Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 11, 2012

Spring arrives to Vesta's north pole, as Dawn departs, plus a request for citizen scientists

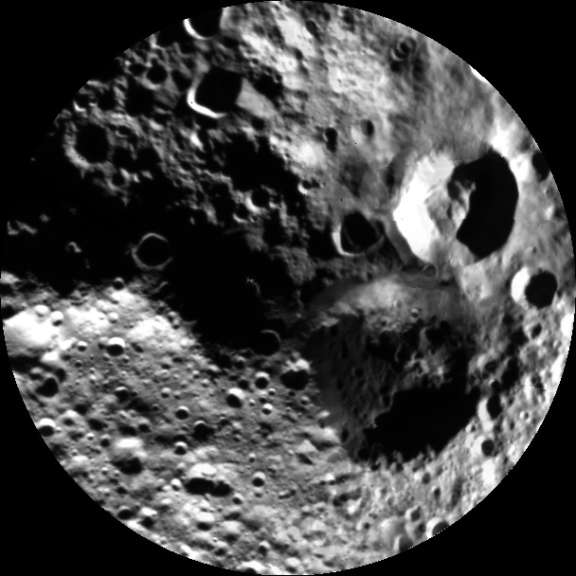

Today the Dawn mission released what they said would be their last captioned daily image release until the Ceres phase of the mission begins in 2015. It shows shadowy regions of Vesta's north pole that were hidden in winter darkness when Dawn arrived last summer. Dawn managed to stick around long enough to see most of the pole before energizing its ion engines to embark on the cruise to Ceres.

This photographic look at the north pole is important for a couple of reasons. There's the obvious: it means there won't be a "here there be dragons" region on our map of Vesta. But the science team really needed to see the north pole in order to understand Vesta's interior. How does that work?

Vesta is a lumpy place, and the north polar winter was hiding some interesting topography. Dawn's science team needed to map that topography in order to develop a precise measurement of Vesta's volume and therefore its density, a crucial piece of information for guessing at the nature of its interior.

The topography is also an important input into understanding what Vesta's gravity field means about how its mass is distributed. They tracked Dawn very precisely to notice all the wiggles and bumps in Dawn's orbit that result from extra mass here and missing mass there. A planet's gravity field usually correlates well with its topography -- if you have a mountain sticking up, that's a bit of excess mass that affects the course of a spacecraft -- but if you assume a density for the planet's crust and then correct for the missing and excess mass due to topography, the residual "gravity anomaly" often shows surprising features, clues to inhomogeneous distribution of mass inside the body, places where there is unusually dense material or unusually light material hidden beneath the surface.

To pass the time during Dawn's long journey, you can help the science team out in the recently announced Vesta Mappers project. Just like Moon Mappers, Vesta Mappers requests citizen scientists' help in mapping craters and any unusual features in high-resolution images of Vesta. I gave it a shot this morning and noticed that Cosmoquest has made some subtle improvements to its interface that make it even easier to use than it was previously. But Vesta's craters are not easy to map; it's a very heavily cratered surface, and many of its craters are very subtle. I find myself using a trick I learned in drawing classes: to close my eyes most of the way while looking at the image, which has the effect of filtering out detail, leaving behind the broader patterns of bright and dark. That helps reveal subtle craters that are obscured by more recent ones.

Sadly, Vesta Mappers seems to be the only way that us members of the public can see Vesta camera data (other than the now-ended daily image releases), at least for the time being. The Vesta approach, suruvey, and high-altitude mapping orbit data were supposed to be available from the Planetary Data System as of last month, but they are not there. A version was actually released some time ago -- and I posted a few pictures from it -- but then it was taken down, because it was not an approved release. The holdup is a dispute between the mission and the IAU over the choice of longitude system for Vesta. You can read about that in a Nature article here.

I am actually sympathetic to the mission's point of view, but I doubt that the choice of coordinate system is the whole story; we may be exploring space with robots and computers but it's humans back on Earth that are in charge, and just occasionally, humans are not quite rational. Even scientists!

It's frustrating to me because in all of its public image releases, the Dawn mission has not yet released an approximately true color global view of Vesta. That's all I want: a color portrait of the world they've just spent more than a year exploring. Ordinarily, if a mission team doesn't produce an image I'm looking for, it's easy for me to rectify that, by going into the data myself and making the illustration I want. But I can't do that for Vesta until the data become public.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth