Marc Rayman • Apr 01, 2015

Dawn Journal: Preparing to Photograph Ceres

Dear Dawnticipating Explorers,

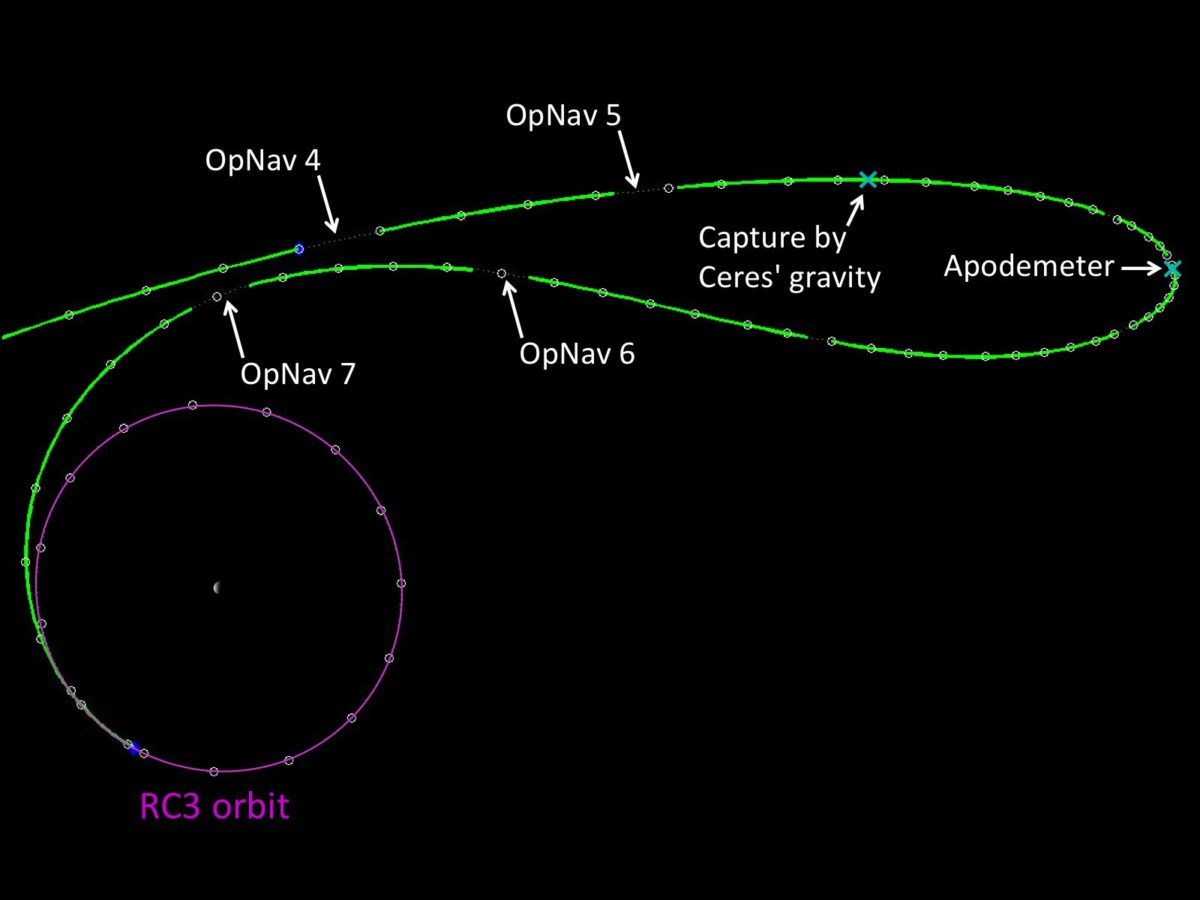

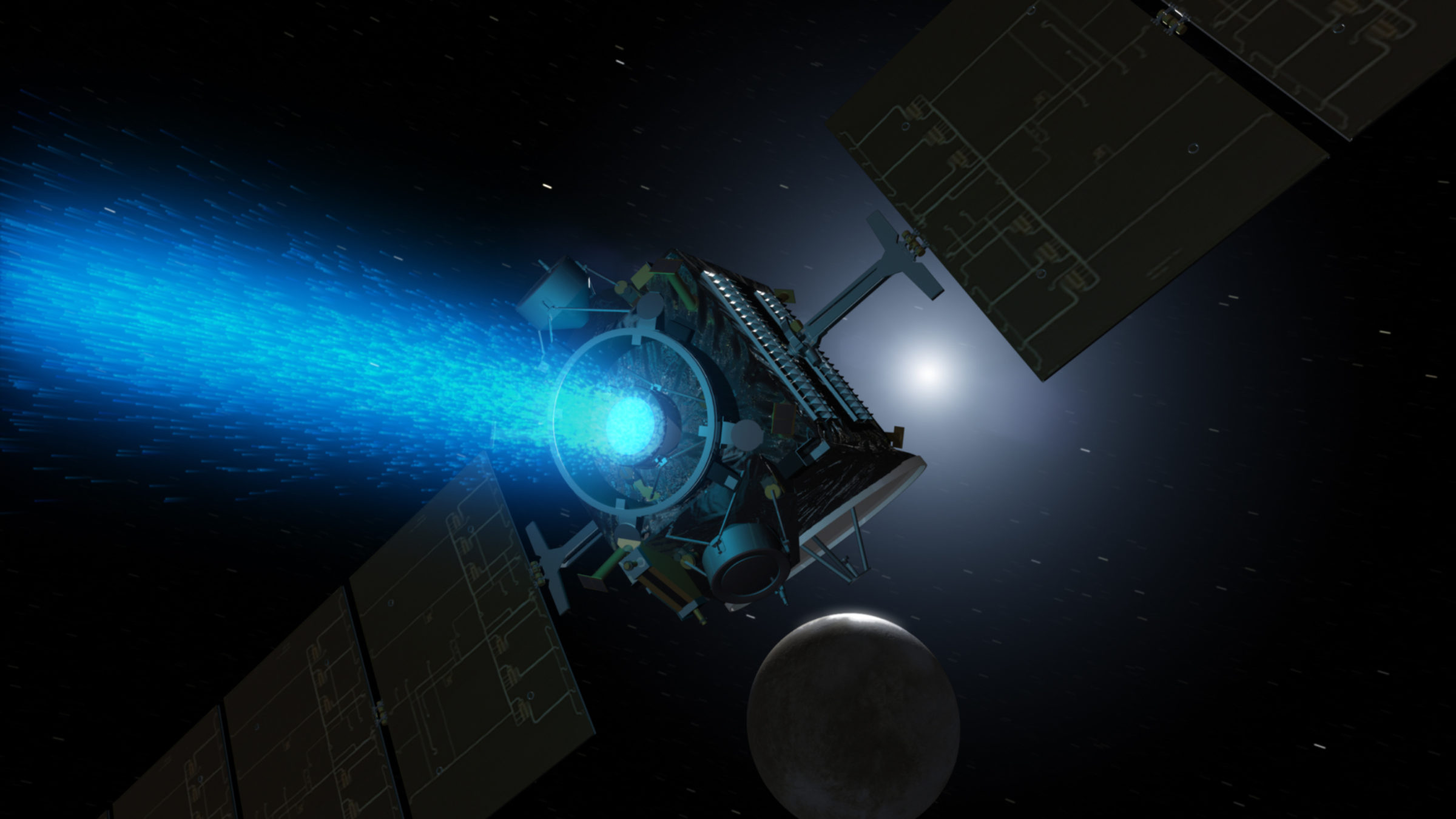

Now orbiting high over the night side of a dwarf planet far from Earth, Dawn arrived at its new permanent residence on March 6. Ceres welcomed the newcomer from Earth with a gentle but firm gravitational embrace. The goddess of agriculture will never release her companion. Indeed, Dawn will only get closer from now on. With the ace flying skills it has demonstrated many times on this ambitious deep-space trek, the interplanetary spaceship is using its ion propulsion system to maneuver into a circular orbit 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometers) above the cratered landscape of ice and rock. Once there, it will commence its first set of intensive observations of the alien world it has traveled for so long and so far to reach.

For now, however, Dawn is not taking pictures. Even after it entered orbit, its momentum carried it to a higher altitude, from which it is now descending. From March 2 to April 9, so much of the ground beneath it is cloaked in darkness that the spacecraft is not even peering at it. Instead, it is steadfastly looking ahead to the rewards of the view it will have when its long, leisurely, elliptical orbit loops far enough around to glimpse the sunlit surface again.

As we describe below, Dawn’s extensive photographic coverage of the sunlit terrain in early May will include these bright spots. They will not be in view, however, when Dawn spies the thin crescent of Ceres in its next optical navigation session, scheduled for April 10 (as always, all dates here are in the Pacific time zone).

As the table here shows, on April 14 (and extending into April 15), Dawn will obtain its last navigational fix before it finishes maneuvering. Should we look forward to catching sight of the bright spots then? In truth, we do not yet know. The spots surely will be there, but the uncertainty is exactly where “there” is. We still have much to learn about a dwarf planet that, until recently, was little more than a fuzzy patch of light among the glowing jewels of the night sky. (For example, only last month did we determine where Ceres’ north and south poles point.) Astronomers had clocked the length of its day, the time it takes to turn once on its axis, at a few minutes more than nine hours. But the last time the spots were in view of Dawn’s camera was on Feb. 19. From then until April 14, while Earth rotates more than 54 times (at 24 hours per turn), Ceres will rotate more than 140 times, which provides plenty of time for a small discrepancy in the exact rate to build up. To illustrate this, if our knowledge of the length of a Cerean day were off by one minute (or less than 0.2 percent), that would translate into more than a quarter of a turn during this period, drastically shifting the location of the spots from Dawn’s point of view. So we are not certain exactly what range of longitudes will be within view in the scheduled OpNav 7 window. Regardless, the pictures will serve their intended purpose of helping navigators establish the probe’s location in relation to its gravitational captor.

Dawn’s gradual, graceful arc down to its first mapping orbit will take the craft from the night side to the day side over the north pole, and then it will travel south. It will conclude its powered flight over the sunlit terrain at about 60 degrees south latitude. The spacecraft will finish reshaping its orbit on April 23, and when it stops its ion engine on that date, it will be in its new circular orbit, designated RC3. (We will return to the confusing names of the different orbits at Ceres below.) Then it will coast, just as the moon coasts in orbit around Earth and Earth coasts around the sun. It will take Dawn just over 15 days to complete one revolution around Ceres at this height. We had a preview of RC3 last year, and now we can take an updated look at the plans.

The dwarf planet is around 590 miles (950 kilometers) in diameter (like Earth and other planets, however, it is slightly wider at the equator than from pole to pole). At the spacecraft’s orbital altitude, it will appear to be the same size as a soccer ball seen from 10 feet (3 meters) away. Part of the basis upon which mission planners chose this distance for the first mapping campaign is that the visible disc of Ceres will just fit in the camera’s field of view. All the pictures taken at lower altitudes will cover a smaller area (but will be correspondingly more detailed). The photos from RC3 will be 3.4 times sharper than those in RC2.

There will be work to do before photography begins however. The first order of business after concluding ion thrusting will be for the flight team to perform a quick navigational update (this time, using only the radio signal) and transmit any refinements (if necessary) in Dawn’s orbital parameters, so it always has an accurate knowledge of where it is. (These will not be adjustments to the orbit but rather a precise mathematical description of the orbit it achieved.) Controllers will also reconfigure the spacecraft for its intensive observations, which will commence on April 24 as it passes over the south pole and to the night side again.

As at Vesta, even though half of each circular orbit will be over the night side of Ceres, the spacecraft itself will never enter the shadows. The operations team has carefully designed the orbits so that at Dawn’s altitude, it remains illuminated by the sun, even when the land below is not.

It may seem surprising (or even be surprising) that Dawn will conduct measurements when the ground directly beneath it is hidden in the deep darkness of night. To add to the surprise, these observations were not even envisioned when Dawn’s mission was designed, and it did not perform comparable measurements during its extensive exploration of Vesta in 2011-2012.

In December, we described the fascinating discovery of an extremely diffuse veil of water vapor around Ceres. How the water makes its way from the dwarf planet high into space is not known. The Dawn team has devised a plan to investigate this further, even though the tiny amount of vapor was sighted long after the explorer left Earth equipped with sensors designed to study worlds without atmospheres.

It is worth emphasizing that the water vapor is exceedingly tenuous. Indeed, it is much less dense than Earth’s atmosphere at altitudes above the International Space Station, which orbits in what most people consider to be the vacuum of space. Our hero will not need to deploy its umbrella. Even comets, which are miniscule in comparison with Ceres, liberate significantly more water.

There may not even be any water vapor at all now because Ceres is farther from the sun than when the Herschel Space Observatory saw it, but if there is, detecting it will be very challenging. The best method to glimpse it is to look for its subtle effects on light passing through it. Although Dawn cannot gaze directly at the sun, it can look above the lit horizon from the night side, searching intently for faint signs of sunlight scattered by sparse water molecules (or perhaps dust lofted into space with them).

For three days in RC3 after passing over the south pole, the probe will take many pictures and visible and infrared spectra as it watches the slowly shrinking illuminated crescent and the space over it. When the spacecraft has flown to about 29 degrees south latitude over the night side, it will no longer be safe to aim its sensitive instruments in that direction, because they would be too close to the sun. With its memory full of data, Dawn will turn to point its main antenna toward distant Earth. It will take almost two days to radio its findings to NASA’s Deep Space Network. Meanwhile, the spacecraft will continue northward, gliding silently high over the dark surface.

On April 28, it will rotate again to aim its sensors at Ceres and the space above it, resuming measurements when it is about 21 degrees north of the equator and continuing almost to the north pole on May 1. By the time it turns once again to beam its data to Earth, it will have completed a wealth of measurements not even considered when the mission was being designed.

Loyal readers will recall that Dawn has lost two of its four reaction wheels, gyroscope-like devices it uses to turn and to stabilize itself. Although such a loss could be grave for some missions, the operations team overcame this very serious challenge. They now have detailed plans to accomplish all of the original Ceres objectives regardless of the condition of the reaction wheels, even the two that have not failed (yet). It is quite a testament to their creativity and resourcefulness that despite the tight constraints of flying the spacecraft differently, the team has been able to add bonus objectives to the mission.

It is important to set the camera exposures carefully. Most of the surface reflects nine percent of the sunlight. (For comparison, the moon reflects 12 percent on average, although as many Earthlings have noticed, there is some variation from place to place. Mars reflects 17 percent, and Vesta reflects 42 percent. Many photos seem to show that your correspondent’s forehead reflects about 100 percent.) But there are some small areas that are significantly more reflective, including the two most famous bright spots. Each spot occupies only one pixel (2.7 miles, or 4.3 kilometers across) in the best pictures so far. If each bright area on the ground is the size of a pixel, then they reflect around 40 percent of the light, providing the stark contrast with the much darker surroundings. When Dawn’s pictures show more detail, it could be that they will turn out to be even smaller and even more reflective than they have appeared so far. In RC3, each pixel will cover 0.8 miles (1.3 kilometers). To ensure the best photographic results, controllers are modifying the elaborate instructions for the camera to take pictures of the entire surface with a wider range of exposures than previously planned, providing high confidence that all dark and all bright areas will be revealed clearly.

Dawn will observe Ceres as it flies from 45 degrees to 35 degrees north latitude on May 3-4. Of course, the camera’s view will extend well north and south of the point immediately below it. (Imagine looking at a globe. Even though you are directly over one point, you can see a larger area.) The territory it will inspect will include those intriguing bright spots. The explorer will report back to Earth on May 4-5. It will perform the same observations between 5 degrees north and 5 degrees south on May 5-6 and transmit those findings on May 6-7. To complete its first global map, it will make another full set of measurements for a Cerean day as it glides between 35 degrees and 45 degrees south on May 7.

By the time it has transmitted its final measurements on May 8, the bounty from RC3 may be more than 2,500 pictures and two million spectra. Mission controllers recognize that glitches are always possible, especially in such complex activities, and they take that into account in their plans. Even if some of the scheduled pictures or spectra are not acquired, RC3 should provide an excellent new perspective on the alien world, displaying details three times smaller than what we have discerned so far.

Dawn activated its gamma ray spectrometer and neutron spectrometer on March 12, but it will not detect radiation from Ceres at this high altitude. For now, it is measuring space radiation to provide context for later measurements. Perhaps it will sense some neutrons in the third mapping orbit this summer, but its primary work to determine the atomic constituents of the material within about a yard (meter) of the surface will be in the lowest altitude orbit at the end of the year.

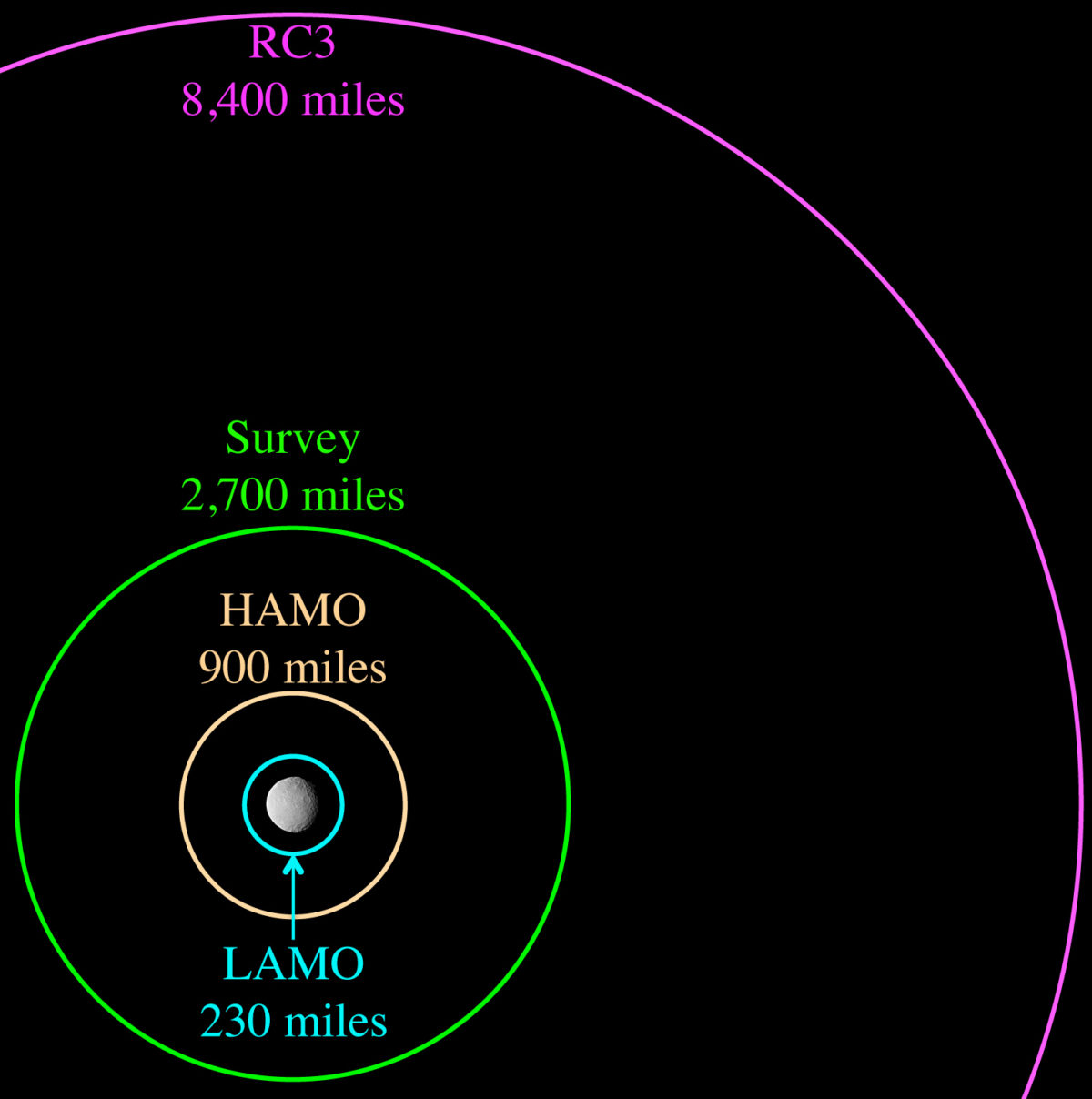

Each orbit is designed to provide a better view than the one before, and Dawn will map the orb thoroughly while at each altitude. The names for the orbits – rotation characterization 3 (RC3); survey; high altitude mapping orbit (HAMO); and low altitude mapping orbit (LAMO) – are based on ancient ideas, and the origins are (or should be) lost in the mists of time. Readers should avoid trying to infer anything at all meaningful in the designations. After some careful consideration, your correspondent chose to use the same names the Dawn team uses rather than create more helpful descriptors for the purposes of these blogs. That ensures consistency with other Dawn project communications. After all, what is important is not what the different orbits are called but rather what amazing new discoveries each one enables.

The robotic explorer will make many kinds of measurements with its suite of powerful instruments. As one indication of the improving view, this table includes the resolution of the photos, and the ever finer detail may be compared with the pictures during the approach phase. For another perspective, we extend the soccer ball analogy above to illustrate how large Ceres will appear to be from the spacecraft’s orbital vantage point.

| Mapping Orbit | Dawn code name | Tentative dates (changes are guaranteed) | Altitude in miles (kilometers) | Resolution in feet (meters) per pixel | Resolution compared to Hubble | Orbit period | Equivalent distance of a soccer ball |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RC3 | April 23 – May 9 | 8,400 (13,500) | 4,200 (1,300) | 24 | 15 days | 10 feet (3.0 meters) |

| 2 | Survey | June 6-30 | 2,700 (4,400) | 1,400 (410) | 72 | 3.1 days | 3.3 feet (1.0 meters) |

| 3 | HAMO | Aug 4 – Oct 15 | 900 (1,450) | 450 (140) | 215 | 19 hours | 13 inches (33 cm) |

| 4 | LAMO | Dec 8 – end of mission | 230 (375) | 120 (35) | 850 | 5.5 hours | 3.3 inches (8.5 cm) |

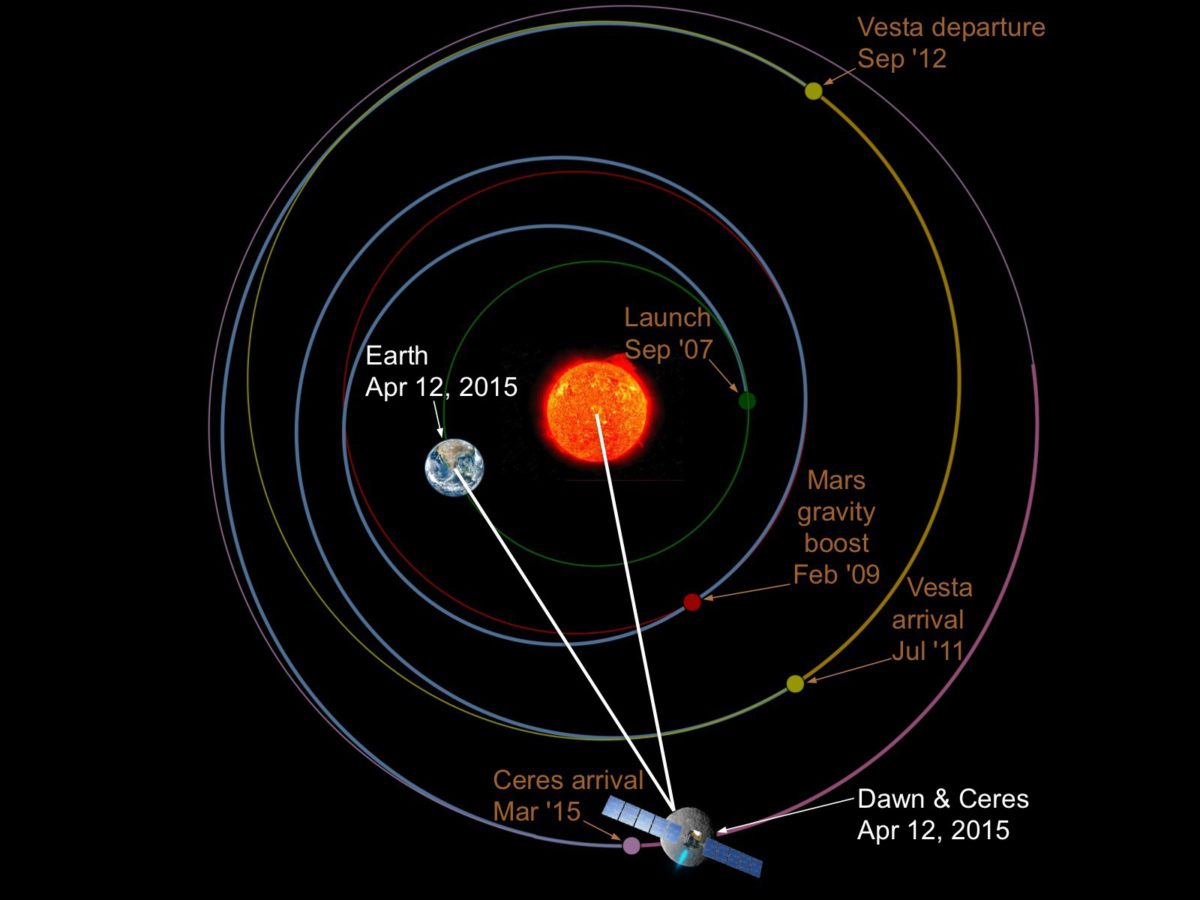

As Dawn orbits Ceres, together they orbit the sun. Closer to the master of the solar system, Earth (with its own retinue, including the moon and many artificial satellites) travels faster in its heliocentric orbit because of the sun’s stronger gravitational pull at its location. In December, Earth was on the opposite side of the sun from Dawn, and now the planet’s higher speed is causing their separation to shrink. Earth will get closer and closer until July 22, when it will pass on the inside track, and the distance will increase again.

In the meantime, on April 12, Dawn will be equidistant from the sun and Earth. The spacecraft will be 2.89 AU or 269 million miles (433 million kilometers) from both. At the same time, Earth will be 1.00 AU or 93.2 million miles (150 million kilometers) from the sun.

Dawn is 35,000 miles (57,000 kilometers) from Ceres, or 15 percent of the average distance between Earth and the moon. It is also 3.04 AU (282 million miles, or 454 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,120 times as far as the moon and 3.04 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 51 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

6:00 p.m. PDT March 31, 2015

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth