Justin Cowart • May 07, 2018

Refreshing the Viking Orbiter views of Mars

A few years ago, I ran across a copy of NASA Special Publication 441, Viking Orbiter Views of Mars, at the Prairie Archives in Springfield, IL. This book was originally published in 1978 to highlight the discoveries that the Viking program was in the process of making. As I flipped through the pages, I saw hundreds of spectacular images ranging from birds’ eye views of the entire planet, to the weather, and to the seasonal heartbeat of the polar ice caps. And I wondered to myself – why hadn’t many of these images been reprocessed? They were fuzzy, grainy and oversaturated. Mosaics, painstakingly and lovingly constructed with paper and scissors, showed seams that often made interpretation of details difficult. These were postcards from the Solar System – a tourist’s idea of what other planets were like, but clearly not the experience of being there.

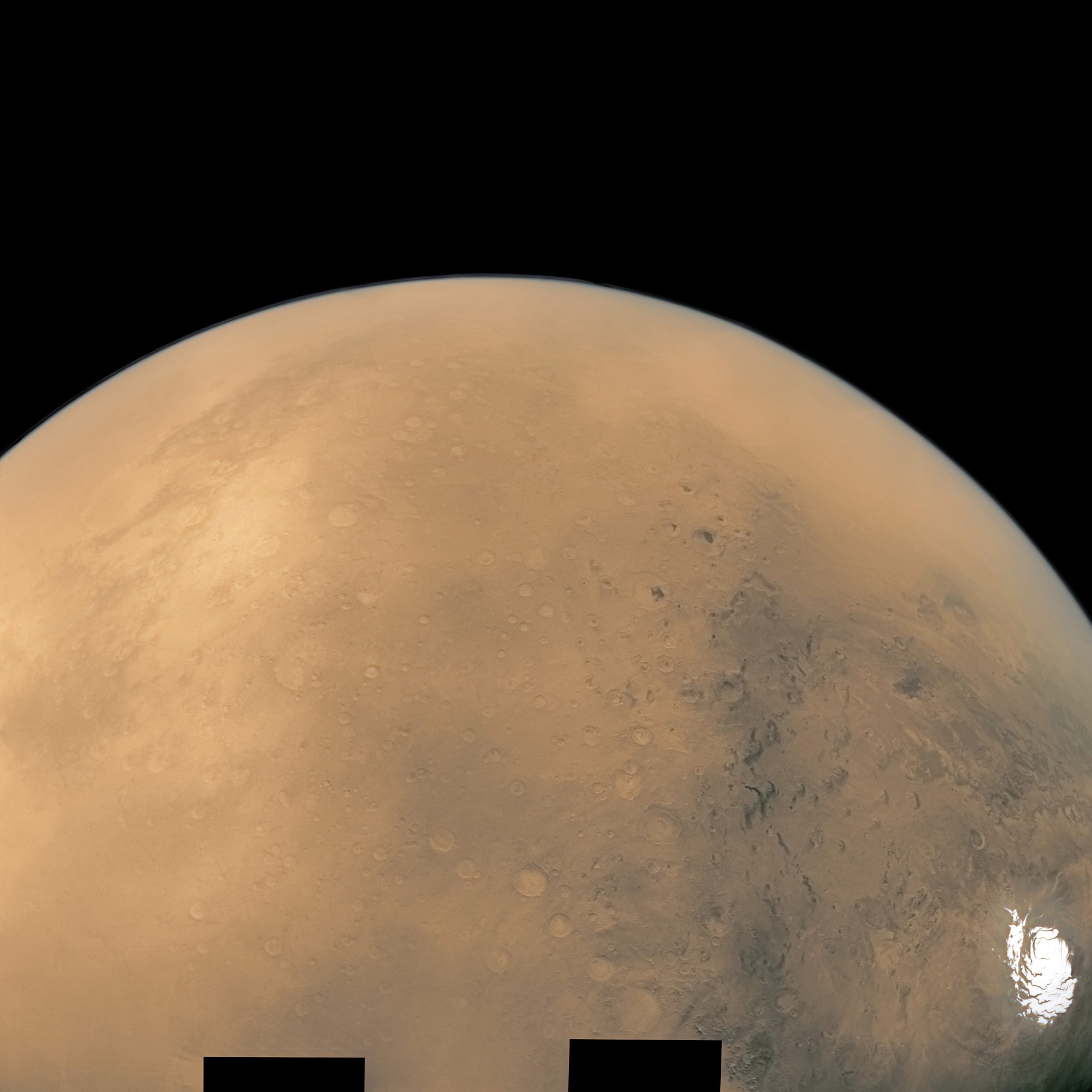

I am fond of the Viking missions. Their orbits took them far above Mars (as far as 56,000 kilometers from the surface), giving them the ability to take sweeping images of entire hemispheres. Modern missions mostly don’t stray so far from Mars’ surface, and can’t fully capture the same sweeping vistas captured by the Viking Orbiters. (Mars Express, which rises a little over 10,000 km from the surface at the highest point in its orbit, can come close, but only Mars Orbiter Mission occasionally gets full-disk views in high resolution.) Also, as reconnaissance spacecraft, the Viking orbiters were designed to study the broader weather and climatological patterns of the Martian atmosphere in a way that the close-up imaging provided by current missions can’t match.

In a way, Viking images are refreshing. They don’t show the topographies of a dead world, but a planet with active weather (even if that weather is tame in comparison to Earth’s). And so, I decided to work on bringing the images in Viking Orbiter Views of Mars into the digital age. I began with the raw data archived by NASA and used Photoshop to rescue some of the beautiful images from obscurity. After a few years of working with Viking imagery, it’s stunning to see how well the analog tube cameras still compare to the digital cameras that modern spacecraft are equipped with. Here’s some of what I’ve found:

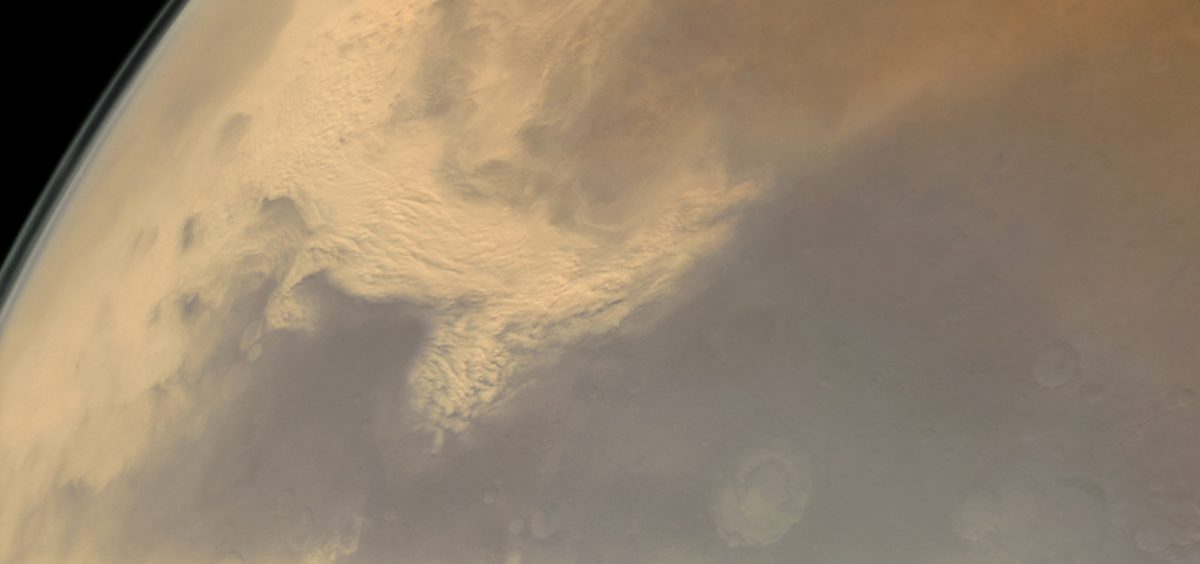

This is a lovely shot of the Tharsis Montes (Olympus Mons at upper left, and Ascraeus, Pavonis, and Arsia Mons from top to bottom, respectively, at lower right). This image, taken on June 24, 1978, captures Mars near its furthest point from the Sun. This period, known as aphelion, is accompanied by the formation of thick water ice clouds over the Tharsis region called the aphelion cloud belt. The tops of the mountains are in clear sky because they stand above most of the atmosphere. Their altitude influences the regional wind patterns, leading to standing waves in the clouds around Pavonis Mons, and the formation of lee clouds around the peaks of Ascraeus and Olympus Mons.

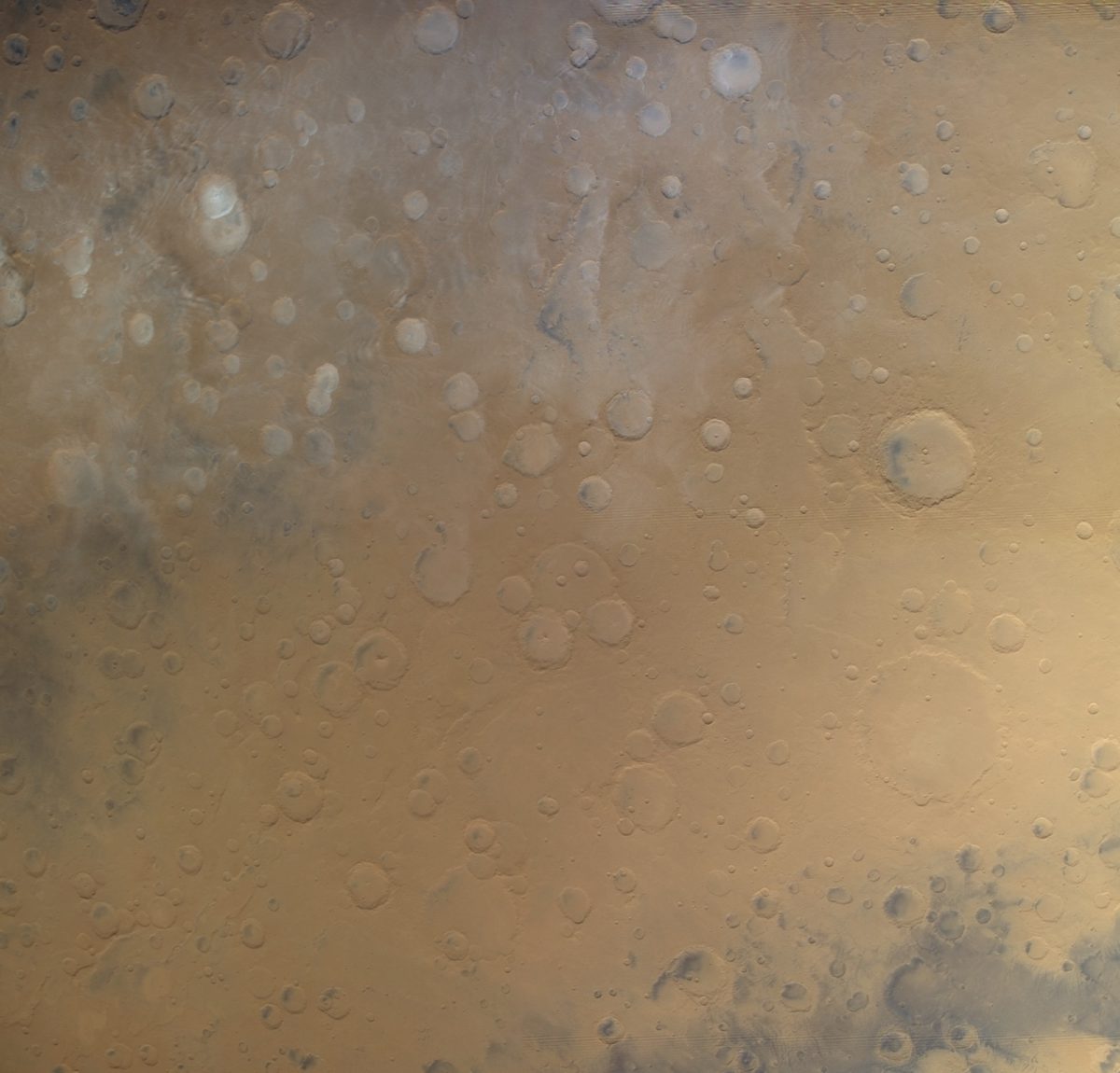

Here’s a shot of wispy cirrus clouds drifting over the Valles Marineris canyon system. This image, taken on September 29, 1979, was taken shortly after the beginning of northern spring. These water ice clouds are early harbingers of the aphelion cloud belt, which reaches its peak density in the northern mid-summer.

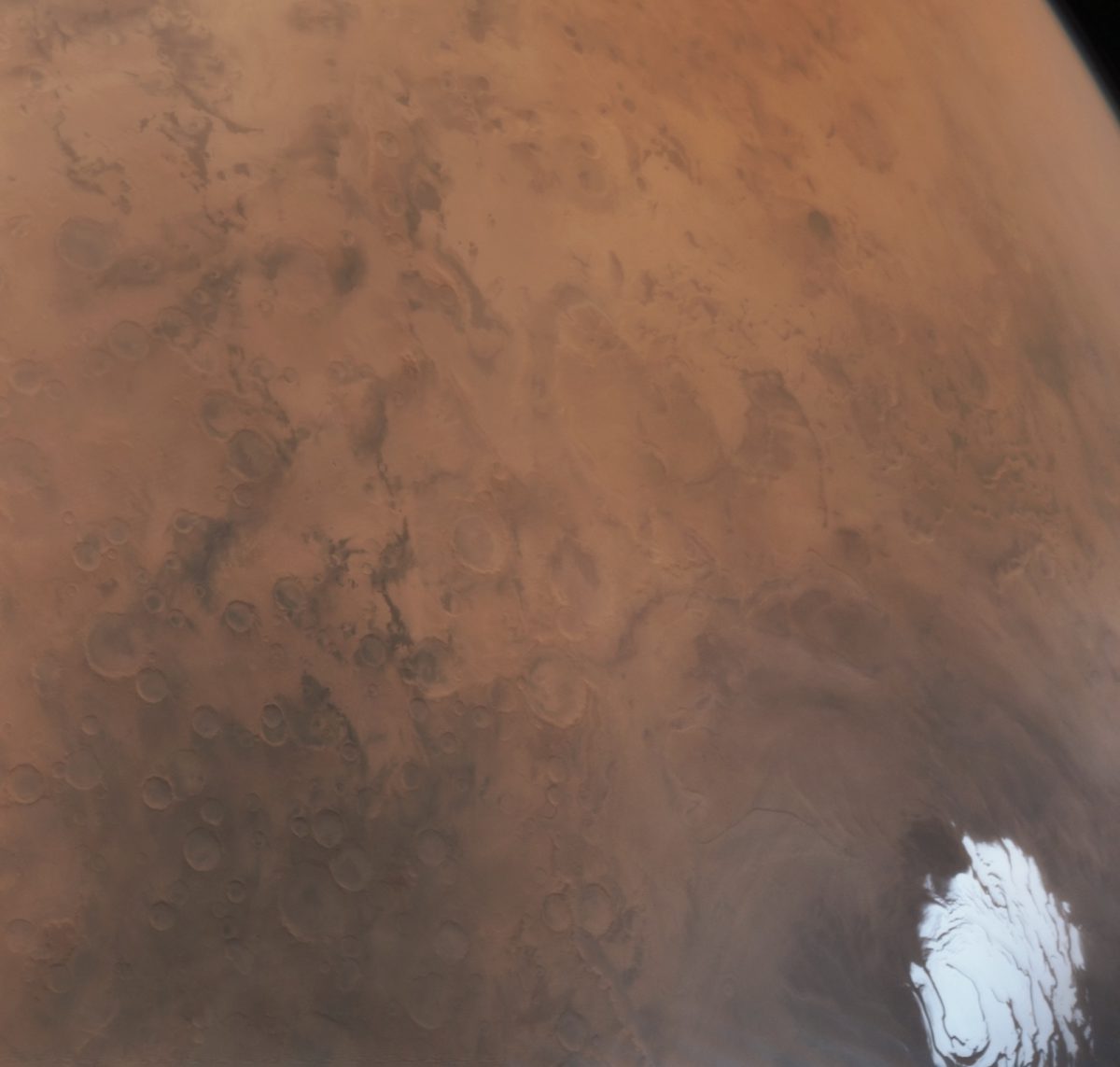

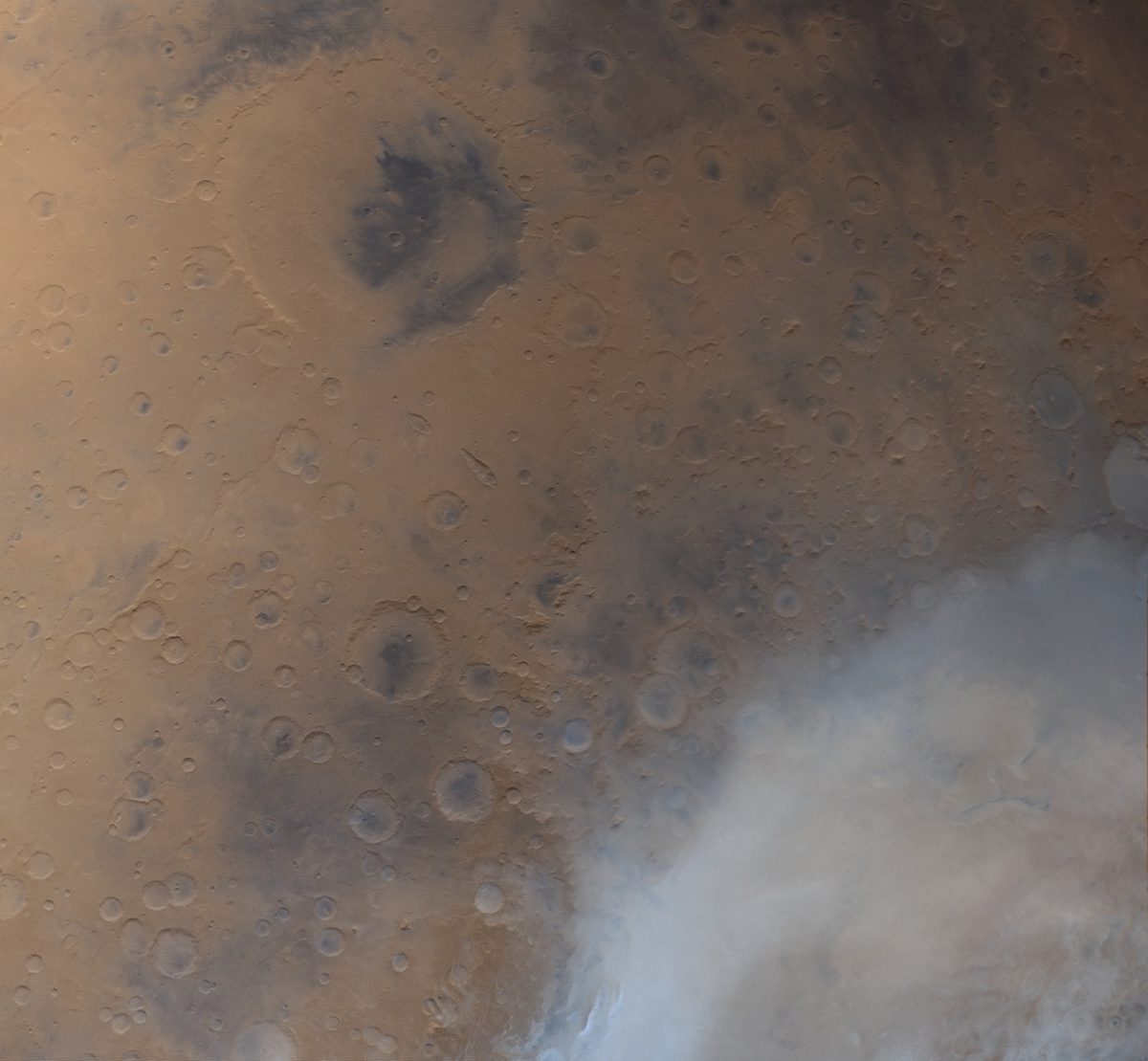

Dust storms are probably the most famous aspect of Martian weather, and for good reason. These storms frequently shroud the entire planet for months on end, and a storm in 2007 almost spelled the end for the Opportunity mission, which is still trucking along 11 years after its near-death experience! This image, taken on February 17, 1977, captures the beginning of one such global dust storm. The typical storm track for regional dust storms begins in the northern polar plains of Acidalia Planitia, dropping due south along the eastern edge of the Valles Marineris canyons. This storm is moving across the eastern edge of Thaumasia Planum, a region that makes or breaks a global dust storm. Most storms in this region peter out in this high, rugged terrain. Occasionally a storm, such as this one, will manage to survive the traverse and become turbocharged as it descends off the high plateau where Thaumasia Planum is located. Within days of this image, Mars was enshrouded in a thick dust cloud.

Viking also returned a few gorgeous regional images. They don’t show anything of particular interest, but I enjoy these image sets for their birds-eye view of the Martian surface.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth