Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 03, 2014

Seven Mars spacecraft attempted observations of comet Siding Spring. How did they go?

It's been two weeks since comet Siding Spring passed close by Mars, and six of the seven Mars spacecraft have now checked in with quick looks at their images of the encounter. None of the spacecraft photos of the comet is visually spectacular -- there are no enormous fireballs streaking across Martian skies. What the released images do show us is that this is a terrific data set taken from very close range on an Oort cloud comet; over the coming months and years, we'll enjoy the fruits of careful scientific investigation of a unique data set.

And it's worth taking a moment to appreciate how we got these photos. A year ago, we discovered a teeny tiny object that had never visited the inner solar system before; we predicted that it would pass by another planet; we already had five spacecraft at that planet, and two more preparing to launch; and we commanded all these autonomous robots to catch the comet as it flashed by at 55 kilometers per second.

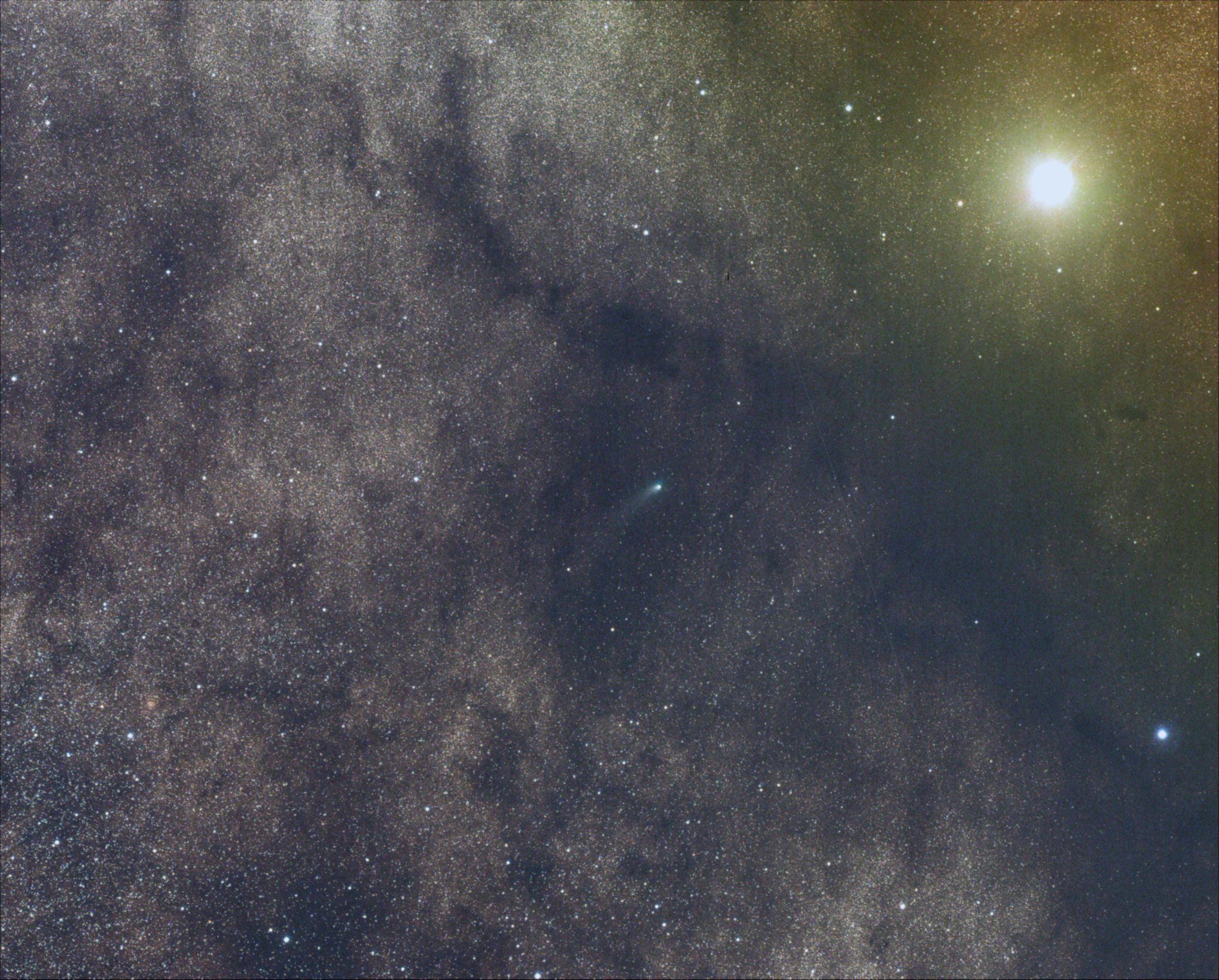

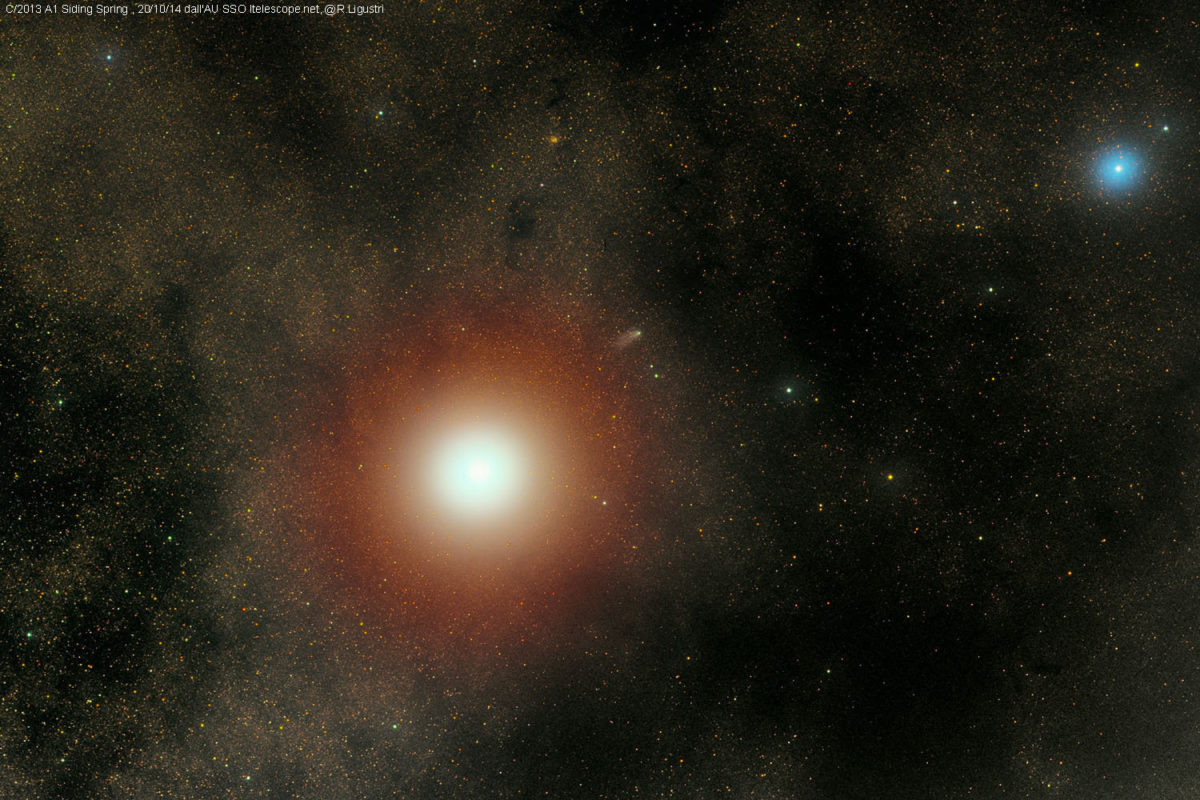

The very best photos of the close approach of the comet to Mars were actually not taken from any of the Mars spacecraft; they were taken by astronomers on Earth, mostly amateurs. Here are three of my favorites, taken by three different amateur astronomers from telescopes at Siding Spring Observatory, where the comet was discovered last year.

For more amateur views, check the Bad Astronomer's and Universe Today's galleries, or try the Realtime Comet Gallery at spaceweather.com.

All five Mars orbiters successfully performed the tricky observations that they were commanded to do, but not all five produced results. Three of the five (Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, MAVEN, and Mars Express) definitely detected the comet. Sadly, the comet was not bright enough in infrared wavelengths for Odyssey to detect it with its THEMIS instrument, Phil Christensen has told me. I've heard nothing about ISRO's Mars Orbiter images, but I presume we would have heard something by now if the comet were detectable in them.

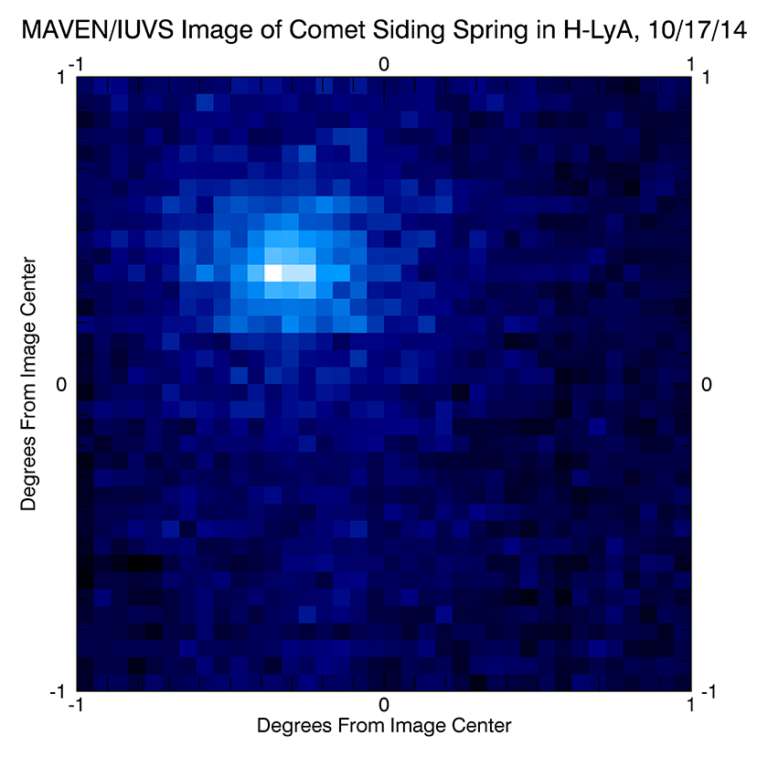

It turns out that one of the first spacecraft to detect the comet was the MAVEN orbiter, newly arrived at Mars. It captured this view of the hydrogen surrounding the comet two days away from its approach to Mars:

You can see hydrogen out to about half a degree away from the comet nucleus, which was about 150,000 kilometers. The MAVEN team points out that this is comparable to the distance of the comet's closest approach to Mars, which means that hydrogen atoms were slamming in to Mars' atmosphere at relative speeds of 56 kilometers per second. This photo hints at the possibility of a pretty interesting data set from MAVEN.

The most anticipated photos of the comet were those of Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's HiRISE camera, which was the only one that could hope to resolve the comet's nucleus. HiRISE was actually able to spot the comet 12 days before it arrived at Mars, and it's a good thing they did, because without those early photos, they would not have been pointing in exactly the right spot to image the comet when it got much closer. They haven't released the photo taken 12 days before closest approach, yet.

Fortunately, HiRISE did get the necessary update on the comet's position and successfully imaged the comet at very high resolution. But the photos don't show as many pixels across the comet as predicted, because the comet turned out to be smaller than predicted.

Although the comet's small size is a little disappointing for the images, it's actually quite an exciting scientific result, probably. The size of unresolved solar system objects is estimated by taking its absolute magnitude (which can be measured reasonably precisely) and assuming an albedo, or reflectiveness, of its surface. All the comets we've ever seen up close are exceedingly dark, with albedos around 5 percent, give or take a couple percent. The fact that Siding Spring turned out to be smaller than predicted means we guessed its albedo wrong. Its surface is more reflective than we predicted. Which is wonderful, because it's consistent with the hypothesis that comets are usually dark because the Sun has baked away brighter ices, and that they start out their cometary lives much brighter. So we may have just learned something about the nature of bodies that are too far away from the Sun for us to see. (I am hedging all of my language here because I would like to see a bright comet nucleus albedo confirmed by more quantitative analysis and, ideally, evidence from another one of the spacecraft.)

I find the HiRISE images to be a little bit difficult to interpret. One important piece of information is that the phase angle of the observation is about 110 degrees, so we're seeing the nucleus of the comet in a crescent phase. That is, most of the nucleus of the comet that is in the field of view is actually the night side. The bright blob is not the nucleus; the nucleus is about a quarter of the bright blob, and about three quarters dark pixels next to the bright blob. The sunlit crescent of the comet is hard to differentiate from the brightest inner part of the coma.

For comparison, here is a Deep Impact image of comet Tempel 1 taken after their flyby in 2005. The phase angle here is also about 110 degrees; you can see how it could be hard to tell the nucleus from the coma, especially with a much lower-resolution image. It's not a perfect comparison because Tempel 1 was not as active as Siding Spring -- it isn't the coma you're seeing here, it's the ejecta from Deep Impact's impact. Siding Spring's coma wouldn't emanate from just one spot on the comet's surface; it would be coming from numerous locations, and it may just blend in to the nucleus in the HiRISE photos.

I've heard that Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's Context Camera also successfully detected the comet, in a ridealong observation with HiRISE. They haven't released the photo, I'm assuming (without having seen it) because it's nothing more than a speck -- it would be underwhelming.

Mars Reconnaissance orbiter CRISM got a really good look at the coma. CRISM is an imaging spectrometer; it doesn't have the sharp spatial detail of HiRISE, but every single pixel in a CRISM image is a full visible and near-infrared spectrum at that point, which can be interpreted by spectroscopists to infer the presence and sometimes the abundance of different molecules. The images below don't tell you all that, but they show color that varies from place to place, which means that this is a really rich data set that is going to tell us something very specific about the comet's constitution, once the scientists have had time to interpret the data.

For CRISM geeks: The three colors used in the image above represent the amount of signal in three regions of the visible and near-infrared spectrum. For each pixel, the median of 850-980 nanometers is displayed as red, 720-850 nanometers as green, and 500-630 nanometers as blue. There is rich signal in each one of those pixels, just waiting to be decoded into compositional information.

The last orbiter that I have been waiting for is Mars Express. Its High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) also took photos of the comet, and one set was finally released yesterday. Here it is, a six-image animation of photos taken with the Super-Resolution Camera, the small, slighly out-of-focus framing camera that is a small part of the HRSC instrument.

I included this animation in the blog post for completeness, but I have to admit I don't really know how to interpret it. My brain really wants to see an irregularly-shaped comet nucleus tumbling in space. But that is most definitely not what the animation is showing us. Each pixel in the image is 17 kilometers across -- it was taken on the orbit after closest approach, so the comet was already pretty far away. We know from HiRISE that the comet nucleus is less than a kilometer across, so its light only contributes to about one thousandth of one pixel's area in the SRC animation. Everything we see in that blob moving across the image is from the coma. Even so, I can't tell you what I'm looking at, because the pixels are either black or white -- it's a one-bit animation. I don't understand why that is. The one thing this image does tell you is that Mars Express was successful in targeting the comet; hitting the SRC field of view is no easy task. Which bodes well for the other experiments that Mars Express performed.

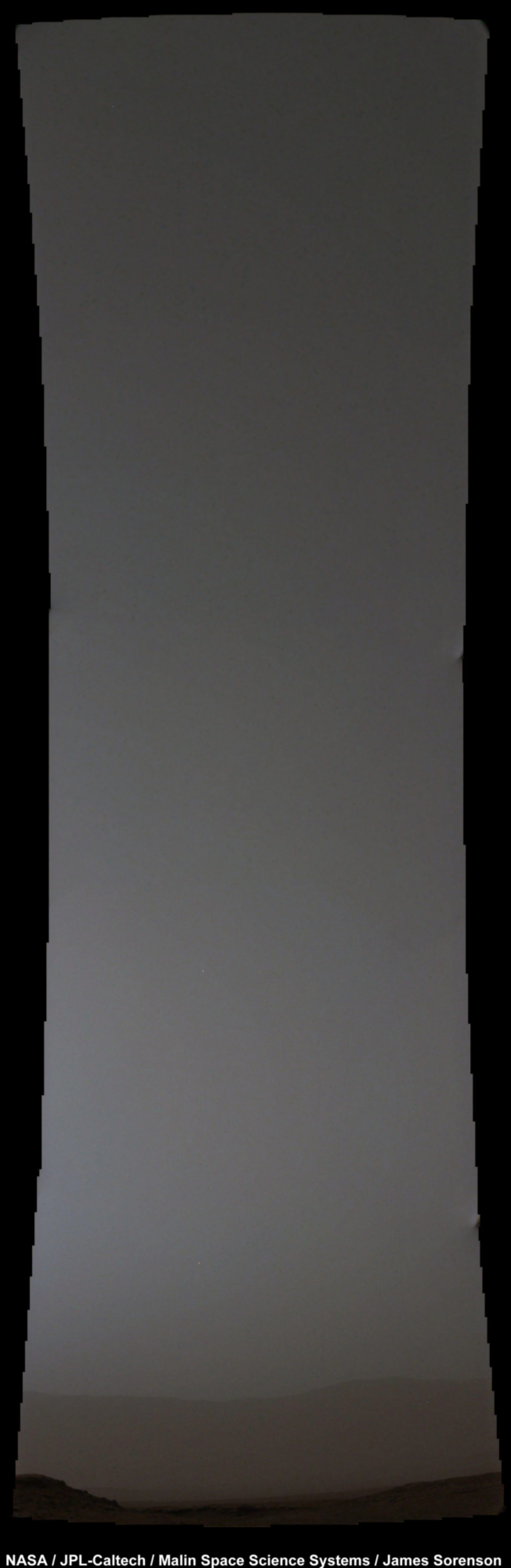

There's one more spacecraft that attempted observations: Curiosity. For Curiosity it was hard to see the comet because it appeared in very bright twilight, close to the horizon, and a week's worth of rising dust activity made the twilight even brighter than it has usually been. The comet's there, but it's just a single pixel, almost invisible unless you enlarge the photo all the way (click through twice and look close to the upper left corner). But the images that it took to make that observation are beautiful all on their own, even without containing any comet in them.

This post just represents a smattering of the huge amounts of data that were collected by orbiters and rovers during the encounter. It'll take months or, more likely, a couple of years for all the results to come out. There will probably be a dedicated session at a future science meeting about the Siding Spring encounter with Mars, and after scientists have presented and discussed their individual work there, they will prepare papers for a special issue of a peer-reviewed journal covering all the different spacecraft's findings. It's not a fast process, but it's a thorough one. We have the data in hand, but it will be a while before we learn what it has to tell us about the nature of comet Siding Spring.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth