Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 01, 2006

The Borup Fiord Field Site

In a low valley on an ice-covered island near the top of the world, sulfur-rich waters seep from the top of a 200-meter-thick glacier. Although chilled nearly to freezing temperatures, the waters possess a complex chemistry that likely originates in microbial activity under the ice. Sulfur-rich compounds stain the ice, marking the springs with bright yellow splotches that are easily visible from the air.

Far away, in the outer solar system, lies an icy world whose surface is also stained and splotched with sulfur compounds: Jupiter's moon Europa. Visiting Europa's surface is among the many competing possibilities for the future of outer planet exploration, but no such visit will likely take place for decades. The springs of Borup Fiord may represent the best analog on Earth for a field site on Europa. Scientists hope that by studying the geology, chemistry, and biology of these springs, they'll be able to learn lessons and design the right experiments for the future exploration of the surface of Europa.

The Planetary Society is proud to enable an expedition to this Europa analog in June 2006 by providing key funding. The Planetary Society and its members have long supported a mission to explore Jupiter's moon Europa, and the sulfur springs of Borup Fiord Pass represent a unique opportunity to perform field investigations today that may help us plan for a Europa mission of tomorrow. We'll be closely following the work of the scientists during the expedition and will be posting regular updates on our Planetary Weblog.

The Borup Fiord Field Site

The springs of Borup Fiord Pass are unique on Earth. As they flow or seep onto the surfaces of glaciers, elemental sulfur (S), gypsum (CaSO4), and calcite (CaCO3) precipitate from their waters, while hydrogen sulfide gas (H2S) is released to the air. The deposits stain the surface of the ice and leave telltale landforms behind. The unusual chemistry, in combination with the extremely cold and dry environment, make these springs a potential analog for hydrothermal sites beneath ice on Mars and Europa.

Location

The springs are located in the Canadian high Arctic, on Ellesmere Island, Nunavut territory, at 81ºN, 82ºW, nearly 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) north of the Haughton Mars research station at Devon Island. At this high northern latitude, the Sun fails to rise above the horizon for more than three months every winter, while it circles overhead for three months every summer. The mean annual temperature is -19.7 degrees Celsius (-3.5 degrees Fahrenheit), but it ranges from -36.1 to +5.4 degrees Celsius from January to July (-33 to +42 degrees Fahrenheit). These temperatures are low enough that the ground is permanently frozen to a depth of about 500 meters. Despite the presence of glacial ice, Ellesmere Island is quite dry, receiving only 100 millimeters (4 inches) of rain annually.

Regional and detail location maps of Borup Fiord Pass, Ellesmere Island, Canada

Borup Fiord contains sub-glacial, sulfur-rich springs of interest as possible analogs to Europa. On the detail map, triangles indicate mountain peaks; an oval indicates the location of the sulfur springs; the north-south arrow shows the trend of an "anticline" or upwarping fold in the bedrock; and east-west lines show the locations of faults in the bedrock. All of the white fill on the detail map represents the location of surface ice.Grasby et al. 2003, after Thorsteinsson 1974

Bedrock Geology

The unusual chemistry of the springs probably has its origin in the chemistry of the rocks below the glaciers. The rocks at the surface are primarily marine carbonates, evaporites, and clastics, the types of rocks that would have formed in a tropical seaside setting. None of these rocks exposed near the surface contains much sulfur. However, field geologic mapping studies indicate that there is likely a layer of anhydrite (CaSO4) within 1,500 meters of the surface -- deep enough to lie below the permafrost. There is also a steeply dipping fault in the bedrock very close to the location of the springs. Along the fault, geologists have found massive deposits of the mineral pyrite (Fe2S3) up to two meters thick. It is reasonable to assume that groundwater percolating through buried sulfur-rich rocks could travel quickly toward the surface along such a fault.

The Springs

In three expeditions conducted in July of 1999, 2000, and 2001, researcher Stephen Grasby (assisted by Benoit Beauchamp in 2000) found a total of ten sulfur springs and seeps to be discharging from the surface of a glacier 200 meters thick. They were easy to spot from the air, as they stained the ice with bright yellow deposits of elemental sulfur. They also announced their presence to the nose with the telltale rotten-egg odor of hydrogen sulfide gas.

Some of the springs built interesting structures at their mouths. Where they erupt from the top of the ice, they build little sulfur cones up to 30 centimeters (1 foot) high. A more dramatic spring erupted from the flank of the glacier, spilling a four-meter-tall deposit of sulfur and gypsum. Many of the structures were there in one field season and gone the next. Because the site is only accessible during the summer, it is not known if the springs also flow during the winter.

A sulfur spring discharges from a glacier in Borup Fiord Pass

In this photo from the 2000 field season, a 4-meter-high "flowstone" mound of sulfur and gypsum has formed beneath an outward-flaring horizontal channel. The channel mouth had disappeared when the site was revisited in 2001.Stephen E. Grasby

Water flows from the springs at low rates, the fastest burbling at about a liter per minute. The spring water is a cold 1-2 degrees Celsius (34-36 degrees Fahrenheit), barely above the temperature of the glacial meltwater (itself barely above freezing). The spring water is alkaline with a pH above 9.0 and carries ten times the dissolved solids that are found in the glacial meltwater. In particular, the spring water is nearly saturated with calcium carbonate.

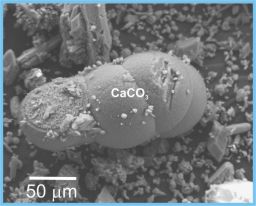

Spherical particles of vaterite

Vaterite is a rare crystal form of calcium carbonate that is observed in the sulfur springs at Borup Fiord Pass, Ellesmere Island, Canada. This represents only the second known occurrence of vaterite on Earth. Its appearance here is probably facilitated by the extremely cold environment and highly basic water chemistry. Such unusual crystal forms of carbonate may be the norm in other cold places in the solar system that have carbonate chemistry, like Mars and Europa.Stephen E. Grasby

The three main sulfur-bearing materials are elemental sulfur (S), gypsum (CaSO4), and hydrogen sulfide gas (H2S). The sulfur in these three minerals is present in three different oxidation states: S0, S-, and S2-. For all three of these states to coexist in the same spring water requires either a very unlikely set of subsurface geologic conditions or the presence of several types of microbial life that can process sulfur from one form to another. In fact, all of the spring waters contain bacteria, including species of Marinobacter, Polaromonas, Burkhoderia, and Pseudomonas.

One particularly interesting find among the materials deposited at the springs was a mineral called vaterite. Vaterite is one of many crystalline forms of calcium carbonate. This is only the second location on Earth where vaterite has been found to occur naturally. Its occurrence is likely facilitated by the extreme cold, alkaline waters, and presence of gypsum. These extreme conditions are rare on Earth but might be more common on other planetary bodies, like Mars or Europa.

A Possible Europa Analog

Lenticulae on Europa

The round, reddish spots in this image, each about 10 kilometers (6 miles) across, are named "lenticulae" (Latin for "freckles"). Generally, reddish features on Europa appear to be younger than the grayer or bluer features. Round features on planets that do not have an obvious impact origin are most often interpreted to be the result of upwelling of hot, less dense material to the surface. This image was composed of color data captured on June 28, 1996, overlaid on a high-resolution image captured on May 31, 1998.NASA / JPL / University of Arizona / University of Colorado

The sulfur springs of Borup Fiord Pass represent a unique opportunity to perform field investigations on Earth of a location that shares some qualities with likely future landing sites on Europa. Europa is a frigid world where the temperatures are so low that the ice on the surface behaves much like rock does on Earth. The interesting parts of Europa are buried almost inaccessibly below thousands of meters of this ice. However, there are places on Europa where the icy surface is stained with what appears to be the remnants of a chemical brew that originated within the ice or even within the salty ocean below it. Studying these stained spots on Europa could yield insights into what is happening deep below the icy moon's solid crust.

The spring system at Borup Fiord Pass might possess several characteristics analogous to Europa's dark spots. There may be chemical similarities: sulfur-bearing materials appear common in both places. There may be hydrological similarities: the subsurface network of cracks and fissures within the glaciers on Ellesmere Island could provide insights to how the plumbing works on Europa. And study of the microbial life beneath the Borup Fiord glaciers could lend insights into the kinds of habitats for life that might exist beneath Europa's crust.

Questions Guiding Research at Borup Fiord Pass

To understand the spring system and its possible applications to Europa science, researchers have identified a set of questions guiding future field study at Borup Fiord Pass:

- Where do the spring waters come from and what materials have they accessed?

- How have they interacted with the materials through which they have passed?

- What causes the relatively warm (1-2ºC) water temperatures?

- How much has biological mediation affected the materials found on the ice surface?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth