Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 20, 2011

A fourth moon for Pluto

That's right: Hubble observations have yielded the discovery of a third small body orbiting Pluto and Charon. The faint thing, mellifluously designated S/2011 (134340) 1 but which is being referred to as P4, is only 10% as bright as Nix, the larger of the two previously known small moons. All three of these were discovered by the same team, which includes Mark Showalter, Alan Stern, Hal Weaver, Andrew Steffl, and Leslie Young. The initial discovery was made on June 28, but it's since been "precovered" (though it's very hard to detect) in Hubble images from as far back as February 2006.

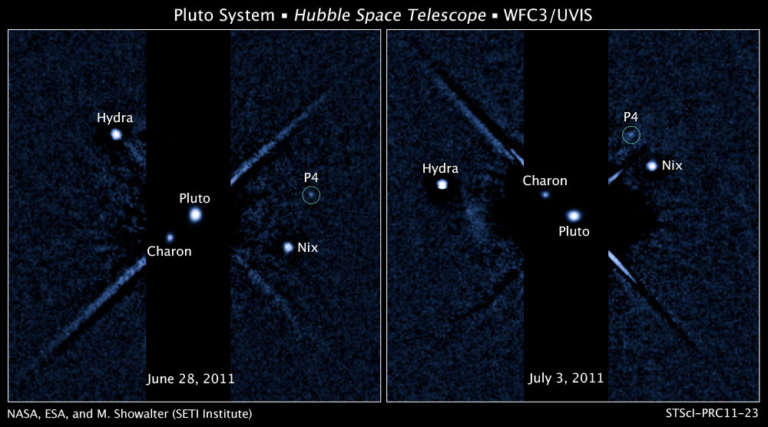

Since I seem to be the last space blogger to have gotten this news, I'll try to make up for that with thoroughness! First of all, here's the discovery image and a follow-up one:

When Hubble discoveries are announced, they seem to be all over the Internet in a matter of seconds. Don't bother reading these instant articles, which are usually just a rehash of the press release. Instead, go straight to the HubbleSite, where they have the press release as well as numerous versions of all the relevant images (labeled and unlabeled). Another tab, "The Full Story," often has extra sciency facts about the event, but in this case it just repeats the release. But there's more information available in the form of the International Astronomical Union's Electronic Telegram No. 2769, which documents the discovery in detail.

To make the discovery, Showalter and his team pointed Hubble at Pluto and took very long, eight-minute exposures. (These long exposures are what permitted them to make the discovery -- previous observations that yielded up Nix and Hydra had shorter exposures.) They observed it in five sets of images: two on June 28, two on July 3, and one on July 18. That 20-day span gave them enough information to determine that its motion from day to day can be explained with a circular orbit about 59,000 kilometers from the Pluto-Charon barycenter, with an orbital period of about 32.1 (±0.3) days. That orbit puts it squarely between Nix (48,700 kilometers) and Hydra (64,800 kilometers).

It is very faint, only about 10% the brightness of Nix. Without knowing the brightness of the surface it's difficult to estimate how large the new moon is, but it's certainly smaller than Nix, probably considerably smaller. Recent work has suggested that Nix and Hydra have relatively dark surfaces, making their sizes likely larger than earlier estimates -- 106 kilometers for Nix (which is thought to be very dark, albedo 0.06) and 81 kilometers for Hydra, according to Dave Tholen's presentation at the Division of Planetary Sciences meeting last year. So a back of the envelope calculation: if P4 is 10% the brightness of Nix but has the same kind of surface, that means it has roughly 1/10 the reflecting area or about 1/3 the diameter. If P4's albedo is brighter, then it'd be smaller. The diameter estimate in the NASA release is 13 to 34 kilometers, consistent with that back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Showalter and the rest of the team have been using Hubble to learn as much as possible about the Pluto system before New Horizons gets there in 2015. You may wonder: why take so much time squinting at such a faint, distant object when we're going to have a spacecraft fly by soon, making observations that are squillions of times sharper than what we can see from our Earth-based telescopes?

There are a couple of reasons. First of all, the flyby will capture just a small moment in time in the Pluto system -- there are observations planned to cover about eight months of one Earth year. But we already know that Pluto is a dynamic place, with an atmosphere and surface that has changed dramatically since we first started studying it. The flyby will give us a snapshot of Pluto, which will be fitted in to the context of decades of Pluto observations to help us understand this complicated system.

Another reason to be looking at Pluto now is to help plan New Horizons' observations. New Horizons may well discover even more moons as it flies past, but those discoveries will very likely be too late for any changes to be made in New Horizons' jam-packed science plan for the encounter. This happened with Voyager 2 -- that spacecraft discovered a great many moons in orbit around Uranus and Neptune, but there was no time to plan detailed, high-resolution observations of these new moons and change Voyager 2's commands in the midst of the once-in-a-lifetime encounter.

So thanks to Hubble, we know almost enough about Pluto's fourth moon early enough for New Horizons to make plans to observe it. And New Horizons has one of the sharpest-eyed cameras ever flown to deep space, LORRI, which has an angular resolution of 5 microradians. Let's say that the best they manage to do with New Horizons is to image P4 from a distance of 100,000 kilometers. (They will get closer than that, for sure, but New Horizons will be very busy near close approach and observations of P4 are probably lower priority than some of the other science they've already got planned for that time.) That would give them half-kilometer resolution -- even if P4 turns out to be only 20 kilometers across, you'd still get 40 pixels. Not bad. It's enough to turn little P4 from a tiny, fuzzy point of light into a place.

More Hubble observations are still necessary so that Showalter and his coworkers can pin down the orbit more precisely. They have to be able to predict exactly where P4 is going to be when New Horizons flies past it in 2015, and that takes very precise predictions indeed. More work is always needed!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth