Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 18, 2015

Curiosity stories from AGU: The fortuitous find of a puzzling mineral on Mars, and a gap in Gale's history

Yesterday at the American Geophysical Union meeting, the Curiosity science team announced the discovery of a mineral never before found on Mars. The finding was the result of a fortuitous series of events, but as long as Curiosity's instruments continue to function well, it's the kind of discovery that Curiosity should now be able to repeat.

The mineral in question is tridymite, a flavor of quartz that forms under low pressures and very high temperatures. On Earth, it's found near volcanoes. Curiosity found it with a CheMin analysis of a sample drilled at a site called Buckskin. How exactly the tridymite got there is a puzzle that is yet to be solved; as far as mineralogists know, there's no way that scientist currently know of to make it under the kinds of conditions that prevailed in the ancient lake environment in which the Murray formation was laid down. Either Mars can make tridymite in a way that Earth doesn't, or (more likely) the tridymite was carried there from some other location. But even that doesn't solve the riddle, since the kinds of environments in which tridymite gets made on Earth are not found on Mars.

The story of the silica and why it's a puzzle is well told in the Curiosity press release and in this article by Kenneth Chang, but the story of how Curiosity made this discovery is a fun one, too. It happened last summer, right around sol 1000, in Marias pass.

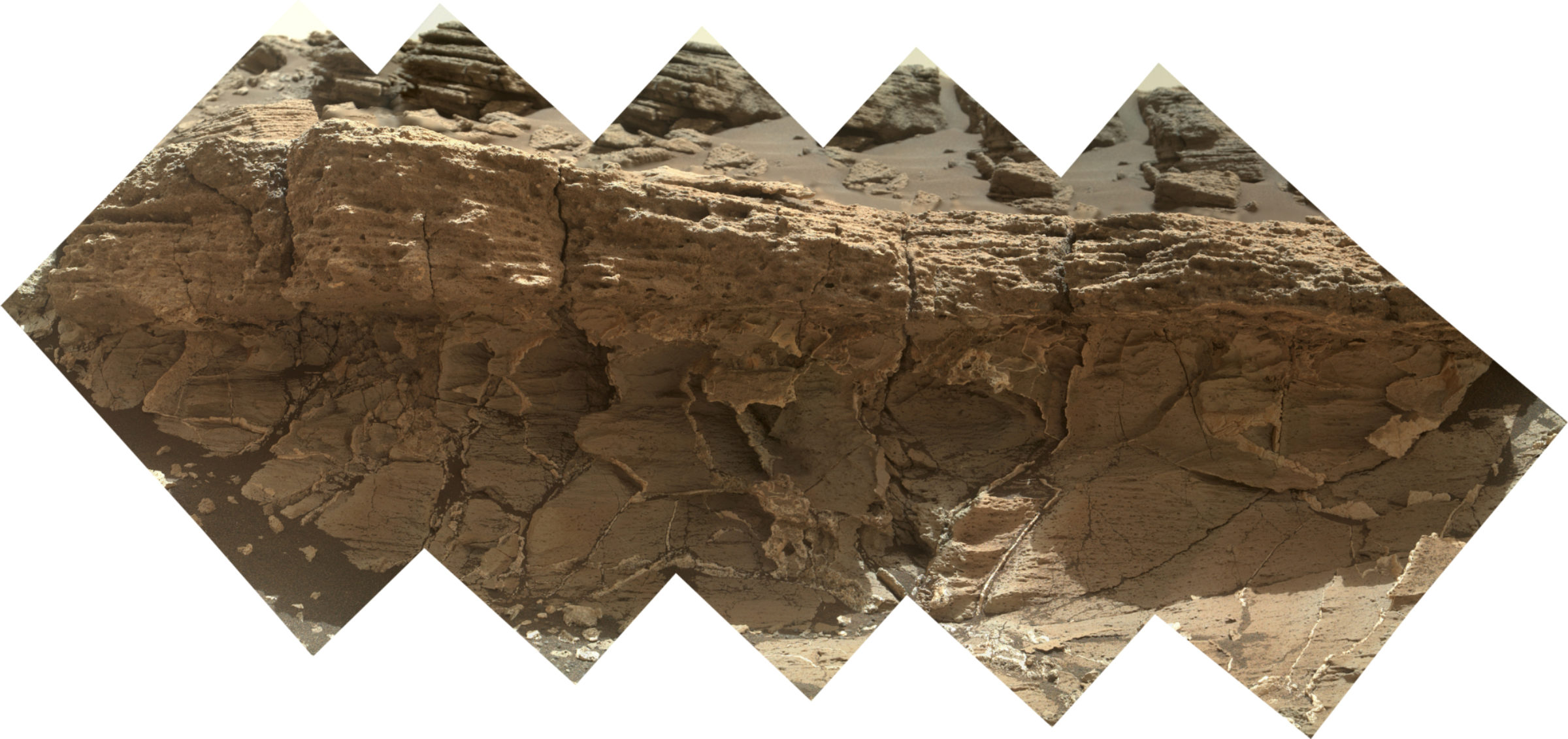

This view from the Mast Camera (Mastcam) on NASA's Curiosity Mars rover shows the "Marias Pass" area where a lower and older geologic unit of mudstone—the pale zone in the center of the image—lies in contact with an overlying geologic unit of sandstone. This scene combines several images taken on sol 992 (May 22, 2015) of Curiosity's work on Mars. The scene is presented with a color adjustment that approximates white balancing, to resemble how the rocks and sand would appear under daytime lighting conditions on Earth.

Image: NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSSAt that time, Curiosity had driven onward from the first Mount Sharp science site (Pahrump Hills), where the rover had drilled several times into the lakebed mudstones known as the Murray formation. Having spent a long time at Pahrump Hills, the mission was eager to make driving progress toward the next-higher rock unit, called the Stimson formation. Stimson is more resistant to erosion than Murray, so it tends to cap hills, and the team was having a tough time finding a safe route up onto it. At the same time, the scientists wanted to find a good spot where they could see Murray and Stimson directly in contact, so that they could try to figure out the relationship between the two different kinds of rock. And they were under time pressure, because conjunction was approaching, when the mission would have to stand down operations to wait for Mars to pass behind the Sun as viewed from Earth. Conjunction lasted from sol 1004 through sol 1026.

While all of this was happening, various science and engineering teams were getting close to solving some problems on the rover. There had been a scary short circuit on the drill on sol 911, but the engineers were almost ready to declare it back in action. The ChemCam instrument (which uses a laser to vaporize rock and study the colors of the glowing plasma to determine rock elemental composition) had been functioning without the ability to autofocus since early on in the Pahrump hills campaign, but they finally developed and implemented a workaround for that on sol 989.

Meanwhile, in a completely independent effort, the ChemCam team had been developing a new and more precise calibration for their instrument. ChemCam isn't a tricorder; you can't just shoot a rock with a laser and read elemental composition off a screen. (Unfortunately.) Transforming ChemCam readings into elemental abundances requires comparing the data we get from Mars with ChemCam measurements of rock samples of known composition measured on Earth. When the rover landed on Mars, the ChemCam calibration model was based on a library of 66 rock samples that they'd shot with the actual ChemCam instrument that is now operating on the Martian surface. Since landing, they've built a lab containing a ChemCam copy that they can operate under Martian conditions, and they developed a new version of their model that incorporates 450 different kinds of rocks, coving a much wider range of compositions than the first 66.

Applying the new calibration to ChemCam data changes the results that they report from Mars. By email, ChemCam principal investigator Roger Wiens told me: "These changes are relatively minor for compositions close to the average Mars crustal composition (e.g., soil, dust, Sheepbed mudstone). The largest changes are for compositions that are far from the average Mars crust (calcium sulfate veins, feldspars, etc)." (Papers have not yet been published on the new calibration, but they are forthcoming from Sam Clegg, Ryan Anderson, and Olivier Forni.)

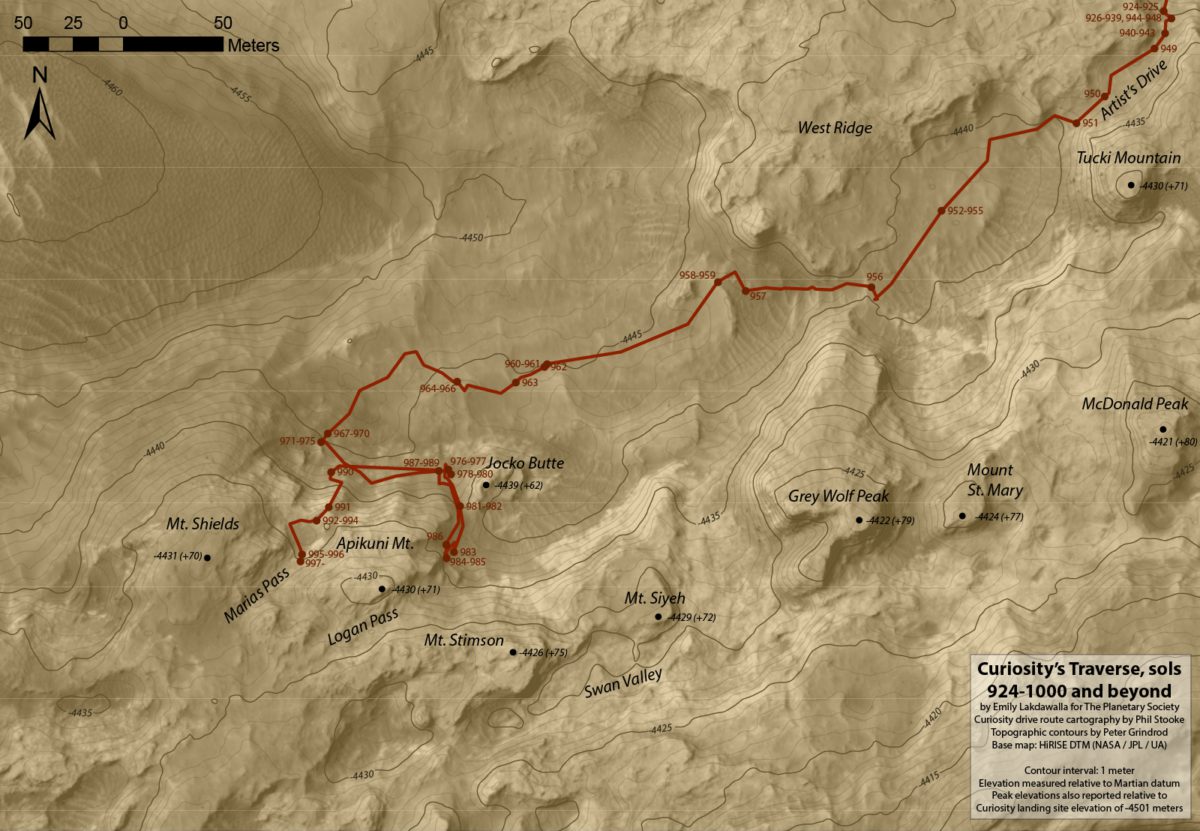

Right before conjunction, the team had given up on finding a way to drive through a spot called Logan Pass onto the Stimson, and had driven up into Marias pass, where they took the pretty panorama I show at the top of this post. Here's a map showing the rover's route as of conjunction:

With conjunction lasting several weeks, the team took the opportunity to get together for a July science team meeting in Paris. At that meeting, one of the science instruments, DAN (Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons), reported seeing something strange: an unusually high reading of neutrons in a spot that the rover had passed over back on sol 991, several drives ago. The DAN team usually interprets high neutron counts to mean high abundance of hydrogen in the soil.

Then the ChemCam team gave a presentation on their recalibration effort. They had not been using it for operations yet, but had been "beta-testing" it on the first ChemCam analyses that they'd done since getting autofocus back online, on sol 989. Lo and behold, a few of the spectra from their beta-testing effort showed something really surprising: a huge abundance of silica. Those ChemCam readings had been taken at the same spot that the DAN team had found the high neutron readings. Neither team had known of the other's anomalous measurements until the presentations at the Paris team meeting.

Either one of those two things -- the high neutrons or high silica -- wouldn't have been enough to make the team turn the rover around, but taken together, they showed that the rover had passed over a truly unusual rock. Moreover, the engineering team gave the scientists permission to use the drill again. So after conjunction was over, the team decided to command Curiosity to retrace its steps to the northeast, back to the high-silica, high-neutron region, looking for a spot to drill.

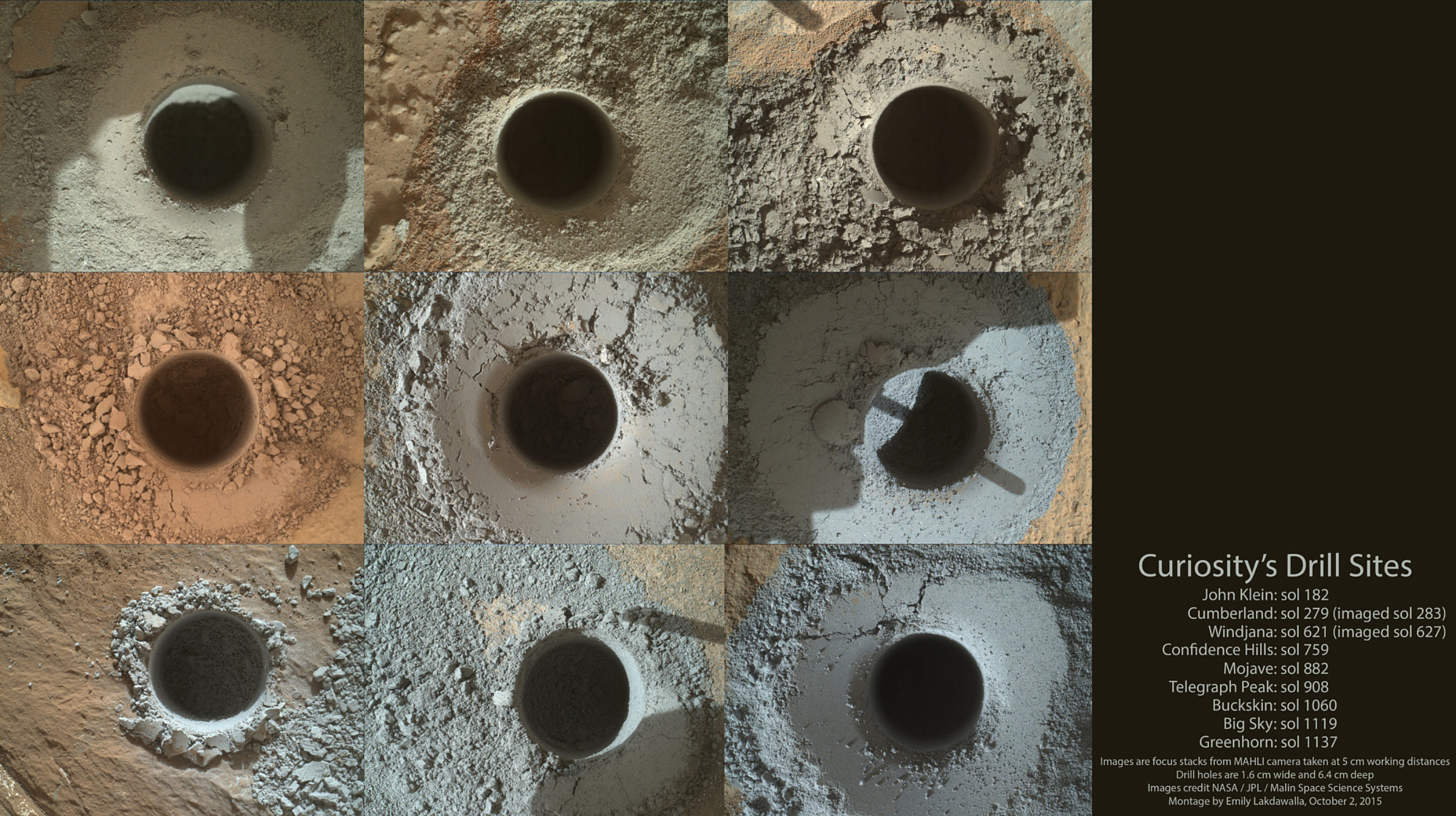

It was hard to find a good drill site, and the rover wound up driving back and forth a couple more times before finally locating a good spot, at a site called Buckskin. They drilled, and found the drill tailings to be brighter than anything they'd seen before or since (according to a poster presented at AGU by Mastcam team member Danika Wellington).

CheMin found it to be full of tridymite.

The graph at right presents information from the Curiosity rover's onboard analysis of rock powder drilled from the "Buckskin" target location, shown at left. X-ray diffraction analysis of the Buckskin sample inside the rover's Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument revealed the presence of a silica-containing mineral named tridymite. This is the first detection of tridymite on Mars. Peaks in the X-ray diffraction pattern are from minerals in the sample, and every mineral has a diagnostic set of peaks that allows identification. The image of Buckskin at left was taken by the rover's Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera on July 30, 2015.Image: NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

The DAN team realized that the high neutron counts they observed were not strictly from an enhancement of hydrogen. The neutrons that DAN sees are relatively slow-moving (low-energy) ones that have had their energy reduced by interactions with atoms in the rocks beneath the rover. Neutrons can collide with hydrogen atoms, which very effectively decreases their energy in the process, but they also can be absorbed by iron, chlorine, and other atoms. The high silica rocks at Marias pass had a markedly lower abundance of absorbing atoms, increasing the number of observed neutron counts, which is partly what DAN was seeing in their data.

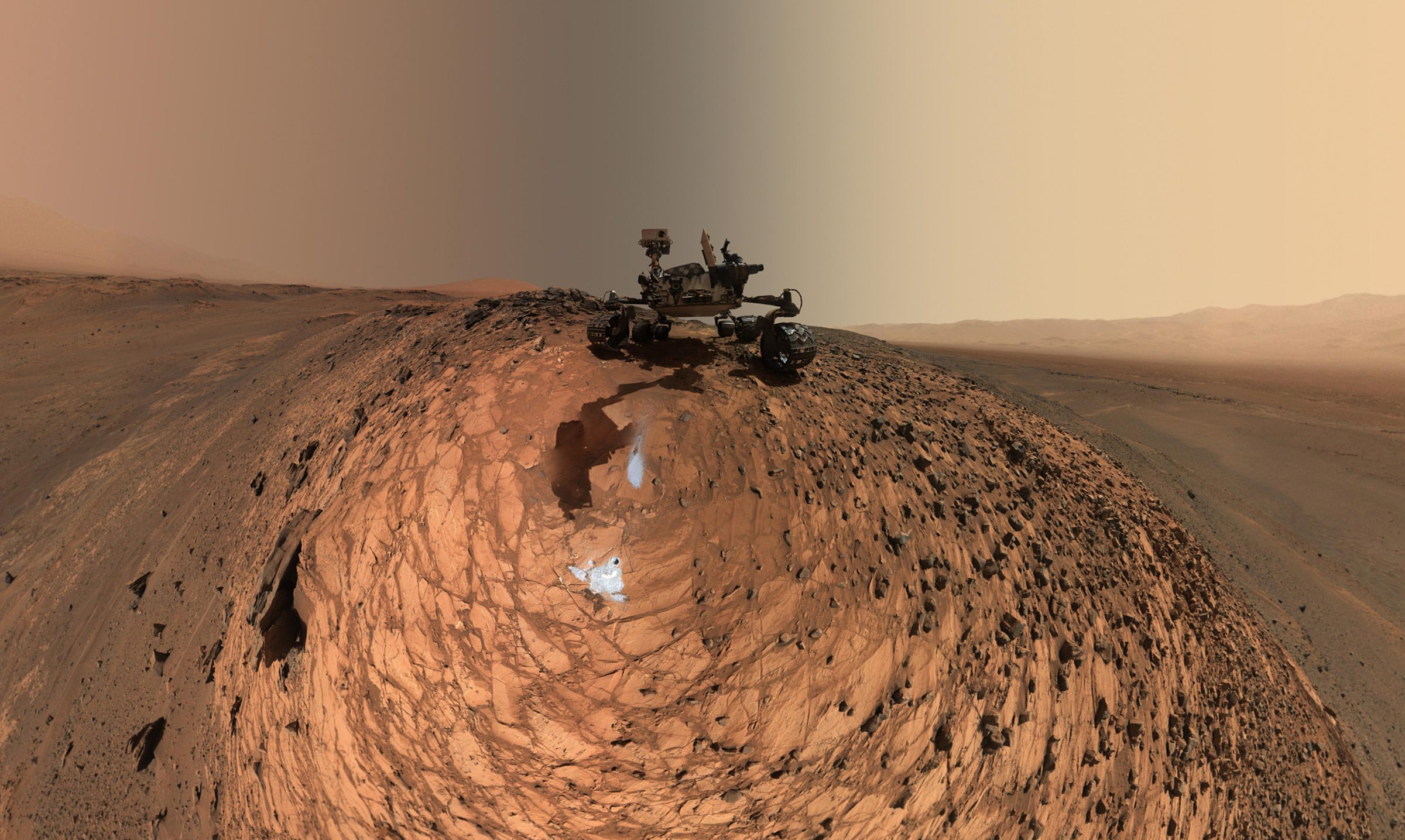

So Marias Pass was a fascinating spot, and the tridymite a cool (if very puzzling) find. They wrapped up work at Buckskin with a fun self-portrait, and drove on up into the Stimson.

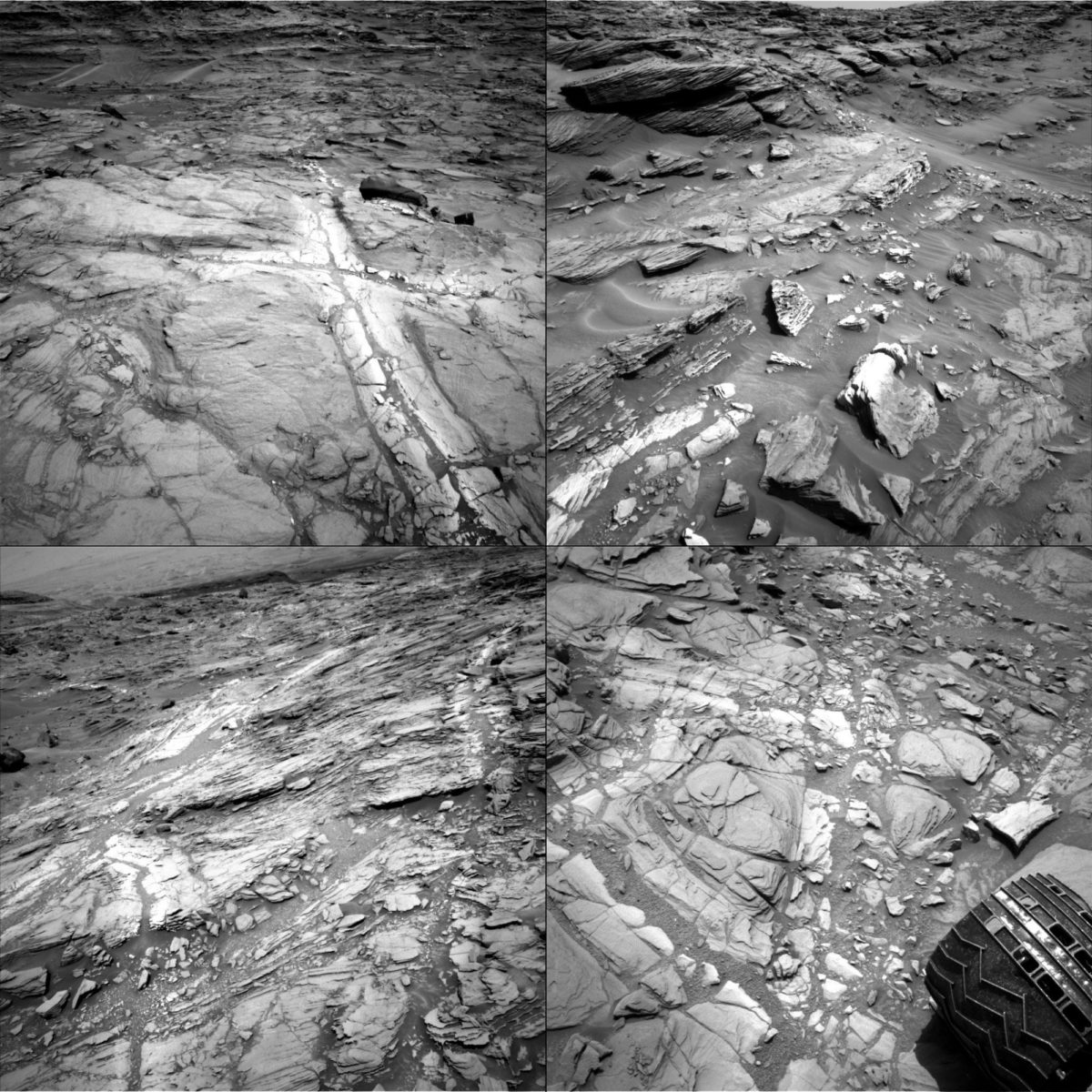

There they were on the Stimson, with a new energy: allowed to drill again, and equipped with a ChemCam instrument that was fully operational for the first time in nearly a year -- in fact, better-operating than before, thanks to the recalibration that allowed them to spot more anomalous rock compositions. Driving across the "washboard" ridges of the Stimson, they found weird haloes surrounding fractures in the rock.

Now, Curiosity has seen bright, white calcium sulfate veins in every kind of rock it has explored to date. But these haloes are not calcium sulfate veins. The calcium sulfate veins are places where an opening in the rock was filled by the deposition of a new mineral. The haloes seemed to be some kind of alteration of rock in place, not the deposition of something new. With the newly capable ChemCam, they were able to zap haloes all over the place, and found that the haloes marked rocks that were enriched in silica relative to the rock away from the haloes. Huh.

This view from the Mastcam on NASA's Curiosity rover covers an area in "Bridger Basin" that includes the locations where the rover drilled a target called "Big Sky" on sol 1119 (Sept. 29, 2015) and a target called "Greenhorn" on sol 1137 (Oct. 18, 2015). Color-coded dots represent the amount of silica in targets examined by the ChemCam instrument. A key on the right shows the percentage of silica (SiO2), by weight, corresponding to the color-coding. Enrichment in silica clearly corresponds to the fracture zones.

The scene combines portions of several observations taken from sols 1112 to 1126 (Sept. 22 to Oct. 6, 2015) while Curiosity was stationed at Big Sky drilling site. The Big Sky drill hole is visible in the lower part of the scene. The Greenhorn target, in a pale fracture zone near the center of the image, had not yet been drilled when the component images were taken. Researchers selected this pair of drilling sites to investigate the nature of silica enrichment in the fracture zones of the area.

Image: NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSSThe team debated what that might mean. Was the silica enrichment a result of silica-rich stuff being deposited in the rocks by groundwater? Or was it a place where the other stuff was being leached away? The latter hypothesis was favored by readings from the Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer, which showed that wherever there was an enrichment in silicon, there was also an enrichment in titanium. Spirit's APXS had also observed something similar in rocks near Home Plate. Titanium doesn't dissolve readily in water, so if you leached elements out of a rock, it's an element that would be left behind.

As a general comparison with these selected high-silica targets in Gale Crater, the gray dots in the graph show the range of titanium and silicon concentrations in all Martian targets analyzed by APXS instruments on three Mars rovers at three different areas of Mars.Image: NASA / JPL / University of Guelph

The team decided the best way to answer this question would be to drill. In fact, they needed to drill twice: once in the Stimson unit far away from a fracture, and once within a halo, close to a fracture. Comparing Big Sky (ordinary Stimson) to Greenhorn (halo Stimson), they found Greenhorn to have abundant opal, another form of silica. Unfortunately opal can form in a wide variety of different environments, so its presence doesn't tell us anything about whether it was a hot, acid or temperate, neutral environment when the water was flowing through the rocks, so the jury is still out on that decision. Either way, water was required.

How does the silica in the haloes in the Stimson unit relate to the tridymite in the Murray formation that the rover saw at Marias pass? There may or may not be any relationship. I got one Curiosity team geologist to speculate that the opal in the Stimson haloes was carried there in water that had flowed through the tridymite-rich Murray formation, but there's really no way to confirm or disprove that hypothesis that I know of.

And now for the other Curiosity story out of AGU. Studying the silica is not the only science experiment that Curiosity was conducting while passing through Marias pass. The other reason they drove back and forth so many times was to find a location where they could see Murray and Stimson directly in contact with each other. They found that at a spot called Missoula, capturing this gorgeous MAHLI panorama.

You can see a lot of calcium sulfate veins in the lower, Murray formation rock, which are truncated by the overlying Stimson rock. That alone isn't enough to be sure that Murray and Stimson formed at very separate times; it could just be that the Murray formation has different properties to the Stimson that allow veins to propagate easier in it than in the Stimson. But there's something peculiar about the Stimson unit where it contacts the Murray; it's full of little rock fragments, whereas higher in the section it's a much more uniform fine-grained sandstone. (Enlarge the MAHLI photo above to spot those grains.) The newly capable ChemCam shot at the Stimson unit right above the contact, profiling the composition across matrix and grains. And when ChemCam struck a particularly bright grain, one team member told me, "Bam! Calcium sulfate."

What does it mean for tiny little grains of calcium sulfate to be incorporated into the base of the Stimson? It means that before the sands of the Stimson were laid down, the Murray formation had already been buried and turned into rock. The Murray rock had already been shot through with calcium sulfate veins. Then it had already been unburied and exposed at the surface, where the calcium sulfate veins had eroded away into calcium sulfate pebbles. When the Stimson sands blew through, the bottom-most sand layers incorporated broken up bits of Murray. In other words, a whole lot of time passed between the Murray and the Stimson. Millions of years. Maybe tens or hundreds of millions.

Kevin Lewis presented a poster at AGU that argued for the Stimson being the youngest rock that Curiosity has encountered. As Curiosity has driven along, it has found the elevation of the base of the Stimson to march up the mountain; the base of the Stimson unit tilts about 4 degrees to the northwest. It's not an originally flat-lying rock that has been tilted, he argued; rather, the topography of a central mountain in Gale crater was already present when the Stimson sands were draped across its northern flanks. They looked at the direction of the crossbeds, and determined that the flow of wind or water that laid down the Stimson sands was moving from west-southwest to east-northeast -- which is to say, basically across the slope. That, in turn, means that the fluid that transported the Stimson sands was almost certainly not water (at least, not most of the time); they're windblown sands, much like the modern Bagnold dunes. Except they don't contain olivine. And they're blowing in a different direction. And nobody knows what causes the topographic expression of east-west trending ridges in the Stimson. So perhaps they're not at all like the Bagnold dunes! As Curiosity keeps driving, Lewis told me, it will be able to investigate isolated outcrops of Stimson that the rover can drive around and view from all sides, which should help the team understand its depositional environment a little better.

It's a pleasure to see the rover using all its instruments together, as intended, on the rocks that the rover was sent to Mars to study. Getting ChemCam back to full function, with the new-and-improved calibration, has been particularly helpful. It took a long time to get going, but the science mission is really underway now.

Curiosity is now exploring the modern sands of Bagnold dunes, and will continue to do that for several weeks. I'll post a writeup of that campaign after the holidays.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth