Emily Martin • Dec 13, 2010

Boulders and Ponds on 433 Eros

Emily Martin is a former student of my former grad school officemate who is now a PhD student in the Terrestrial and Planetary Structural Geology and Geomechanics program at the University of Idaho. She is researching the fracture development on Enceladus, with an emphasis on strike-slip faults and crater-related fractures. This is her second guest post summarizing a recent paper in her field of study; her first was on Selk crater on Titan. I'm glad she found time to send another writeup! Anyone else out there care to give this exercise a try? Any professors want to assign this activity to your grad students? --ESL

There is really cool geology being explored on large, oddly shaped asteroids. The Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) mission (later renamed NEAR Shoemaker) reached 433 Eros in 2000, and one of the exciting results was the discovery of features called "ponds". 433 Eros is the only place in the solar system so far where they are found! I read about Eros' ponds in a paper called "Boulders and ponds on the Asteroid 433 Eros," by Andrew Dombard and three co-authors in the most recent Icarus.

I had to do some background research, because when I first picked up this paper, I was completely unfamiliar with 433 Eros. It was discovered by Carl Witt in 1898, and was the first near-Earth object to be discovered. Near-Earth, in the case of Eros, means an orbital distance that averages 1.45 astronomical units from the sun. 433 Eros was also the first near-Earth asteroid to be visited by spacecraft.

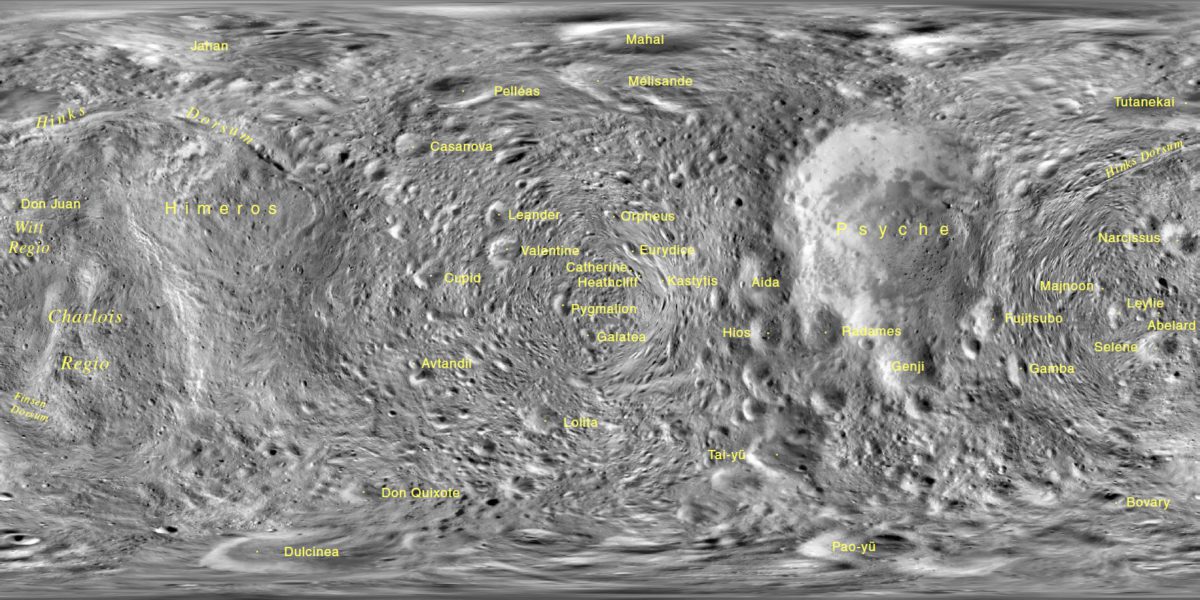

One difficulty with studying asteroids is trying to mosaic images together of a body that is so oddly shaped and project them on a flat surface. Spheres also don't project on a flat surface either, but there are a variety of map projections we use to change how we look at the images depending on what we are looking at.

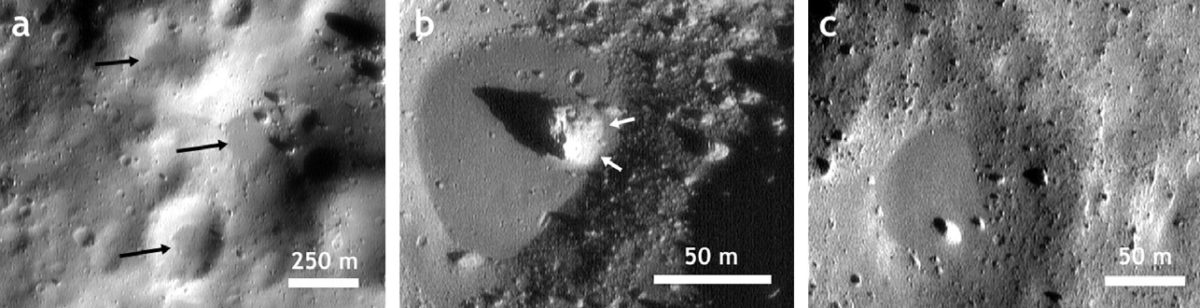

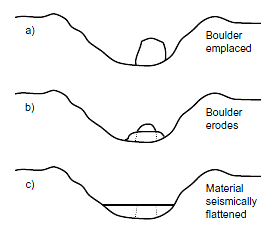

This paper is trying to understand how ponds form and how they are related to the boulders that are found inside them (I envisioned an egg in a bird's nest). "Ponds" are flat-floored depressions bound by sharp embayments, usually less than 60 meters across, but they can be as big as 210 meters across. "Boulders" are harder to define, because they are small and near the image resolution. They are identified as localized features with steep, positive topography, and usually have debris aprons skirting them.

Dombard and his co-authors created a model for how ponds and boulders form based on their observations. Ponds are found in places that get the most direct sunlight and are clustered around Eros' equator. Color images from the NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft showed that ponds were also slightly bluer than anything else. I've broken down their formation model into four stages:

This is where it becomes really important to know that 433 Eros is an S-type asteroid -- which is where we think stony meteorites come from. Ponds and boulders are mostly found in the hottest places on 433 Eros, but these places also get very cold when they are not receiving sunlight, just like the airless Moon. The result is extreme temperature changes creating microscopic cracks that get bigger in high stress environments.

Where does the stress come from? When something gets hot, it expands. When surface layers of the boulders are warmed by the sun during the daytime, chondrules (small mineral grains) within the boulder get squeezed by the heat-driven expansion. The opposite will happen during periods of nighttime, colder temperatures. After many hot and cold cycles, the outer layer of the boulder is weakened enough to fall off at a rate of about 1 meter of boulder material every 10-100 million years. The erosion rate -- which is short compared to the age of the solar system, but still a reasonably long period in the geologic lifetime of an asteroid -- can also explain why there are some ponds that do not have boulders in them.

I already mentioned that so far, ponds have only been found on 433 Eros. Dawn will visit two much larger asteroids, Vesta and Ceres. Will it find ponds there? Dombard and his co-authors suspect Ceres is too icy for ponds to exist, and if they occur on Vesta, they will be much larger. I will now be paying very close attention to images coming back from Dawn when it arrives at Vesta next summer!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth