Marc Rayman • Dec 01, 2014

Dawn Journal: Looking Ahead at Ceres

Dear Unidawntified Flying Objects,

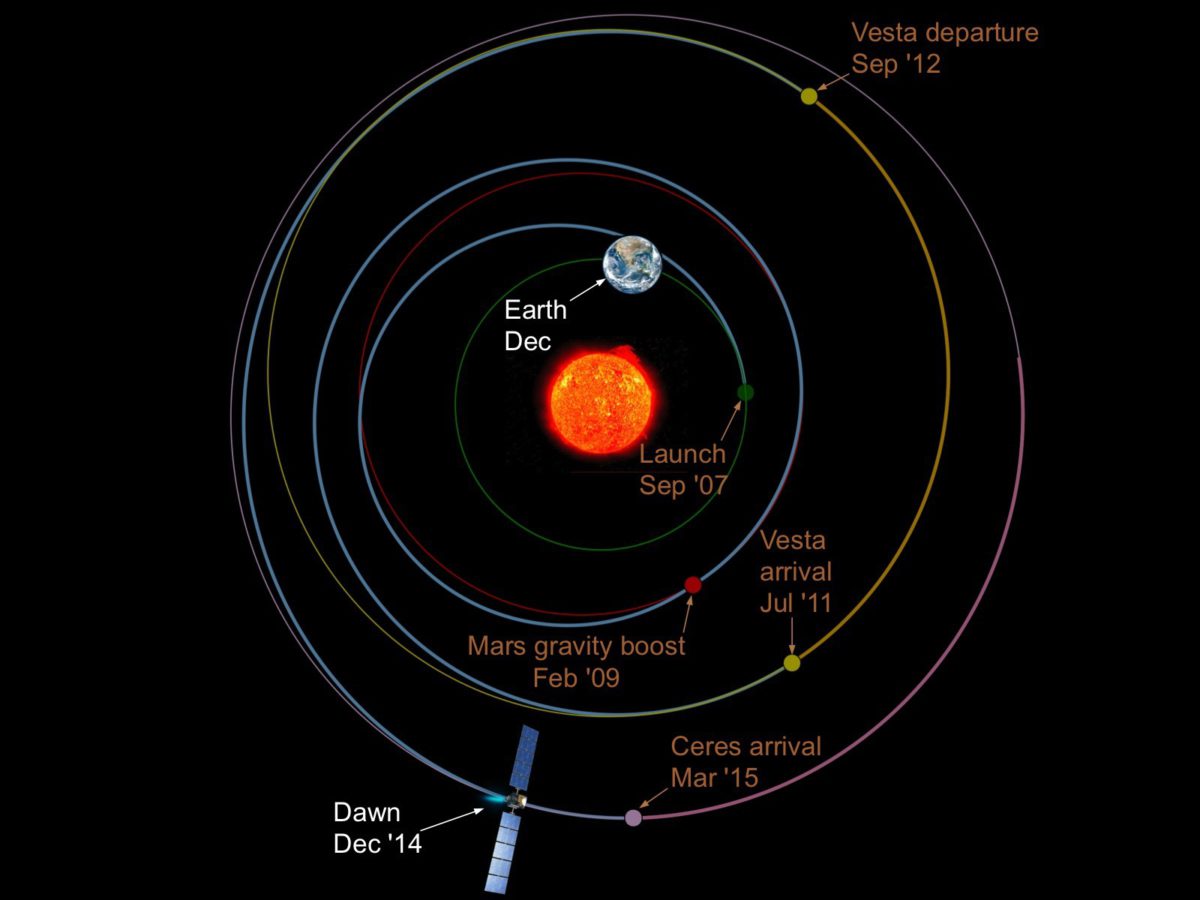

Flying silently and smoothly through the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, Dawn emits a blue-green beam of high velocity xenon ions. On the opposite side of the sun from Earth, firing its uniquely efficient ion propulsion system, the distant adventurer is continuing to make good progress on its long trek from the giant protoplanet Vesta to dwarf planet Ceres.

This month, let’s look ahead to some upcoming activities. You can use the sun in December to locate Dawn in the sky, but before we describe that, let’s see how Dawn is looking ahead to Ceres, with plans to take pictures on the night of Dec. 1.

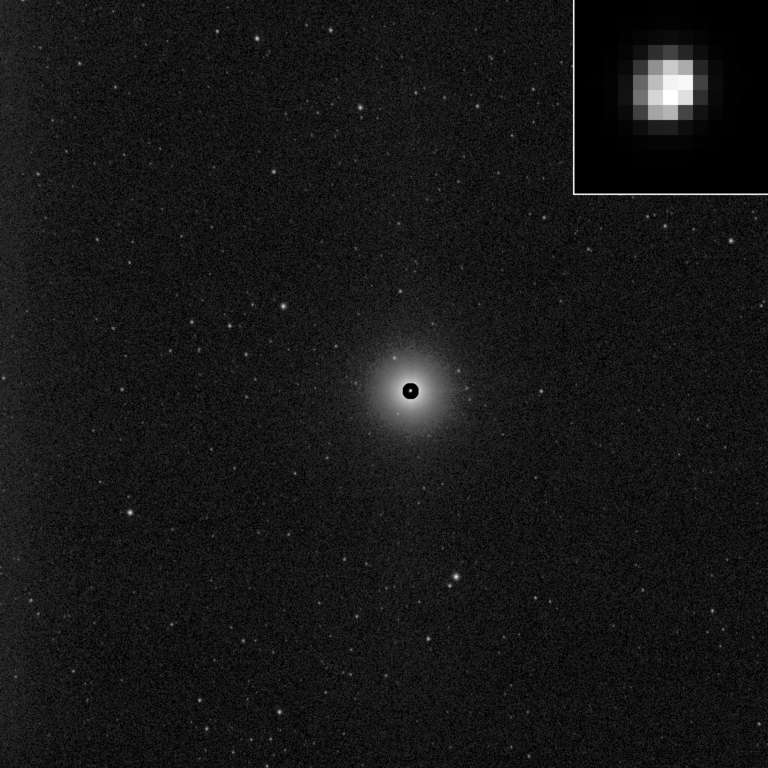

The robotic explorer’s sensors are complex devices that perform many sensitive measurements. To ensure they yield the best possible scientific data, their health must be carefully monitored and maintained, and they must be accurately calibrated. The sophisticated instruments are activated and tested occasionally, and all remain in excellent condition. One final calibration of the science camera is needed before arrival at Ceres. To accomplish it, the camera needs to take pictures of a target that appears just a few pixels across. The endless sky that surrounds our interplanetary traveler is full of stars, but those beautiful pinpoints of light, while easily detectable, are too small for this specialized measurement. But there is an object that just happens to be the right size. On Dec. 1, Ceres will be about nine pixels in diameter, nearly perfect for this calibration.

The images will provide data on very subtle optical properties of the camera that scientists will use when they analyze and interpret the details of some of the pictures returned from orbit. At 740,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers), Dawn’s distance to Ceres will be about three times the separation between Earth and the moon. Its camera, designed for mapping Vesta and Ceres from orbit, will not reveal anything new. It will, however, reveal something cool! The pictures will be the first extended view for the first probe to reach the first dwarf planet discovered. They will show the largest body between the sun and Pluto that has not yet been visited by a spacecraft, Dawn’s destination since it climbed out of Vesta’s gravitational grip more than two years ago.

This will not be the first time Dawn has spotted Ceres. In a different calibration of the camera more than four years ago, the explorer descried its faint destination, far away in both time and space. Back then, still a year before arriving at Vesta, Dawn was more than 1,300 times farther from Ceres than it will be for this new calibration. The giant of the main asteroid belt was an indistinct dot in the vast cosmic landscape. Now Ceres is the brightest object in Dawn’s sky save the distant sun. When it snaps the photos, Ceres will be as bright as Venus sometimes appears from Earth (what astronomers would call visual magnitude -3.6).

To conserve hydrazine, a precious resource following the loss of two reaction wheels, Dawn will thrust with its ion propulsion system when it performs this calibration, which requires long exposures. In addition to moving the spacecraft along in its trajectory, the ion engine stabilizes the ship, enabling it to point steadily in the zero-gravity of spaceflight. (Dawn’s predecessor, Deep Space 1, used the same trick of ion thrusting in order to be as stable as possible for its initial photos of comet Borrelly.)

As Dawn closes in on its quarry, Ceres will grow brighter and larger. Last month we summarized the plan for photographing Ceres during the first part of the approach phase, yielding views in January comparable to the best we currently have (from Hubble Space Telescope) and in February significantly better. The principal purpose of the pictures is to help navigators steer the ship into this uncharted, final port following a long voyage on the interplanetary seas. The camera serves as the helmsman’s eyes. Ceres has been observed with telescopes from (or near) Earth for more than two centuries, but it has appeared as little more than a faint, fuzzy blob farther away than the sun. But not for much longer!

The only spaceship ever built to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations, Dawn’s advanced ion propulsion system enables its ambitious mission. Providing the merest whisper of thrust, the ion engine allows Dawn to maneuver in ways entirely different from conventional spacecraft. In January, we presented in detail Dawn’s unique way of slipping into orbit. In September, a burst of space radiation disrupted the thrust profile. As we saw, the flight team responded swiftly to a very complex problem, minimizing the duration of the missed thrust. One part of their contingency operations was to design a new approach trajectory, accounting for the 95 hours that Dawn coasted instead of thrust. Let’s take a look now at how the resulting trajectory differs from what we discussed at the beginning of this year.

In the original approach, Dawn would follow a simple spiral around Ceres, approaching from the general direction of the sun, looping over the south pole, going beyond to the night side, and coming back above the north pole before easing into the targeted orbit, known by the stirring name RC3, at an altitude of 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometers). Like a pilot landing a plane, flying this route required lining up on a particular course and speed well in advance. The ion thrusting this year had been setting Dawn up to get on that approach spiral early next year.

The change in its flight profile following the September encounter with a rogue cosmic ray meant the spiral path would be markedly different and would require significantly longer to complete. While the flight team certainly is patient — after all, Earth’s robotic ambassador won’t reach Ceres until 213 years after its discovery and more than seven years after launch — the brilliantly creative navigators devised an entirely new approach trajectory that would be shorter. Demonstrating the extraordinary flexibility of ion propulsion, the spacecraft now will take a completely different path but will wind up in exactly the same orbit.

The spacecraft will allow itself to be captured by Ceres on March 6, only about half a day later than the trajectory it was pursuing before the hiatus in thrust, but the geometry both before and after will be quite different. Instead of flying south of Ceres, Dawn is now targeted to trail a little behind it, letting the dwarf planet lead as they both orbit the sun, and then the spacecraft will begin to gently curve around it. (You can see this in the figure above.) Dawn will come to 24,000 miles (38,000 kilometers) and then will slowly arc away. But thanks to the remarkable design of the thrust profile, the ion engine and the gravitational pull from the behemoth of rock and ice will work together. At a distance of 41,000 miles (61,000 kilometers), Ceres will reach out and tenderly take hold of its new consort, and they will be together evermore. Dawn will be in orbit, and Ceres will forever be accompanied by this former resident of Earth.

If the spacecraft stopped thrusting just when Ceres captured it, it would continue looping around the massive body in a high, elliptical orbit, but its mission is to scrutinize the mysterious world. Our goal is not to be in just any arbitrary orbit but rather in the particular orbits that have been chosen to provide the best scientific return for the probe’s camera and other sensors. So it won’t stop but instead will continue maneuvering to RC3.

Ever graceful, Dawn will gently thrust to counter its orbital momentum, keeping it from swinging up to the highest altitude it would otherwise attain. On March 18, nearly two weeks after it is captured by Ceres’ gravity, Dawn will arc to the crest of its orbit. Like a ball thrown high that slows to a momentary stop before falling back, Dawn’s orbital ascent will end at an altitude of 47,000 miles (75,000 kilometers), and Ceres’ relentless pull (aided by the constant, gentle thrust) will win out. As it begins descending toward its gravitational master, it will continue working with Ceres. Rather than resist the fall, the spacecraft will thrust to accelerate itself, quickening the trip down to RC3.

There is more to the specification of the orbit than the altitude. One of the other attributes is the orientation of the orbit in space. (Imagine an orbit as a ring around Ceres, but that ring can be tipped and tilted in many ways.) To provide a view of the entire surface as Ceres rotates underneath it, Dawn needs to be in a polar orbit, flying over the north pole as it travels from the nightside to the dayside, moving south as it passes over the equator, sailing back to the unilluminated side when it reaches the south pole, and then heading north above terrain in the dark of night. To accomplish the earlier part of its new approach trajectory, however, Dawn will stay over lower latitudes, very high above the mysterious surface but not far from the equator. Therefore, as it races toward RC3, it will orient its ion engine not only to shorten the time to reach that orbital altitude but also to tip the plane of its orbit so that it encircles the poles (and tilts the plane to be at a particular orientation relative to the sun). Then, finally, as it gets closer still, it will turn to use that famously efficient glowing beam of xenon ions against Ceres’ gravity, acting as a brake rather than an accelerator. By April 23, this first act of a beautiful new celestial ballet will conclude. Dawn will be in the originally intended orbit around Ceres, ready for its next act: the intensive observations of RC3 we described in February.

Dawn’s route to orbit is no more complex and elegant than what any crackerjack spaceship pilot would execute. However, one of the key differences between what our ace will perform and what often happens in science fiction movies is that Dawn’s maneuvers will comply with the laws of physics. And if that’s not gratifying enough, perhaps the fact that it’s real makes it even more impressive. A spaceship sent from Earth more than seven years ago, propelled by electrically accelerated ions, having already maneuvered extensively in orbit around the giant protoplanet Vesta to reveal its myriad secrets, soon will bank and roll, arc and turn, ascend and descend, and swoop into its planned orbit.

And all this will take place far, far from Earth. Indeed, Dawn is on a very different heliocentric orbit from that of the planet it left behind in 2007. In December, their separate paths will take them to opposite sides of the sun. We will not have a similar celestial arrangement until 2016, by which time the craft will be in its lowest altitude orbit at Ceres. (We invite our future selves to return to the past to tell us here how the view is. __ ) From our terrestrial perspective this year, Dawn will appear to be less than one solar diameter from the sun’s limb on Dec. 9 and 10.

As Earth, the sun, and the spacecraft come closer into alignment, radio signals that go back and forth must pass near the sun. The solar environment is fierce indeed, and it will interfere with those radio waves. While some signals will get through, communication will not be reliable. Therefore, controllers plan to send no messages to the spacecraft from Dec. 4 through Dec. 15; all instructions needed during that time will be stored onboard beforehand. Occasionally Deep Space Network antennas, pointing near the sun, will listen through the roaring noise for the faint whisper of the spacecraft, but the team will consider any communication to be a bonus.

Dawn is big for an interplanetary spacecraft (or for an otherworldly dragonfly, for that matter), with a wingspan of nearly 65 feet (19.7 meters). However, more than 3.8 times as far as the sun, 352 million miles (567 million kilometers) away, humankind lacks any technology even remotely capable of glimpsing it. But we can bring to bear something more powerful than our technology: our mind’s eye. From Dec. 8 to 11, if you block the sun’s blazing light with your thumb, you will also be covering Dawn’s location. There, in that direction, is our faraway emissary to new worlds. It has traveled three billion miles (4.8 billion kilometers) already on its extraordinary extraterrestrial expedition, and some of the most exciting miles are still ahead as it nears Ceres. You can see right where it is. It is now on the far side of the sun.

The sun!

This is the same sun that is more than 100 times the diameter of Earth and a third of a million times its mass. This is the same sun that has been the unchallenged master of our solar system for more than 4.5 billion years. This is the same sun that has shone down on Earth all that time and has been the ultimate source of so much of the heat, light and other energy upon which the planet’s residents have been so dependent. This is the same sun that has so influenced human expression in art, literature, mythology and religion for uncounted millennia. This is the same sun that has motivated scientific studies for centuries. This is the same sun that is our signpost in the Milky Way galaxy. And humans have a spacecraft on the far side of it. We may be humbled by our own insignificance in the universe, yet we still undertake the most valiant adventures in our attempts to comprehend its majesty.

Dawn is 780,000 miles (1.3 million kilometers) from Ceres, or 3.3 times the average distance between Earth and the moon. It is also 3.77 AU (350 million miles, or 564 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,525 times as far as the moon and 3.82 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take one hour and three minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

5:00 p.m. PST November 28, 2014

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth