Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 18, 2017

#AGU17: JunoCam science

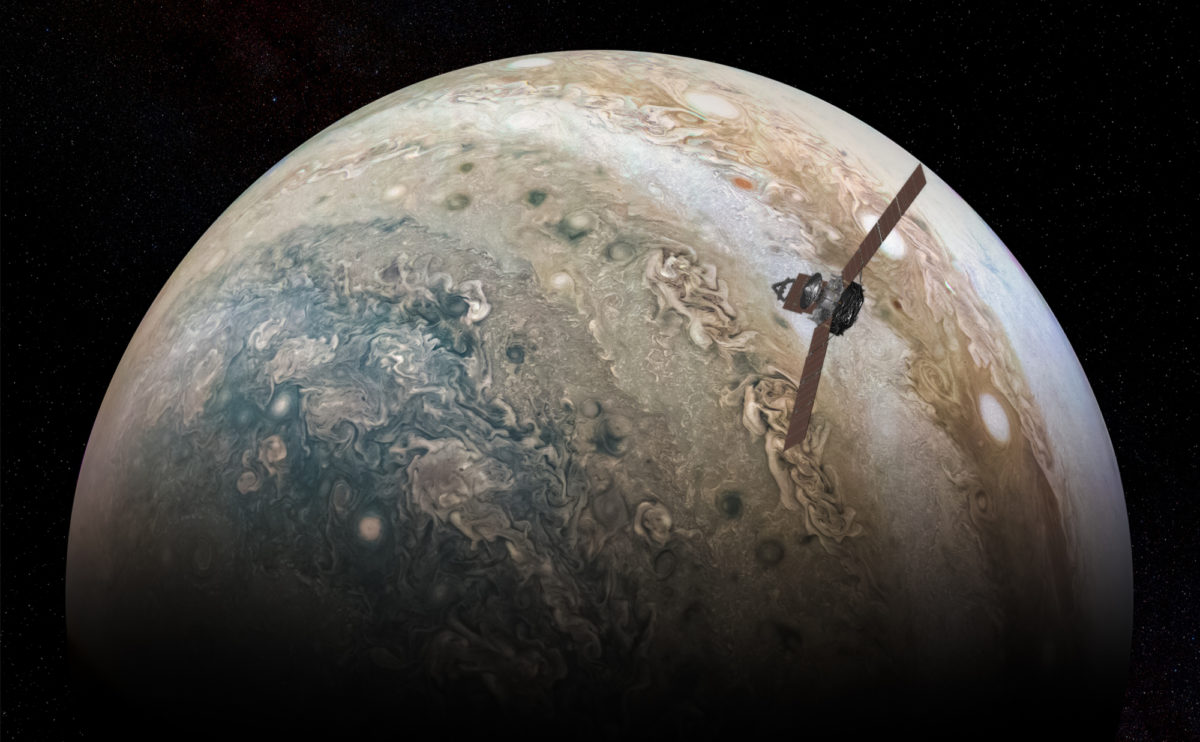

JunoCam has been wowing us with gorgeous images of Jupiter since Juno arrived. That's its entire reason for existence: the fact that it would've been criminal not to send a camera on a Jupiter mission, even though the camera wasn't required to achieve Juno's interior-focused science objectives. Time and again, though, small cameras have yielded unexpected scientific discoveries. At last week's American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting, JunoCam team leader Candy Hansen gave the first public presentation focused on the science achieved by JunoCam, and asked the gathered scientific community to join in.

Candy kindly shared her presentation with me so I can summarize it thoroughly here. The first and most obvious results came from JunoCam's spectacular images of Jupiter's poles. After all, JunoCam was explicitly designed to have a field of view able to encompass all of Jupiter's disk at the moment on each orbit that Juno passes above and below each pole. There are gorgeous swirling storms all over both poles. Candy showed that citizen scientists have documented the flow direction in these storms and found it to be cyclonic (anticlockwise in the northern hemisphere, clockwise in the southern hemisphere).

Both poles have a circle of cyclones surrounding the pole, but there is a different number of cyclones in each pole. The north pole has eight, so they form an octagon, but Candy points out that they alternate in latitude, so she characterizes it as two squares. (I've just recorded this week's Planetary Radio with Mat Kaplan, and together we decided that this is a circumpolar conga line of storms sticking their legs out to alternate sides.) It's not possible to see whether there is another cyclone right at the pole in JunoCam data because it's northern polar winter on Jupiter. Of course, it's entirely possible for the thermal imager JIRAM to see whether there is another one at the pole, and in fact I saw a JIRAM image of the beautiful cloud structure at the poles during the AGU talks, but I do not remember whether there was a storm at the center visible to JIRAM. (Argh!)

In the south, there are five circumpolar cyclones, making a squashed pentagon (pentacle? This is a different kind of dance entirely from the northern conga line!) A gap in the circle of cyclones makes it seem as though it ought to have a sixth -- it's closer to a "home plate" than a regular pentagon. Candy remarked that they've been watching to see if one of the other smaller storms in the area will scoot in to fill the gap and turn it into a hexagon, but so far, that hasn't happened.

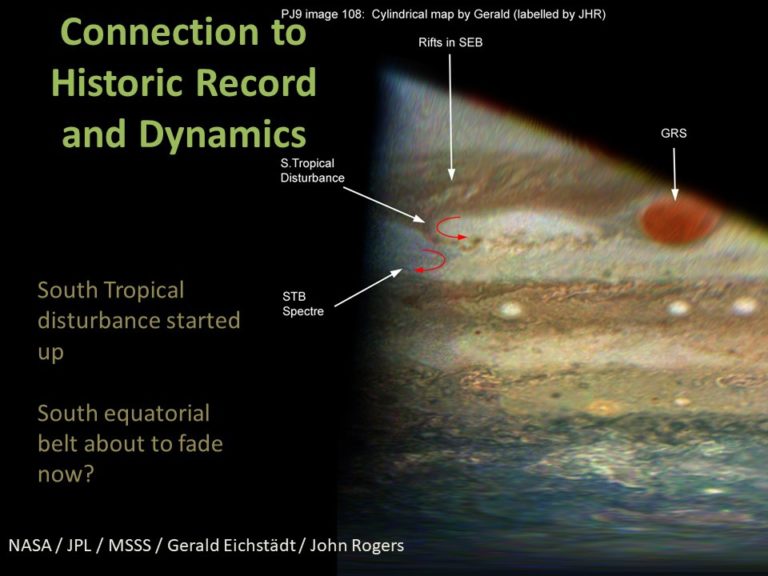

One of the citizen scientists leading the effort to interpret JunoCam images is John Rogers of the British Astronomical Association. He's been comparing the JunoCam images to historical photos of Jupiter, and noticed signs that Jupiter's south equatorial belt may be getting ready to fade again, as it last did in 2010.

Candy also shared this awesome gif showing cyclonic rotation in the south temperate belt "ghost" (so named because it's a storm that is specter-like; with the same color as its belt you hardly see it except by its motion).

Members of the public don't often play with the methane-filter data from JunoCam, but it reveals interesting features in Jupiter's clouds, notably a wavy-edged south polar hood that is bright in the methane band.

Higher-resolution JunoCam images reveal mindblowing detail in the clouds, including all these (relatively speaking) itty bitty "pop-up" storms in the south tropical zone. You can tell they pop up above the rest of the clouds because they cast shadows toward the terminator (toward the right of the image).

Cross-checking with other instruments, Candy said they were not thunderheads, because there is no evidence for lightning under these clouds. Instead, they may be altocumulus castellanus:

JunoCam's color-vision capability raises more questions than it answers. Candy pointed out that most of the images in her talk had dramatically enhanced color. She mentioned Bjorn Jonsson's work producing versions intended to show how a human would see the clouds. It's less dramatic, certainly, but she told me later that when she looks hard at Bjorn's versions, she sees all the same differences you can see in Sean Doran's -- they're just more subtle in the natural-color images.

Candy commented that the color of the clouds "is as intriguing as can be." She pointed out that adjacent storms can have different colors -- one brown, one blue. They can have different-looking structures. They can have different-colored rims and centers. "So much to work on here." Yes.

Clearly, there's a lot of science to be done with JunoCam images. But JunoCam doesn't have a science team per se -- there are scientists involved, like Candy and Glenn Orton and others -- but their roles are to plan the images; there's no funding to actually do the science. In any case, it would be inconsistent with the philosophy of JunoCam to keep the science fun for themselves. So Candy announced a new page on the JunoCam website, the Analysis page, and invited everybody in the room at AGU to participate and to spread the word.

"The goal of it is to do science in a fishbowl," Candy said. "We want to do all of the science analysis in the public eye, to give the public a chance to watch the sausage being made." While she was addressing a room full of scientists, and hoping to entice scientists' interest in the work, it was clear from her presentation that skilled and devoted amateurs like John Rogers and Gerald and Bjorn and Sean would be part of the effort, too.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth