Amir Alexander • Feb 13, 2005

The Discovery of a Planet, Part 2: Out of the Six-Planet World

Since humans first set their eyes to the stars, they noticed that a few of these bright objects behaved differently from the others. Whereas all the stars moved together, revolving around the Earth once every 24 hours, five appeared to move within the firmament among the other stars. Accordingly, they were named “planets,” meaning “wanderers” in Greek. By the 17th century leading astronomers, following the teachings of Copernicus, had recognized that the planets revolve around the Sun, and that the Earth itself is also a planet. This brought the total number of planets to six: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

All of these planets had been known since antiquity, and their progress in the sky measured and recorded carefully for nearly 2000 years. Their number seemed so well established that astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571 - 1630), who was the first to correctly calculate the orbits of the planets, devoted a large part of his Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596) to explaining why there had to be exactly six planets. It was a comforting view of a closed and familiar “system of the world,” which accorded well with prevailing beliefs in an orderly universe guided by divine wisdom.

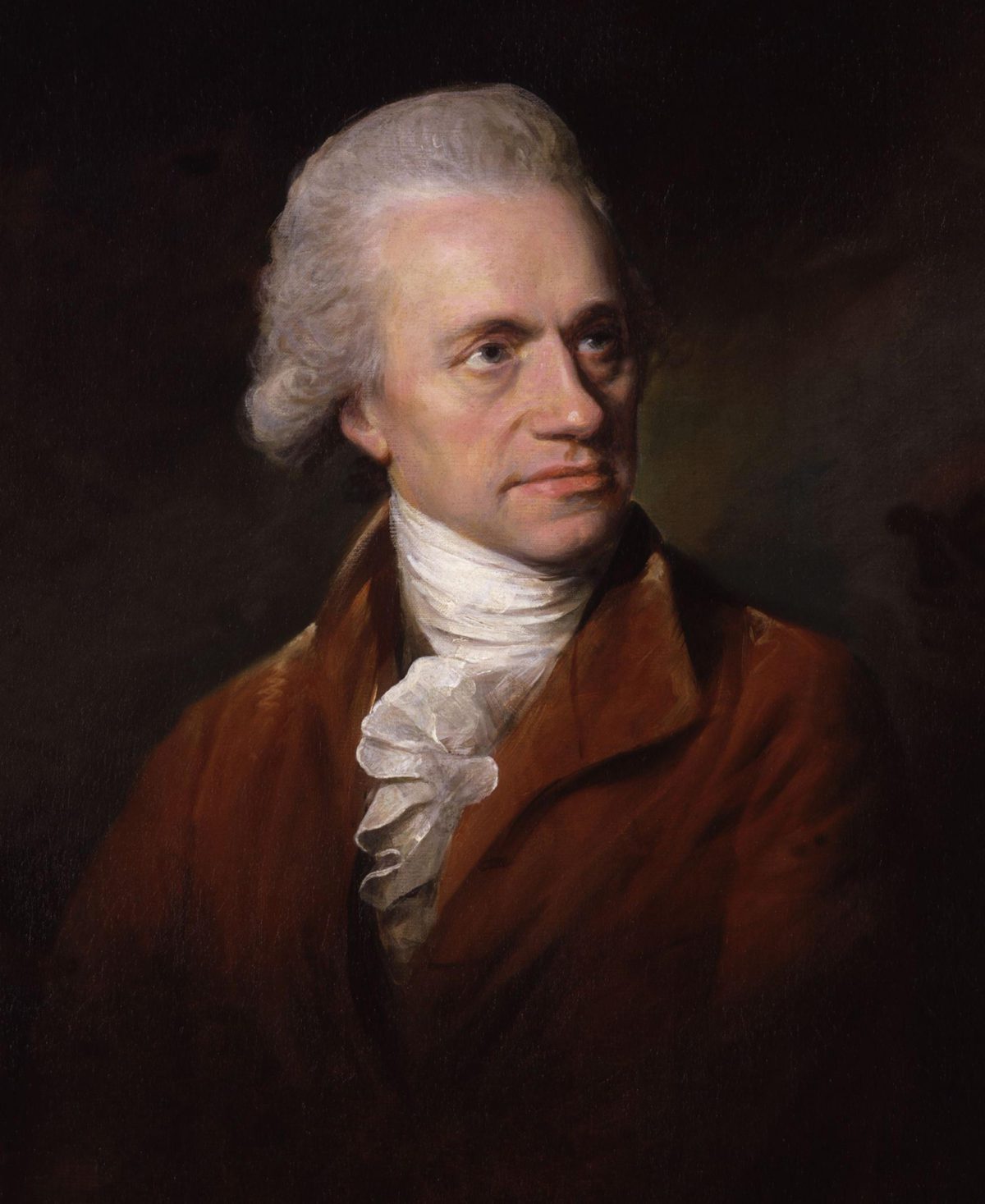

But in 1781 the system of the planets received a jolt from which it would never recover. On the 13th of March William Herschel, a German-born Englishman, master craftsman and dedicated astronomer, trained his 6.2 inch reflector telescope at the sky. “While I was examining the small stars in the neighborhood of H Geminorum,” he wrote later, “I perceived one that was visibly larger than the rest.” Further observations showed that the large “star” appeared to be moving among the other stars, and it was soon recognized as a planet, orbiting the Sun beyond Saturn. After several name changes which included “The Georgian Star” (Herschel’s own preference) and simply “Herschel,” the seventh planet became known as Uranus.

Once the lid was blown off the old six-planet system, there no longer seemed to be an upper limit to the number of possible planets. If Uranus had been hiding all these centuries in the far reaches of the Solar System, could there not be other planets lurking even further away? A close analysis of the orbits of Saturn and Uranus showed that this might indeed be the case. Something, it appeared, was causing perturbations in the smooth elliptical orbits of these two outer planets. The most likely explanation was that an unknown planet was exerting a gravitational pull on its neighbors, causing them to stray from their calculated orbits. Finding that planet, or even figuring out where to look for it, proved to be a daunting task.

When the 8th planet, now known as Neptune, was finally detected in 1846, it was the occasion of one of the most celebrated controversies in the history of science. Two young astronomers – John Couch Adams in England, and Urbain J. J. Leverrier in France – had independently calculated near-identical orbits for the missing planet based on the orbital irregularities of Saturn and Uranus. Being relatively unknown and lacking professional standing, both had trouble getting observational astronomers to follow up on their calculations and search for the planet. Finally, on the night of September 23, 1846, astronomer Johann Galle of the Berlin Observatory tested Leverrier’s prediction and almost immediately found the planet. The priority dispute that followed between Adams and Leverrier and their respective champions was to rock the astronomical community in both England and France for decades to come.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth