Emily Lakdawalla • Mar 19, 2015

LPSC 2015: First results from Dawn at Ceres: provisional place names and possible plumes

Three talks on Tuesday at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference concerned the first results from Dawn at Ceres. Dawn has only just entered orbit around the largest asteroid, and the spacecraft is currently on its night side. You've already seen in my blog many of the best images that we have so far. So it's early days yet for Ceres science, but what Dawn has seen so far is pretty exciting. As a reminder, here is a series of images that shows how Dawn's point of view on Ceres has changed throughout its approach to orbit insertion:

And here's a look at the world rotating:

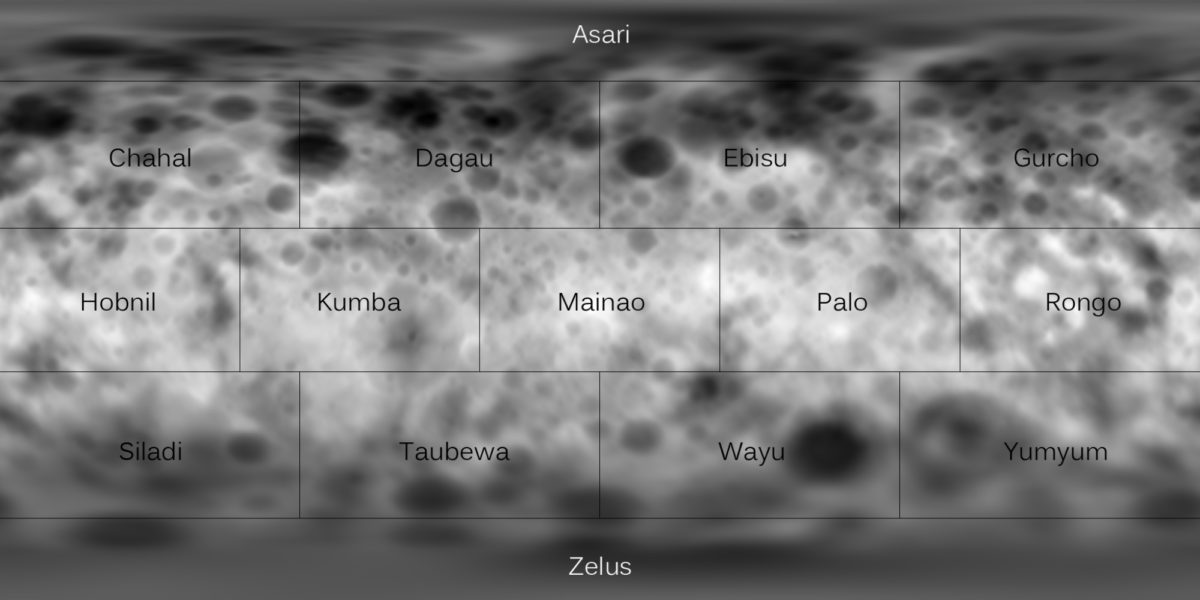

And here is a newly released digital elevation model for Ceres, available from the Planetary Data System:

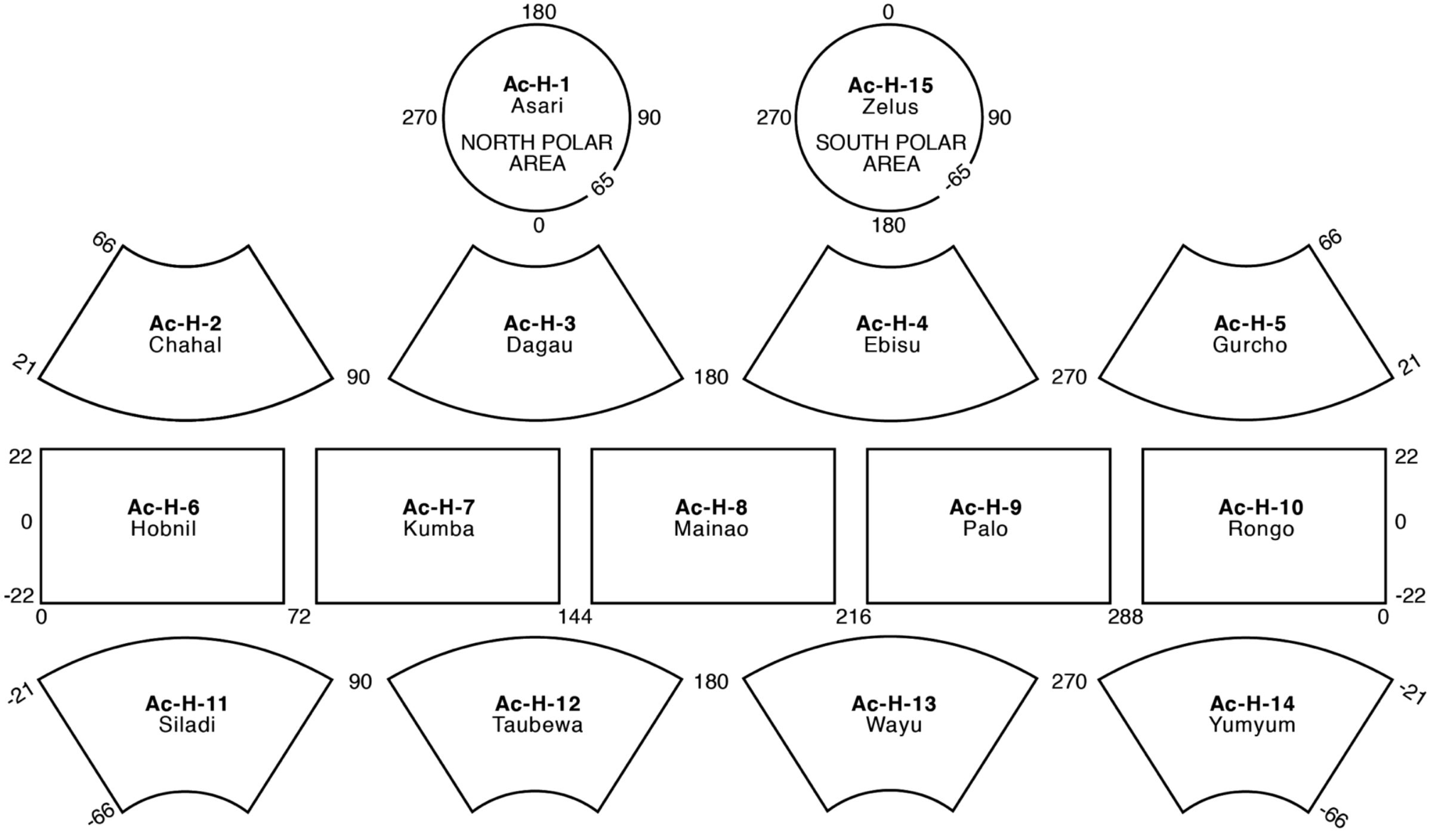

As you can see, Dawn has already observed the entire globe of Ceres, albeit at low resolution. Chris Russell opened the session with an overview of the mission and some early first impressions of Ceres. "This is very much unlike Vesta," he said. The impact craters are quite different. In general, Russell said in response to an audience question, early Dawn measurements of Ceres' shape and physical properties are results are "almost perfectly consistent" with the work done by Peter Thomas and coworkers on Ceres' shape as seen in Hubble images. The major news from Russell's presentation was the announcement of some names for features on Ceres. Back in October, the IAU adopted two naming themes for Ceres: craters will be named after agriculture deities, while other features were be named for world agricultural festivals. Russell showed this map that organizes Ceres' surface into quads, with each quad named after one harvest deity. As they did at Vesta, they will split the quads among the team as they begin to map Ceres, and these names will be applied to prominent craters within each quad. Thanks very much to Paul Schenk for sharing the map with me! Russell pointed out his own favorite quad name: Yumyum, located within Ceres' southern hemisphere.

I went ahead and applied these quad names to the digital elevation model. The crater with the bright feature in it is unfortunately right on the boundary between the Palo and Ebisu quads. The flat-floored huge crater I wrote about earlier lies mostly inside the quad called Kumba. The bright splash crater is in the quad named Hobnil.

The second talk of the session was most sensational: Andreas Nathues, presenting on early imaging results. At the beginning of his talk, he requested for bloggers not to blog it, but for reasoning I explained here, I'm writing about it anyway, as Alex Witze, Eric Hand, Irene Klotz, and others have already done. Nathues said that there was a variety of terrain on Ceres, ranging from smooth, to lineated, to rough. Many craters have flat floors; perhaps they are relaxed (meaning that the icy mantle has flowed over time to make the preexisting crater shallower, evening out the gravitational potential). He pointed to linear features throughout the surface, and says they already see some scarps. (Linear features and scarps are hallmarks of tectonics: geology driven by internal forces.) He called the large smooth crater the "pillowy-floored basin" and says it measures 270 kilometers in diameter. In general, the transition in crater shape from simple craters to complex ones with central peaks happens near a diameter of 25 kilometers.

Then he focused on the bright feature. It is located in the floor of a crater 80 kilometers in diameter. From its behavior as the globe rotates, he said, the bright feature appears to lie in a depression. The images that have been released to the public from the rotation animation do not show all of the photos of the bright feature, so the next point concerns images that I can't show you. "What is amazing," he said, "is that you can see the feature while the rim is still in front of the line of sight. Therefore we believe at the moment that this could be some kind of outgassing. But we need higher resolution data to confirm this." What he is saying is that as Ceres' globe rotates and the 80-kilometer crater's rim rotates into view, that rim should block our ability to see the bright feature on the floor of the crater. However, the bright feature is already visibly bright as the crater begins to rotate into view. Therefore, it must be vertically above the rim of the crater: it must be some kind of plume. "During the day," Nathues went on, "the feature evolves: it brightens. At dusk it gets fainter; at late dusk it disappears completely. We see this for cometary activity."

He moved to color data, showing a global map of Ceres as seen through different-colored filters. There was a striking asymmetry to the color: one hemisphere was much more red and the other much more blue. The images were taken from too great a distance to resolve the bright spot; it is smaller than 4 kilometers across. So they can say that its albedo is at least 0.4 (meaning that it reflects at least 40% of the light that strikes it), but it could be much higher. The color information over the spot is consistent with an icy surface, but this is not a unique interpretation. The feature has variable brightness with time: its brightness increases strongly as seen through the 550-nanometer filter around local noon.

Obviously, active outgassing on Ceres would be a big deal, if it really exists. Fortunately, Dawn will get much closer and will take much better images, which will hopefully confirm this discovery!

The last talk on actual Dawn data was given by Francesca Zambon, on the imaging spectrometer data, showing global maps. The spatial resolution of her map is only 11 kilometers per pixel at the moment, which is relatively coarse, but still better than Hubble. As was evident in Nathues' maps, Zambon's VIR maps showed a red hemisphere and a blue hemisphere; the bright spot is located at 20 degrees north, 240 degrees east, near the middle of the blue hemisphere. She showed some early temperature maps of Ceres' surface, and a surprising result: the bright spot showed no obvious temperature contrast with the area around it. But a different bright spot, the splash crater located at 4 degrees north, 8 degrees east, is markedly colder than the area around it. (You would expect cooler temperatures for brighter surfaces, all else being equal.)

The rest of the talks in the Ceres session concerned Earth-based observations, geophysical modeling, and future Dawn work. One of the interesting talks from that part of the session was by Tim Titus, who tried to use modeling to figure out where the "snowline" on Ceres is -- that is, the latitude at which ice is stable at the surface. Ceres has nights and days, of course, so the surface temperature varies with time, but those variations die out as you go beneath the surface. Titus defined locations where the subsurface never gets above 145 kelvins to be the location of the snowline on Ceres. For a variety of possible surface properties, a smooth surface would have a snowline somewhere between 40 and 60 degrees. If that surface is roughened (by, say, impact craters), then the snowline shifts poleward. So near-surface ice is stable near the poles, and comet-like ice sublimation could happen there, especially with help from seasonal heating or a meteor impact. On the other hand, plume activity at lower latitudes -- like the 20-degree-north position of the bright spot -- is happening in a place where near-surface water ice is not stable. Activity there would need to originate in a source of water ice that gets recharged somehow, such as by cryovolcanism. Of course, as Andy Rivkin pointed out during the question period, a sufficiently big impact could expose much more deeply-buried ice; he asked if Titus had modeled how often impacts would be expected to expose such deep ice. Titus replied that this was beyond the scope of his work.

A related talk, by Norbert Schorghofer, concerned a prediction for the GRaND neutron spectrometer results, which will not be able to begin acquiring quality science data until Dawn is in its lowest orbit, much later this year. Schorghofer's models suggest that Dawn GRaND should detect water ice within half a meter of the surface of Ceres, and he predicted that GRaND would observe this ice poleward of 60 degrees latitude. This assumes Ceres' current obliquity, which is very slight at only 3 degrees. As he spoke, I wondered if Ceres' spin axis has tilted more than this in the past, as Earth's and Mars' do. And later in the talk, he answered this question: even if Ceres' obliquity has varied, the prediction is still that there will be near-surface ice poleward of 60 degrees latitude. "This prediction can go wrong, but then it would mean something," he said. It could mean Ceres has lost a lot of near-surface volatiles due to impacts; or there has been true polar wander; or lots of dessication during an early period of radiogenic heating.

I enjoyed a later talk given by Thomas Davison on the shapes of Ceres' largest impact craters and how they may serve as a sensitive probe of the subsurface structure of Ceres. He modeled Ceres in three ways: with a dry olivine core; with a much wetter, serpentine core; and with a "mudball" core of mixed rock and water. Then he struck his model Ceres with asteroids of different sizes, arriving with speeds of 4 kilometers per second. In general, the mudball Ceres produced incredibly flat-floored craters, and the impact had little effect on the core-mantle boundary. The dry-core Ceres tended to produce the most surface topography, with prominent central peaks. The hydrated-core Ceres had more topography and prominent uplift of the core-mantle boundary underneath the crater. This kind of uplift would be obvious as a concentration of mass beneath the crater in Dawn's gravity data. Now, over geologic time, the original shapes of the craters may have been modified by relaxation, as ice flows from high places to low places to even out the surface; but the different appearance of the core-mantle boundary between the three cases should be visible in gravity maps.

All in all, there is a lot to look forward to on Dawn, and I can't wait for more pictures from closer orbits!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth