Achim Vollhardt • Mar 28, 2014

Returning Explorers

Editor's note: Achim Vollhardt is one of the amateur radio operators who successfully contacted the returning ICE/ISEE-3 spacecraft. I asked him to tell his story about this achievement. --ESL

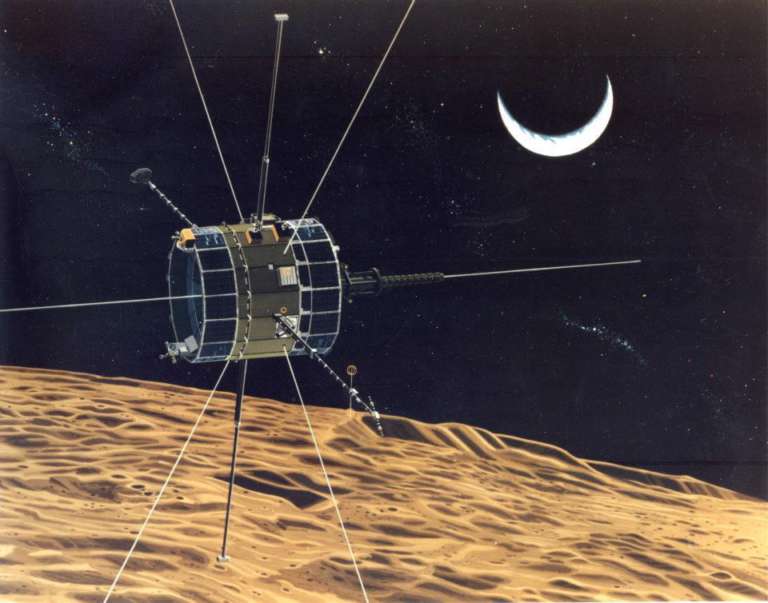

Imagine naval exploration, maybe 17th century. An exploratory vessel has left its home port a long time ago. While their scientific reports were groundbreaking and frequent in the beginning, the contacts became less over time, until the communication ceased altogether. The owner of the ship has no further interest in the ship, so all means of communications were dumped. People moved forward and a long time passed. However it was expected that the winds and currents will bring the ship eventually back to the vicinity of its home port.

Fast forward to 2014. The ship's name is ICE and it has been on a journey lasting over 30 years around our sun. While the owner has decided not to bring the ship back to its home port (in part because it does not know the ship's condition), a group of radio amateurs tries to find out how ICE is doing. Radio amateurs are individuals who spend their free time building transmitters, developing new means of radio communication, or simply having a chat with friends around the planet. Don't be fooled by the appearance of their equipment: while some parts look like treasures from 'Junkyard Wars', radio amateurs are highly creative in designing low-budget communication systems that are very close to, and sometimes exceed, commercial gear in terms of performance.

A small group of radio amateurs has been tracking interplanetary space probes since 2003. The motivation for this has its roots in another story which would justify a blog in itself. For now, it is sufficient to say that our group from AMSAT-DL (or AMSAT Germany) has been very successful in finding weak signals originating from far-away probes (like Voyager 1 in 2006) or detecting radar echos from other planets (like our Venus experiment in 2009). When we learned about ICE this was a challenge we just had to take.

The transmitter power of ICE is 5 watts. To put this into context, a GSM mobile phone transmits with 2 watts maximum. The problem now is the incredible distance these 5 watts need to travel, which currently (as of March 2014) is about 40 million km. This is a bit less than a third of the distance of the Earth to the Sun. Even at the speed of light, any radio signal from ICE takes 3 minutes to reach us.

Such a low transmitter power coupled with these distances require large antennas in order to concentrate the signal into the receiver. Think about a magnifying glass concentrating sunlight until it is powerful enough to light a matchstick. Our "magnifying glass" is such a concentrator, and it is a Junkyard treasure. The Bochum Observatory was built in the early 1960s and used for barely more than a decade. It was an industrial monument for close to 30 years until it was brought back into service by radio amateurs some 10 years ago. With its diameter of 20 meters, it is one of the largest radio telescopes worldwide that is under full-time control by radio amateurs. The surface for collection of radio waves is still fine today. The actual receivers were replaced with 21st-century cutting-edge hardware, which is performing very close to the limits of physics.

The mighty collection power of such a large telescope comes at a price: a very narrow field of view. Think about a spotting scope, which is very good at watching things at a distance, but searching an area with it is a very time-consuming task. Our telescope has a field of view that is about the apparent size of the moon. Finding ICE without prior knowledge of its approximate position in the sky would be hopeless. Fortunately, Jeremy Bauman from KinetX Aerospace was kind enough to provide us with a trajectory estimation based on the last tracking data from NASA, which dated back to 2008. We then knew where to look in the sky and thanks to documents on the internet, we also knew which frequency we had to tune in (similar to finding a particular radio station in your car).

March 1, 2014: Once all the hardware was wired together and the telescope repositioned to the estimated position, the data recording took place and modern digital signal processing could work its magic. This sounds very sophisticated but essentially is very similar to a PC soundcard and an algorithm called Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT). A particular way of presenting a long duration FFT analysis is the waterfall display, where the signal value of an FFT graph is coded with a color and displayed as a single line. If your setup now is producing one FFT analysis per second and your software is stacking these lines on top of each other as they are generated, the appearance of such a display is similar to a (very slow) waterfall, hence the name: waterfall display. The horizontal axis represents the frequency of a signal, and the vertical axis the received time (higher up is later).

So this is what we got out of 15 minutes of data:

What we see here is a curved line which means our frequency shifted down later in the recording session. It looks like an error but it actually is proof that the signal comes from ICE, as this frequency shift is an indication of relative movement between the signal source and the receiver. It is called Doppler shift and you can hear it as tone change when an ambulance is driving past you. What you also see is the gap in the signal for some minutes and again this is proof that the signal comes from ICE as we deliberately turned the telescope away by some degrees. If the signal had persisted, we would have determined it to be a locally-generated signal. Unfortunately we have plenty of those artificial signals, as the observatory is located in one of the most populated areas in central Europe (actually this was the very reason why the scientific radio astronomy stopped here in the 1970s).

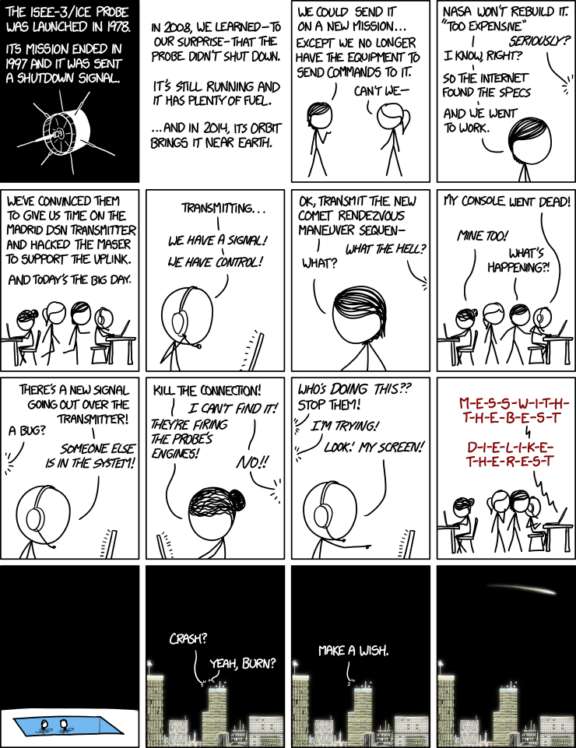

This was the time for the champagne. ICE is still around, its transmitter is working and so we can conclude that the power subsystem would also work. What next? xkcd nicely suggested that we can take over control and choose another comet at our discretion (or generate a nice shooting star for our beloved).

Reality is a bit more complicated: ICE transmits only an unmodulated carrier which (except for its power) does not give us any clues about the spacecraft’s health. And independent of any future plans, this would be the first thing needed to know: how are you? Switching on the modulation likely requires a simple command being sent to the spacecraft. Does somebody know this command? Probably yes. Can we send it to ICE? NASA has determined it can’t, which does not mean they technically can’t. Of course they could but in times of cutting down mission budgets like for SOFIA it would be hard to justify any expenses for a spacecraft way beyond its time. Can AMSAT-DL do it? Technically it is currently a ‘maybe’. We have demonstrated experience with high-power transmitters in our Venus radar echo experiment and we are confident we could generate a signal that is loud enough for ICE to respond to.

The current question is: are the people responsible for ICE (even today, somebody is) willing to cooperate with people donating their spare time for something with an uncertain future?

Or to come back to naval terms: Do we want to signal the approaching ship to tell us if the crew is still alive (the sensor packages are still working)? Do they still have fresh water (fuel) and are they fit enough to be sent on another journey?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth