Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 12, 2014

Curiosity update, sols 727-747: Beginning the "Mission to Mount Sharp"

A lot has happened behind the scenes on the Curiosity mission in the last few weeks. The mission received a pretty negative review from a panel convened to assess the relative quality of seven different proposed extended planetary science missions, although NASA did fully fund Curiosity's extended mission (yay). Then, just a week later, the mission announced big news: they have arrived at Mount Sharp.

Wait, what? You would be right to be confused at this sudden declaration. The last time I checked the distance between Curiosity and Murray Buttes -- the planned entry point to the mountain -- there were several kilometers to go. Since then, the rover has made about one kilometer of progress, taking a turn toward the south. But the rover was stymied in her first attempt to proceed into a new kind of canyonland terrain. And the mountain is still decidedly far away, as seen in rover panoramas. How have they made it to the mountain? The surprise and timing have made people ask me whether this announcement is an attempt at "spin" or damage control. The short version of my answer: the timing of this announcement -- and the reaffirmation of Curiosity's science goals that accompanied it -- are certainly a response to the senior review report. Nevertheless, Curiosity really is just about to reach the very first exposures of the kinds of rocks that brought her to Gale crater in the first place, marking a turning point for the mission.

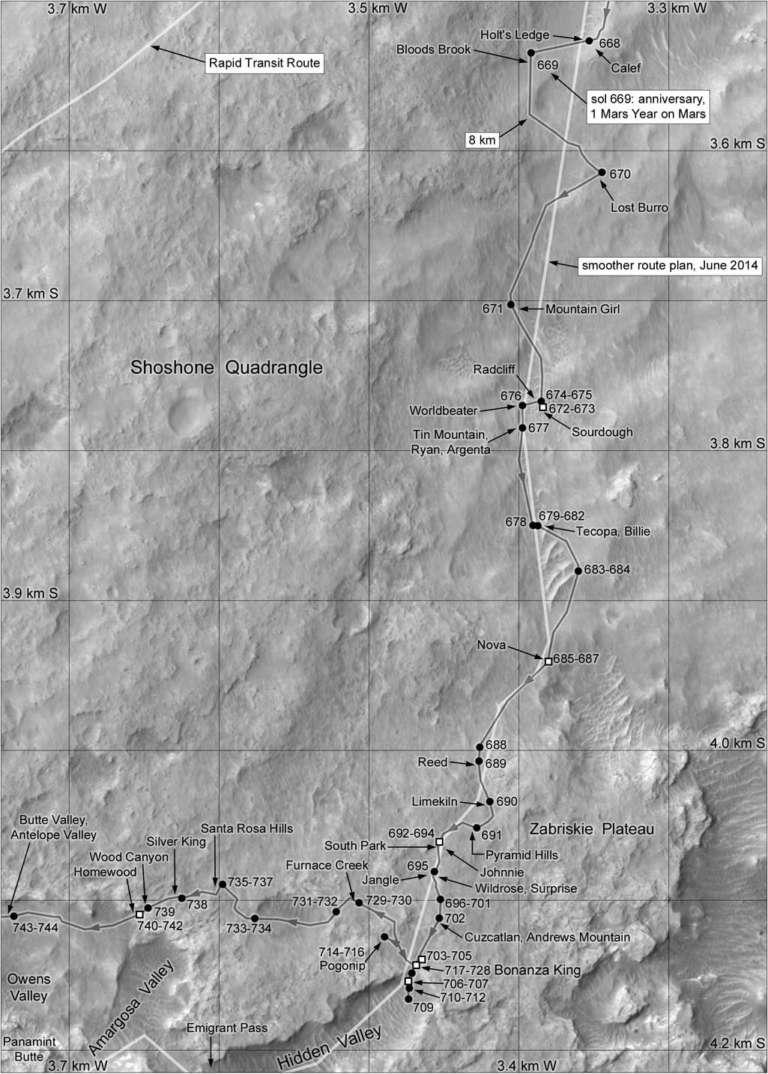

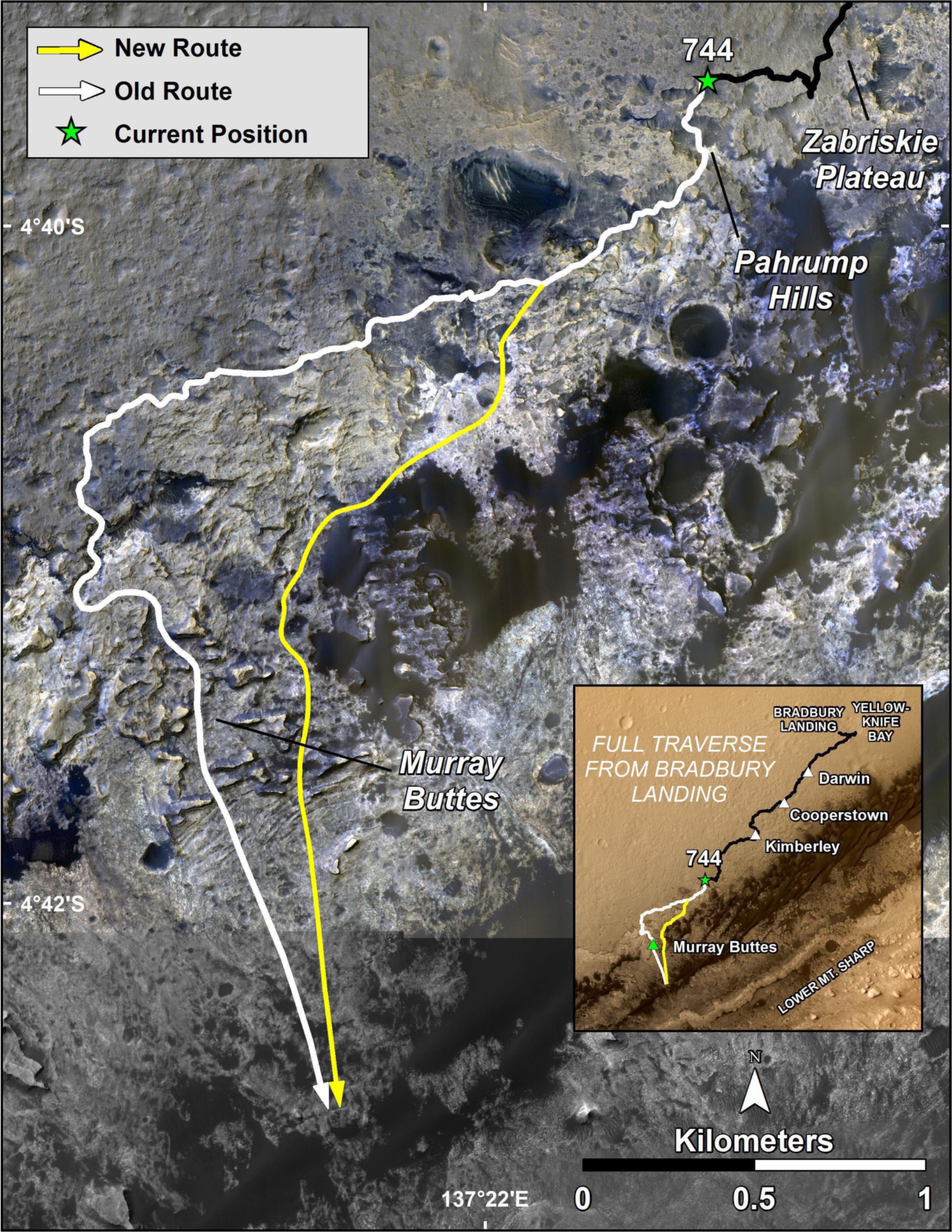

So, how is it that Curiosity could have arrived at Mount Sharp when we thought it was still several kilometers away? The key is that turn to the south -- and a different working definition of "arrival" at the mountain than rover fans have been using. The original "rapid transit route" would have had Curiosity driving along rocks of a type the rover has seen before for nearly the entire distance to Murray Buttes: crater-floor filling sediments, mostly sandstones and conglomerates, which formed after Mount Sharp. But by turning south, Curiosity has taken a course that takes her much closer to the mountain, much earlier, than she would have, absent the wheel problems that forced her to change her trajectory. You can see how the two paths diverge in this route map from Phil Stooke. The old planned path, in upper left corner, curves off to the left (southwest); Curiosity has been driving almost due south, straight at the mountain.

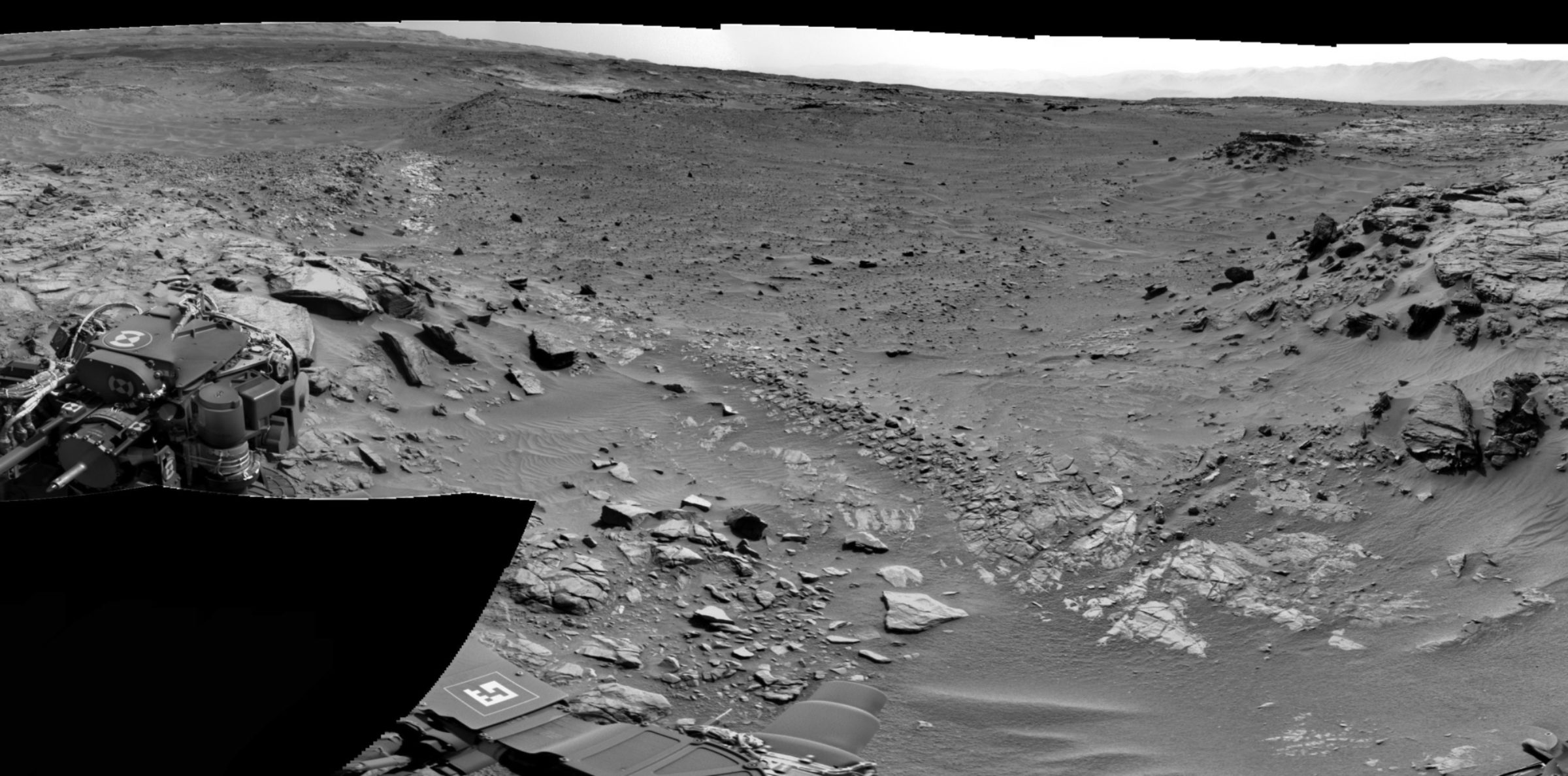

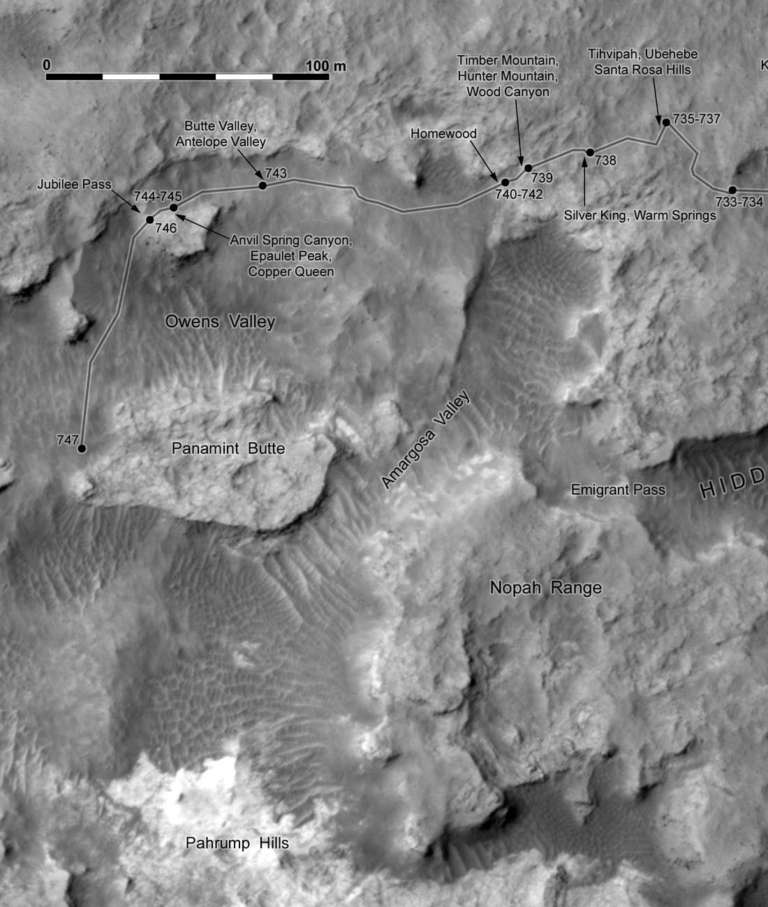

But isn't the mountain still off in the distance, you might ask? It's a fair question. Here's a recent view from Curiosity, taken on sol 740 (September 5). At the moment that she captured this panorama, she had completed her detour around the too-soft sand of Hidden Valley, and was descending down a ramp into the much less sandy Amargosa (to the left) and Owens (to the right) Valleys. The dramatic buttes and yardangs of Mount Sharp that we've been able to see since landing are still stubbornly parked on the horizon, several kilometers away. But in the middle distance is a bright patch of rock named Pahrump Hills. This patch of rock is what the mission means when they talk about arriving at Mount Sharp. I'll explain why in a moment.

Here is a map view of Curiosity's most recent few days of driving; you can see the bright spot of the Pahrump hills near the bottom.

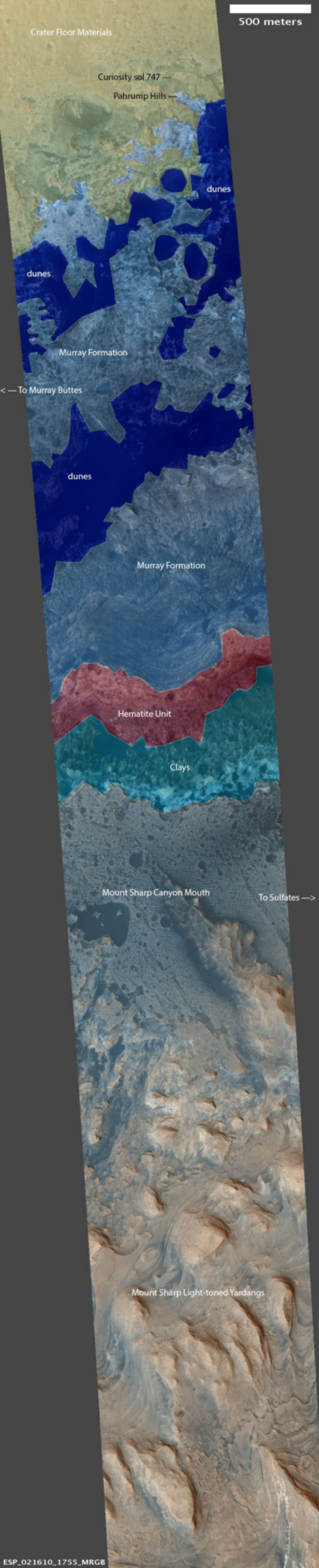

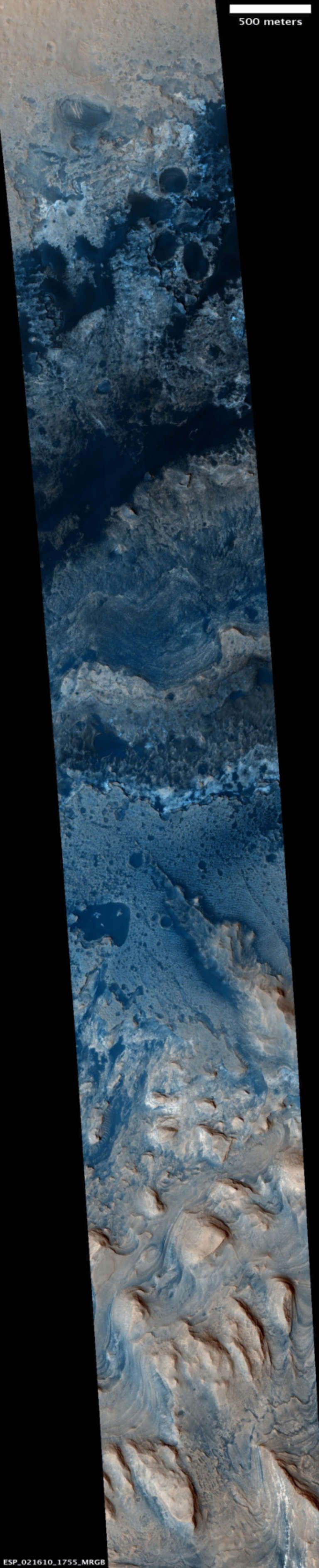

To explain what Pahrump Hills has to do with arriving at Mount Sharp, let's view this patch from orbit, in its broader context. Below is a color HiRISE swath that includes Curiosity's current position (near the very top of the long swath) and nearly every kind of rock that the mission hopes to visit during the extended mission, which they have dubbed the "Mission to Mount Sharp." You can slide back and forth between the HiRISE image and my extremely crude map to see all of the rock types that lie ahead of the rover. (Note that you don't need to use the mouse to grab the elusive green slider; clicking anywhere within the image will move the slider to that vertical position in the image.) About a third of this swath is covered by the Paintbrush unit, now renamed the Murray formation. As of today, Curiosity has just about reached the northernmost outlier of the Murray formation on this image, the spot that the team has named the Pahrump Hills. Pahrump Hills and Murray formation really stand out as being substantially brighter than the reddish, cratered landscape Curiosity has traversed so far. It's a fundamentally different rock unit.

Here is how the mission described the Paintbrush unit -- now called Murray formation -- in their extended mission proposal. (Follow the link to the PDF proposal to see the figures referred to below.)

The paintbrush unit derives its name from its distinctive texture, as seen from orbit in High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) image data. It is over 100 m thick and lacks any evidence of the simple layering that is so ubiquitous in other rock formations of Mt. Sharp, Yellowknife Bay, and the plains in between. The unit has higher thermal inertia values compared to overlying stratigraphic units, and sparse detections of hematite, sulfate, and possibly other minerals (Figure 2-1a–c). Locally, there are suggestions of steeply to even vertically dipping, folded strata (Figure 2-1b). This complexity results in a patchy texture, with streaks reminiscent of paintbrush strokes at various trends. Based on this limited information, it is possible that these rocks form a completely different rock package from what overlies them; possibly, it represents an older sequence of stratified rocks that has been complexly deformed, possibly by impact events along an unconformity surface, before being overlain by undeformed strata. Alternatively, it may represent something like slump-folded fine-grained rocks, such as mudstones. It seems unlikely to be crater central peak or peak ring material because it is off-axis and at an elevation higher than what might be predicted. However, each of these hypotheses is testable with Curiosity. Sampling the paintbrush unit would allow us to assess the peculiar nature of lowermost Mt. Sharp.

So the team interprets the Murray formation to be underlying all the rocks of Mount Sharp. What exactly it represents, they aren't sure; there is wide range of hypotheses under discussion. But if the old age turns out to be true, Murray formation rocks are older than Mount Sharp, and are consequently the oldest unit that Curiosity ever has, or ever will, examine. When she gets there, Curiosity will have arrived at the beginning of the Martian story that she will be able to investigate. And that's really, really important.

Remember: climbing Mount Sharp wasn't the goal of all the driving that Curiosity has been doing. The goal has always been to reach ancient clay-rich rocks and then to perform a geologic traverse up through the layers of rocks that record a time when Mars had more habitable environments. If Curiosity has, in fact, arrived at rocks that underlie Mount Sharp, then she has achieved her driving goal, completing the "go-to" phase of the mission from her safer landing ellipse to her scientific target, and it's now really time to begin the scientific work.

What happens after Pahrump Hills? More driving; but all of the driving will be through the kinds of rocks Curiosity was sent to Mars to study, beginning with the Murray Formation and eventually moving on through hematite and clay units, possibly to the distant sulfates. It's going to make the mission fundamentally different in character. They still need to move, in order to accomplish their goals of traversing time as recorded in ancient rock units, but it'll be movement across a science-rich landscape than they've enjoyed previously. Here are the science plans for the extended mission, in a nutshell (again, from their extended mission proposal):

- The diverse layers of sedimentary rock exposed in the foothills of Mt. Sharp will guide our understanding of what environmental factors may have enhanced the habitability of Mars as a young planet and, within those environments, what factors may lead to preservation of organic carbon.

- The four major layers targeted in [the extended mission] have likely recorded a very broad range of environmental conditions, and therefore promise variation in habitability and potential for organic preservation. However, these ideas derive from incomplete orbiter data and Earth-based experience; in situ analyses and sampling are required to test them.

- By studying each of the four layers (and potentially others), MSL will observe transitions between habitable and uninhabitable environments, see the spectrum of conditions that favor or preclude organic preservation, and seek to link those to the environmental history of Gale Crater, as a sample of the planet’s early history.

The mission has been under a lot of pressure to drive, drive, drive, in order to reach Mount Sharp, especially since the prime mission technically ended in August without Curiosity achieving that goal. (I say "technically" because although the prime mission is over, they are currently in sort of a quasi-extended prime mission for a couple of months, bridging to the beginning of fiscal year 2015 on October 1, which is when the extended mission officially starts.) But the senior review opined that the Curiosity mission should drive less and do more science.

Those competing pressures -- drive to Mount Sharp, versus stop and do more science -- is why they ballyhooed this moment as the "arrival." The mission has been intending to stop and do science in the Paintbrush Unit / Murray Formation for some time. Indeed, when they paused to drill at Bonanza Hills last month, they thought they would be getting a jump on their Murray formation science in a small outlying outcrop of the rock. But it didn't work out that way; the target they chose turned out to be unsafe for drilling. Once they do get to Pahrump Hills, you're going to see a change in the style of a mission, but it's not a change that results from the senior review; it's a change that results from them arriving at their scientific target. What they had planned to do (stop and likely drill at Pahrump Hills, spending a couple of months at least on a detailed scientific campaign) is consistent with what the senior review directed them to do. In fact, they'd already be at that target if not for the frustrating month that preceded this one.

Pahrump Hills is not where most of us were thinking when we thought of "arriving at Mount Sharp." However, if it is true that the Murray Formation underlies the interesting hematite, clay, and sulfate-rich rocks that make up the lower levels of the mountain -- and I see no reason to disagree with that interpretation -- it is absolutely correct to say that when Curiosity gets to a good outcrop of Murray Formation rocks, she will have arrived at the destination of her long traverse and the beginning of her Mission to Mount Sharp.

If I ruled the world, I probably would not have announced the arrival this week; given the activity of the Martian gremlins in the last month I would've waited until I saw Curiosity's wheels firmly on Pahrump Hills outcrop just to be really sure she had got there before announcing it. But I understand that the senior review demanded a response, and the mission chose to respond sooner rather than later. I, for one, am happy to get information out of the mission sooner rather than later, so I'm certainly not complaining about the timing of the press briefing. I just hope that those Martian gremlins give the mission a break and allow Curiosity to arrive at the place they've said she's gotten to! She should get there next week, gremlins willing.

For the thorough details on sol-by-sol activities of the rover over the last three weeks, read the updates from Ken Herkenhoff, Lauren Edgar, and Ryan Anderson, as posted to the USGS Astrogeology website:

Sol 726 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: Busy Uplink (20 August 2014)

We were hoping that the Sol 726 plan would include full drilling of the Bonanza King target, but the downlink from Sol 724 showed that the mini-drill activity did not complete successfully, probably because the rock moved during drilling. Planning is still restricted, so the Sol 725 plan had not yet been sent to the spacecraft when the Sol 724 data were received. After much discussion, we decided to send the Sol 725 plan to the rover, recognizing that some of the ChemCam LIBS observations would be precluded by software because the arm will be in the way. We also decided to retract the drill and take all of the MAHLI and all of the other imaging data of the mini-drill hole that were originally planned for Sol 724 but were not acquired after the drilling was aborted. So it was a busy day for me and the other people scheduled to support MAHLI uplink!

Sol 727 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: Stellar Observations (21 August 2014)

While we wait for data acquired on Sol 726 to be received later tonight, the Sol 727 plan includes only remote sensing observations. Mastcam and ChemCam will observe both nearby and distant targets during the day, then will attempt to observe some stars after dusk. The goal of the star imaging is to determine how accurately the instruments can be pointed, to support planning for potential observations of comet Siding Spring when it passes very close to Mars in October. An additional benefit, if these stellar observations are successful, is that the data will be useful for checking the radiometric calibration of the cameras.

Sol 728 -730 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: Driving Again (22 August 2014)

After much study and discussion, the MSL team decided not to attempt to drill again into the rocks in front of the rover. On Sol 728, ChemCam and Mastcam will observe several nearby targets and the observation tray on the rover. The Sol 729 plan is dominated by the drive, with a single set of MAHLI wheel images. After the drive, on Sol 730, multiple instruments will observe the sky, ChemCam will shoot blind at the surface to the right of the rover, and MARDI will acquire another image during twilight. All of the MAHLI and MARDI activities are pretty standard, so it was an easy planning day for me as MAHLI/MARDI uplink lead.

Sol 731 Update from Lauren Edgar: Large Crater Ahead (25 August 2014)

Curiosity is back to driving! We are taking the high road around Hidden Valley to avoid potentially deep ripple fields, and making our way towards a large crater. This image from Sol 729 shows the crater just ahead of us. The Sol 731 plan includes a drive to the rim of the crater and some ChemCam and Mastcam observations to characterize the local geology. In the pre-drive targeted science block, Curiosity will investigate targets named “Beck Spring,” “Eagle Mountain,” “Furnace Creek,” and “Rainstorm.” After the drive we will acquire our standard post-drive imaging and some systematic observations. Tomorrow is a soliday (a day without planning to allow Earth and Mars schedules to sync back up), so there will be no blog, but the sol 732 blog will be posted the following day.

Sol 732-734 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: Multi-sol planning (28 August 2014)

Yesterday we did not receive as much data as expected, so could not drive as originally planned. Therefore, the Sol 732 plan was dominated by targeted ChemCam and Mastcam observations of "Lippincott," "Hall Canyon," and "Keeler Canyon." Today we received all the data needed to plan a nice drive, plus MastCam and ChemCam observations of a target dubbed "Red Pass" on Sol 733. We are planning 2 sols today to get a head start on the long weekend plan. On Sol 734, ChemCam will take spectra of the sky during the day, then SAM will sample the atmosphere overnight. The goal of these observations is to compare the atmospheric chemistry measured by the two instruments.

Sol 735 -737 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: Rapid Traverse Planning (31 August 2014)

The volume of data sent from MSL to Earth has been less than usual over the past few days because the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) went into "safe mode," a software state that ensures ample solar power and telecommunications. This has happened several times before on MRO, and another prompt recovery is in progress. Without MRO data relay, MSL operations depends on relay through the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which was not expected to be received until almost 11:00 Friday. Therefore, the planning schedule was changed to a "rapid traverse" sol, in which science observations are limited to allow the day's activities to be prepared and reviewed more quickly. This allowed us to plan a rover drive when we otherwise would not have been able to when starting at 11 AM Pacific time. So the Sol 735 plan includes another ChemCam passive sky observation and a Mastcam panorama of the sand dunes that the rover drove past on Sol 733. Only REMS atmospheric measurements are planned for Sols 736 and 737.

Sol 738 Update from Lauren Edgar: Pahrump Hills (2 September 2014)

Curiosity is driving across a plateau towards an ingress point into “Armargosa Valley.” This image from Sol 735 shows our drive-direction: We are working our way towards the bright patch of rocks in the upper left portion of the image, known as the “Pahrump Hills.” Today’s plan includes some ChemCam and Mastcam observations of the targets “Tihvipah,” “Santa Rosa Hills,” and “Ubehebe” to characterize the local geology. The plan also includes a drive and standard post-drive imaging. In the afternoon, Curiosity will acquire a ChemCam blind target, and several Navcam movies to monitor the atmosphere and search for clouds. atmosphere and search for clouds.

Sol 739 Update from Lauren Edgar: Rough Road Ahead (3 September 2014)

Curiosity has almost reached an ingress point into Armargosa Valley.

To get into the valley, Curiosity will have to cross some fairly rough terrain, but this also provides an opportunity to analyze the bedrock as we go. The plan today includes ChemCam and Mastcam observations of the targets “Silver King” and “Warm Springs.” We are also planning a ~30 m drive, which should place us close to the edge of Armargosa Valley. After the drive, Curiosity will acquire some standard post-drive imaging, and a 360-degree Mastcam mosaic to document the terrain from our vantage point. Early on the morning of Sol 740, Curiosity will acquire another Mastcam mosaic to characterize the Pahrump Hills, an interesting patch of bright rocks where we hope to do a more detailed investigation.

Sol 740 Update from Lauren Edgar: Approaching Amargosa Valley (4 September 2014)

Curiosity is about to ingress into Amargosa Valley. This Navcam image from Sol 739 shows some of the beautiful layered rocks that we have been driving over and analyzing recently. The plan today includes ChemCam and Mastcam observations of the targets “Timber Mountain,” “Hunter Mountain” and “Wood Canyon,” as well as a Mastcam mosaic of “Owens Valley,” and a long distance ChemCam observation of Pahrump Hills. The drive today will be short (~12 m) to the edge of the ingress to Amargosa Valley. At the end of the drive we will acquire better imaging into the valley to help plan the ingress drive, which will hopefully occur over the weekend. After the drive on Sol 740, Curiosity will acquire post-drive imaging for targeting, including Mastcam imaging of the workspace to prepare for possible contact science over the weekend, and standard post-drive imaging.

Sol 741-743 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: Busy Weekend (5 September 2014)

The weekend plan is very ambitious, with a bunch of targeted remote science observations on Sol 741, contact science on Sol 742, and a long drive on Sol 743. It has been a busy day for me as SOWG Chair, partly because our favorite contact science target was too difficult to reach with the arm instruments and we had to scramble to find another target that was both reachable and scientifically interesting. We settled on a target dubbed "Homewood," which will be examined by MAHLI and APXS. We now have a good view of the path into Amargosa Valley, so we expect to make good progress on Sol 743.

Sol 744 Update from Ryan Anderson: Driving in Amargosa Valley (8 September 2014)

The weekend plan was successful: we got good data from the Homewood contact science target, plus a nice long 92.6 meter drive on Sol 743. The plan for Sol 744 is to do routine wheel imaging, plus Mastcam mosaics of a mesa in front of the rover named “Jubilee Pass,” and a mosaic of the north and south walls of Amargosa Valley. ChemCam will be zapping two targets named “Butte Valley” and “Antelope Valley,” and there will be supporting Mastcam images of those targets too. Navcam will be taking a movie watching for clouds above Mount Sharp.

Sol 745 Update from Ryan Anderson: Untargeted Science (9 September 2014)

We have not received any data from sol 744 yet, so sol 745 is a simple day of untargeted remote sensing. ChemCam has an observation of the sky (with the laser off) to measure the gases in the atmosphere, and a “blind” LIBS observation off to the right of the rover. Mastcam will take a context image for the ChemCam blind observation so we can tell what we shot, and will also make some “tau” observations of the sun to measure how much dust is in the atmosphere. We will also do standard DAN and REMS environmental monitoring.

Sol 746 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: NASA Teleconference (10 September 2014)

The Sol 744 drive went as planned (32 meters), and another drive is planned for Sol 746. Because we can't see the terrain immediately beyond the small saddle dubbed "Jubilee Pass," the rover will drive about 9 meters into the saddle, then take images of the other side. But first, ChemCam and Mastcam will observe targets dubbed "Anvil Spring Canyon," "Epaulet Peak," and "Copper Queen." After the drive, another ChemCam "blind" observation of the surface to the right of the rover is planned.

Sol 747 Update from Ken Herkenhoff: Pahrump Hill mosaic (11 September 2014)

The Sol 746 drive put the rover in a good location for imaging the terrain ahead, which looks good for a long drive on Sol 747. The Sol 746 data did not hit the ground until after 11:00 PDT (as expected), so today is another "rapid traverse" planning sol and the time available for science observations is therefore more limited than usual. Because the view of the bright "Pahrump Hills" outcrop is good from our current location, Mastcam stereo mosaics of Pahrump Hills and other features of interest are planned for the morning of Sol 747. The Pahrump Hills mosaic should be useful in planning investigations of this nice outcrop of the rocks that form the base of Mt. Sharp.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth