March we summarized the four Ceres mapping orbits along with a guarantee that the dates would change. In addition to delivering exciting interplanetary adventures to thrill anyone who has ever gazed at the night sky in wonder, Dawn delivers on its promises. Therefore, we present the updated table here. With such a long and complex mission taking place in orbit around the largest previously uncharted world in the inner solar system, further changes are highly likely. (Nevertheless, we would consider the probability to be low that changes will occur for the phases in the past.)

| Mapping Orbit | Dawn code name | Tentative dates (further changes are likely) | Altitude in miles (kilometers) | Resolution in feet (meters) per pixel | Resolution compared to Hubble | Orbit period | Equivalent distance of a soccer ball |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RC3 | April 23 – May 9 | 8,400 (13,600) | 4,200 (1,300) | 24 | 15 days | 10 feet (3.0 meters) |

| 2 | Survey | June 6-30 | 2,700 (4,400) | 1,400 (410) | 73 | 3.1 days | 3.3 feet (1.0 meters) |

| 3 | HAMO | Aug 17 – Oct 23 | 915 (1,470) | 450 (140) | 217 | 19 hours | 13 inches (33 cm) |

| 4 | LAMO | Dec 15 – end of mission | 230 (375) | 120 (35) | 850 | 5.5 hours | 3.3 inches (8.5 cm) |

Click on the name of each orbit for a more detailed description. As a reminder, the last column illustrates how large Ceres appears to be from Dawn’s perspective by comparing it with a view of a soccer ball. (Note that Ceres is not only 4.4 million times the diameter of a soccer ball but it is a lot more fun to play with.)

Resolute and resilient, Dawn patiently continues its graceful spirals, propelled not only by its ion engine but also by the passions of everyone who yearns for new knowledge and noble adventures. Humankind’s robotic emissary is well on its way to providing more fascinating insights for everyone who longs to know the cosmos.

Dawn is 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 1.95 AU (181 million miles, or 291 million kilometers) from Earth, or 785 times as far as the moon and 1.92 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 32 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

8:00 p.m. PDT July 29, 2015

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth