Marc Rayman • Jan 30, 2015

Dawn Journal: Closing in on Ceres

Dear Abundawnt Readers

The dwarf planet Ceres is a giant mystery. Drawn on by the irresistible lure of exploring this exotic, alien world, Dawn is closing in on it. The probe is much closer to Ceres than the moon is to Earth.

And now it is even closer…

And now it is closer still!

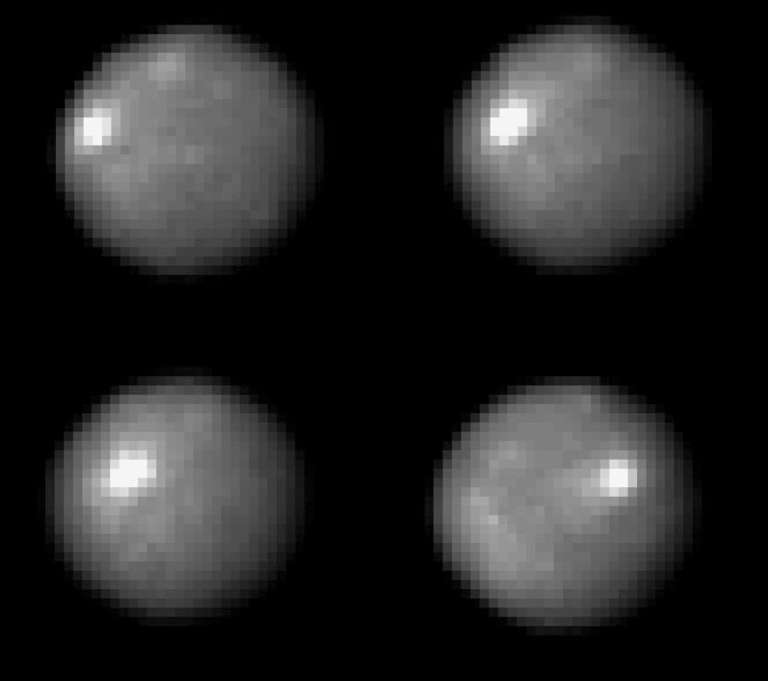

What has been glimpsed as little more than a faint smudge of light amidst the stars for more than two centuries is finally coming into focus. The first dwarf planet discovered (129 years before Pluto), the largest body between the sun and Pluto that a spacecraft has not yet visited, is starting to reveal its secrets. Dawn is seeing sights never before beheld, and all of humankind is along for the extraordinary experience.

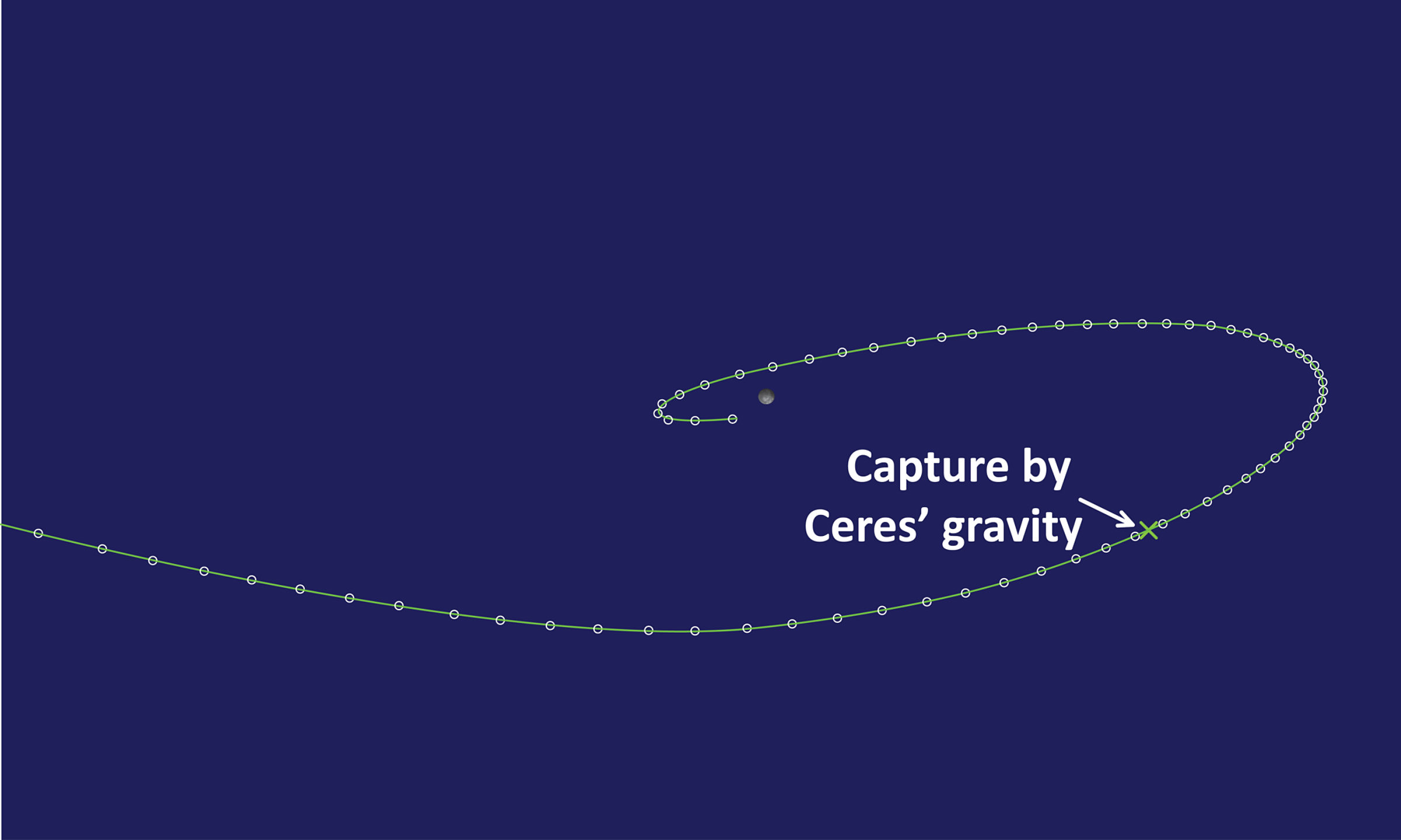

We have had a preview of Dawn’s approach phase, and in November we looked at the acrobatics the spacecraft performs as it glides gracefully into orbit. Now the adventurer is executing those intricate plans, and it is flying beautifully, just the way a seasoned space traveler should.

Dawn’s unique method of patiently, gradually reshaping its orbit around the sun with its ion propulsion system is nearly at its end. Just as two cars may drive together at high speed and thus travel at low speed relative to each other, Dawn is now close to matching Ceres’ heliocentric orbital motion. Together, they are traveling around the sun at nearly 39,000 mph (almost 64,000 kilometers per hour), or 10.8 miles per second (17.4 kilometers per second). But the spaceship is closing in on the world ahead at the quite modest relative speed of about 250 mph (400 kilometers per hour), much less than is typical for interplanetary spaceflight.

Dawn has begun its approach imaging campaign, and the pictures are wonderfully exciting. This month, we will take a more careful look at the plans for photographing Ceres. Eager readers may jump directly to the summary table, but others may want to emulate the spacecraft by taking a more leisurely approach to it, which may aid in understanding some details.

While our faithful Dawn is the star of this bold deep-space adventure (along with protoplanet Vesta and dwarf planet Ceres), the real talent is behind the scenes, as is often the case with celebrities. The success of the mission depends on the dedication and expertise of the members of the Dawn flight team, no farther from Earth than the eighth floor of JPL’s building 264 (although occasionally your correspondent goes on the roof to enjoy the sights of the evening sky). They are carefully guiding the distant spacecraft on its approach trajectory and ensuring it accomplishes all of its tasks.

To keep Dawn on course to Ceres, navigators need a good fix on where the probe and its target are. Both are far, far from Earth, so the job is not easy. In addition to the extraordinarily sophisticated but standard methods of navigating a remote interplanetary spacecraft, using the radio signal to measure its distance and speed, Dawn’s controllers use another technique now that it is in the vicinity of its destination.

From the vantage point of Earth, astronomers can determine distant Ceres’ location remarkably well, and Dawn’s navigators achieve impressive accuracy in establishing the craft’s position. But to enter orbit, still greater accuracy is required. Therefore, Dawn photographs Ceres against the background of known stars, and the pictures are analyzed to pin down the location of the ship relative to the celestial harbor it is approaching. To distinguish this method from the one by which Dawn is usually navigated, this supplementary technique is generally known as “optical navigation.” Unable to suppress their geekiness (or, at least, unmotivated to do so), Dawn team members refer to this as OpNav. There are seven dedicated OpNav imaging sessions during the four-month approach phase, along with two other imaging sessions. (There will also be two more OpNavs in the spiral descent from RC3 to survey orbit.)

The positions of the spacecraft and dwarf planet are already determined well enough with the conventional navigation methods that controllers know which particular stars are near Ceres from Dawn’s perspective. It is the analysis of precisely where Ceres appears relative to those stars that will yield the necessary navigational refinement. Later, when Dawn is so close that the colossus occupies most of the camera’s view, stars will no longer be visible in the pictures. Then the optical navigation will be based on determining the location of the spacecraft with respect to specific surface features that have been charted in previous images.

To execute an OpNav, Dawn suspends ion thrusting and turns to point its camera at Ceres. It usually spends one or two hours taking photos (and bonus measurements with its visible and infrared mapping spectrometer). Then it turns to point its main antenna to Earth and transmits its findings across the solar system to the Deep Space Network.

While it is turning once again to resume ion thrusting, navigators are already starting to extract information from the images to calculate where the probe is relative to its destination. Experts update the design of the trajectory the spacecraft must follow to reach its intended orbital position and fine-tune the corresponding ion thrust flight plan. At the next communications session, the revised instructions are radioed back across the solar system, and then the reliable robot carries them out. This process is repeated throughout the approach phase.

Dawn turned to observe Vesta during that approach phase more often than it does on approach to Ceres, and the reason is simple. It has lost two of its four reaction wheels, devices used to help turn or stabilize the craft in the zero-gravity, frictionless conditions of spaceflight. (In full disclosure, the units aren’t actually lost. We know precisely where they are. But given that they stopped functioning, they might as well be elsewhere in the universe; they don’t do Dawn any good.)

Dawn’s sentient colleagues at JPL, along with excellent support from Orbital Sciences Corporation, have applied their remarkable creativity, tenacity and technical acumen to devise a strategy that allows all the original objectives of exploring Ceres to be met regardless of the condition of the wheels, even the (currently) healthy ones. Your correspondent refers to this as the “zero reaction wheel plan.” One of the many methods that contributed to this surprising resilience was a substantial reduction in the number of turns during all remaining phases of the mission, thus conserving the precious hydrazine propellant used by the small jets of the reaction control system. Guided by their successful experience at Vesta, experts determined that they could accommodate fewer OpNavs during the approach to Ceres, thus saving turns. (We will return to the topic of hydrazine conservation below.)

The images serve several purposes besides navigation. Of course, they provide a tantalizing preview of the intriguing world observed from Earth since 1801. Each picture whets our appetite! What will Ceres look like as it comes into sharper focus? Will we see evidence of a subsurface ocean? What unexpected shapes and structures will we find? What strange new features will show up? Just what is that bright spot? Quite simply: we don’t know. It would be a pretty good idea to send a spacecraft there to find out!

Scientists scrutinize all the photos for moons of Ceres, and OpNavs 3 – 7 will include many extra images with exposures chosen to help reveal moons. In addition, hundreds more pictures will be taken of the space around Ceres in the hours before and after OpNav 3 to allow an even more thorough search.

On two occasions during the approach, Dawn will take images and spectra throughout a complete Ceres rotation of slightly over nine hours, or one Cerean day. During that time, Dawn’s position will not change significantly, so it will be almost as if the spacecraft hovers in place as the dwarf planet pirouettes beneath its watchful eye, exhibiting most of the surface. These “rotation characterizations” (known by the stirring names RC1 and RC2) will provide the first global perspectives.

As Dawn flies into orbit, it arcs around Ceres. In November, we described the route into orbit in detail, and one of the figures there is reproduced here. Dawn will slip into Ceres’ gravitational embrace on the night of March 5 (PST). But as the figure shows, its initial elliptical orbit will carry it to higher altitudes before it swoops back down. As a result, pictures of Ceres will grow for a while, then shrink and then grow again.

Because of the changing direction to Ceres, Dawn does not always see a fully illuminated disk, just as the moon goes through its familiar phases as its position relative to the sun changes. The hemisphere of the moon facing the sun is bright and the other is dark. The half facing Earth may include part of the lit side and part of the dark side. Sometimes we see a full moon, sometimes gibbous, and sometimes a thin crescent.

The table shows what fraction of Ceres is illuminated from Dawn’s perspective. Seeing a full moon would correspond to 100 percent illumination. A half moon would be 50 percent, and a new moon would be zero percent. In OpNav 6, when Ceres is 18 percent illuminated, it will be a delicate crescent, like the moon about four days after it’s new.

OpNav images of a narrow crescent won’t contain enough information to warrant the expenditure of hydrazine in all that turning. Moreover, the camera’s precision optics and sensitive detector, designed for revealing the landscapes of Vesta and Ceres, cannot tolerate looking too close to the sun, even as far from the brilliant star as it is now. Therefore, no pictures will be taken in March and early April when Dawn is far on the opposite side of Ceres from the sun. By the end of April, the probe will have descended to its first observational orbit (RC3), where it will begin its intensive observations.

The closer Dawn is to Ceres, the larger the orb appears to its camera, and the table includes the (approximate) diameter the full disk would be, measured in the number of camera pixels. To display greater detail, each pixel must occupy a smaller portion of the surface. So the “resolution” of the picture indicates how sharp Dawn’s view is.

We also describe the pictures in comparison to the best that have been obtained with Hubble Space Telescope. In Hubble’s pictures, each pixel covered about 19 miles (30 kilometers). Now, after a journey of more than seven years through the solar system, Dawn is finally close enough to Ceres that its view surpasses that of the powerful telescope. By the time Dawn is in its lowest altitude orbit at the end of this year, its pictures will be well over 800 times better than Hubble’s and more than 600 times better than the OpNav 2 pictures from Jan. 25. This is going to be a fantastic year of discovery!

| Beginning of activity in Pacific Time zone | Distance from Dawn to Ceres in miles (kilometers) | Ceres diameter in pixels | Resolution in miles (kilometers) per pixel | Resolution compared to Hubble | Illuminated portion of disk | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dec 1, 2014 | 740,000 (1.2 million) | 9 | 70 (112) | 0.25 | 94% | Camera calibration |

| Jan 13, 2015 | 238,000 (383,000) | 27 | 22 (36) | 0.83 | 95% | OpNav 1 |

| Jan 25 | 147,000 (237,000) | 43 | 14 (22) | 1.3 | 96% | OpNav 2 |

| Feb 3 | 91,000 (146,000) | 70 | 8.5 (14) | 2.2 | 97% | OpNav 3 |

| Feb 12 | 52,000 (83,000) | 121 | 4.9 (7.8) | 3.8 | 98% | RC1 |

| Feb 19 | 28,000 (46,000) | 221 | 2.7 (4.3) | 7.0 | 87% | RC2 |

| Feb 25 | 25,000 (40,000) | 253 | 2.3 (3.7) | 8.0 | 44% | OpNav 4 |

| Mar 1 | 30,000 (49,000) | 207 | 2.9 (4.6) | 6.5 | 22% | OpNav 5 |

| Apr 10 | 21,000 (33,000) | 304 | 2.0 (3.1) | 9.6 | 18% | OpNav 6 |

| Apr 15 | 14,000 (22,000) | 455 | 1.3 (2.1) | 14 | 50% | OpNav 7 |

Some of the numbers may change slightly as Dawn’s trajectory is refined and even as estimates of the strength of Ceres’ gravitational tug improve. (Dawn is already feeling that pull, even though it is not yet in orbit.) Still, this should help you fill out your social calendar for the next few months.

To get views like those Dawn has, you can build your own spaceship and fly it deep into the heart of the main asteroid belt to this intriguing world of rock and ice. Or you can visit our Ceres image gallery to see pictures as soon as they are released. If you chose the first option, use your hydrazine wisely!

As we discussed above, to explore Ceres without the use of the reaction wheels that were essential to the original design, mission controllers have worked very hard to conserve hydrazine. Let’s see how productive that effort has been. (You should be able to follow the story here without careful focus on the numbers. They are here for the more technically oriented readers, accountants and our old friends the Numerivores.)

Dawn launched in Sept. 2007 with 101 pounds (45.6 kilograms) of hydrazine. The ship escaped from Vesta in Sept. 2012, four weeks after the second reaction wheel failed during the climb out of Vesta’s gravitational hole. (By the way, Dawn is now more than one thousand times farther from Vesta than it is from Ceres. It is even farther from Vesta than Earth is from the sun!) At the beginning of the long interplanetary flight to Ceres, it still had 71.2 pounds (32.3 kilograms) left. As it had expended less than one-third of the original supply through the end of the Vesta expedition, that might seem like plenty. But it was not. Without the reaction wheels, subsequent operations would consume much more hydrazine. Indeed, engineers determined that even if they still had the entire amount that had been onboard at launch, it would not be enough. The Ceres objectives were at serious risk!

The flight team undertook an aggressive campaign to conserve hydrazine. They conceived more than 50 new candidate techniques for reducing hydrazine consumption in the 30-month journey to Ceres and the 18 months of Ceres operations and systematically but quickly assessed every one of them.

The team initially calculated that the long interplanetary flight between the departure from Vesta and the beginning of the Ceres approach phase would consume 27.6 pounds (12.5 kilograms) of hydrazine even if there were no errors, no glitches, no problems and no changes in the plans. Following the intensive conservation work, they determined that the spacecraft might instead be able to complete all of its assignments for only 9.7 pounds (4.4 kilograms), an astonishing 65 percent reduction. (Keep track of that mass through the end of the next paragraph.) That would translate directly into more hydrazine being available for the exploration of Ceres. They devised many new methods of conducting the mission at Ceres as well, estimating today that it will cost less than 42.5 pounds (19.3 kilograms) with the zero reaction wheel plan. (If the two remaining wheels operate when called upon in the lowest orbit, they will provide a bonus reduction in hydrazine use.)

Dawn’s two years and four months of interplanetary cruise concluded on Dec. 26, 2014, when the approach phase began. Although the team had computed that they might squeeze the consumption down to as low as 9.7 pounds (4.4 kilograms), it’s one thing to predict it and it’s another to achieve it. Changes to plans become necessary, and not every detail can be foreseen. As recounted in October, the trip was not entirely free of problems, as a burst of cosmic radiation interrupted the smooth operations. Now that the cruise phase is complete, we can measure how well it really went. Dawn used 9.7 pounds (4.4 kilograms), exactly as predicted in 2012. Isn’t flying spacecraft through the forbidding depths of the interplanetary void amazing?

This success provides high confidence in our ability to accomplish all of the plans at Ceres (even if the remaining reaction wheels are not operable). Now that the explorer is so close, it is starting to reap the rewards of the daring 3.0-billion-mile (4.9-billion-kilometer) journey to an ancient world that has long awaited a terrestrial emissary. As Dawn continues its approach phase, our growing anticipation will be fueled by thrilling new pictures, each offering a new perspective on this relict from the dawn of the solar system. Very soon, patience, diligence and unwavering determination will be rewarded with new knowledge and new insight into the nature of the cosmos.

Dawn is 121,000 miles (195,000 kilometers) from Ceres, or half the average distance between Earth and the moon. It is also 3.63 AU (338 million miles, or 544 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,390 times as far as the moon and 3.69 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take one hour to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

7:00 p.m. PST January 29, 2014

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth