Emily Lakdawalla • Feb 18, 2011

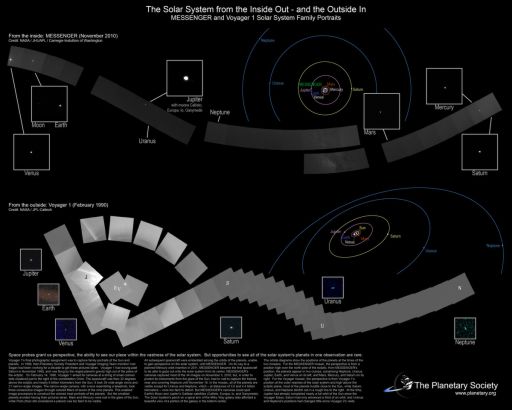

The Solar System from the Inside Out - and the Outside In

Space probes grant us perspective, the ability to see our place within the vastness of the solar system. But opportunities to see all of the solar system's planets in one observation are rare. In fact, there's only been one opportunity on one mission to see the whole solar system at once, until now.

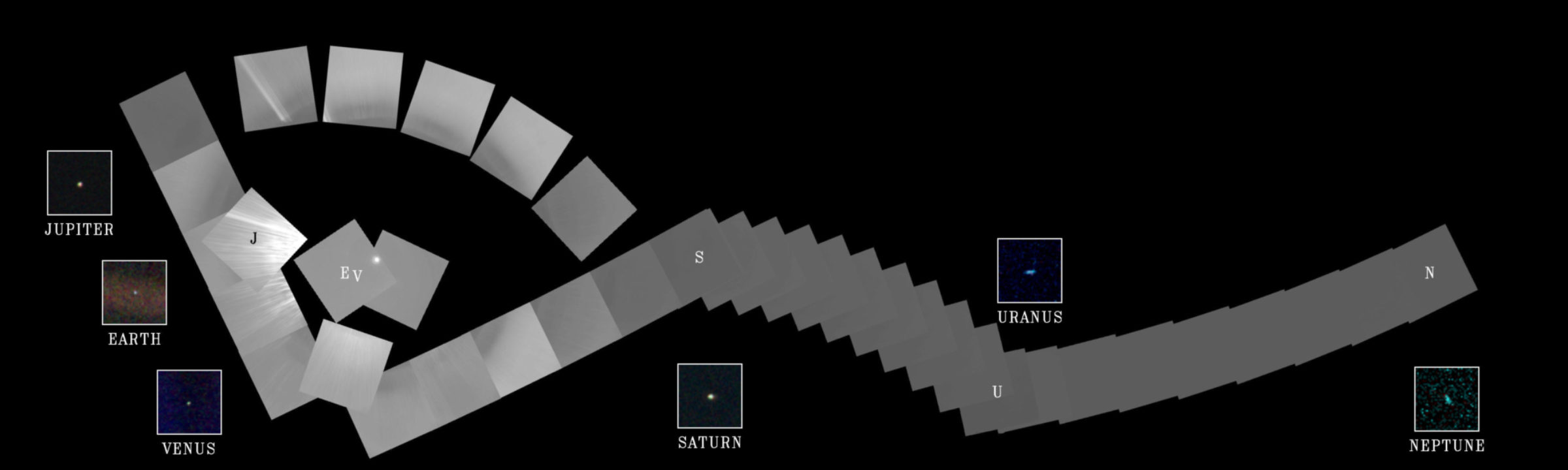

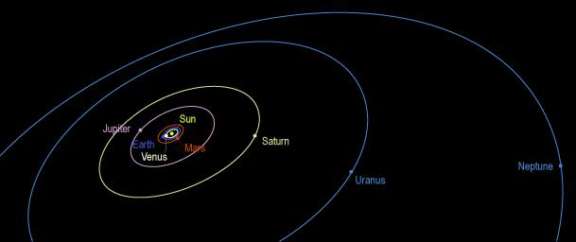

Voyager 1's final photographic assignment was to capture family portraits of the Sun and planets. In 1990, then-Planetary Society President and Voyager Imaging Team member Carl Sagan had been working for a decade to get these pictures taken. Voyager 1 had swung past Saturn in November 1980, and was flung by the ringed planet's gravity high out of the plane of the ecliptic. On February 14, 1990, Voyager 1 aimed its cameras at a string of small colored dots clustered just to the right of the constellation Orion. The spacecraft was then 32 degrees above the ecliptic and nearly 6 billion kilometers from the Sun. It took 39 wide-angle views and 21 narrow-angle images. The narrow-angle camera, with a lens resembling a telephoto, took three consecutive images through colored filters of seven of the nine planets. This enabled image processors at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to construct the colored inset portraits of the planets. But the smallest planets avoided having their pictures taken. Mars and Mercury were lost in the glare of the Sun, while Pluto (then still considered a planet) was too faint to be visible.

To help you visualize where the planets were in their orbits at the time this photo was taken, I made a little diagram:

All subsequent spacecraft were embedded among the orbits of the planets, unable to gain perspective on the solar system, until MESSENGER. On its way to its planned Mercury orbit insertion next month, MESSENGER became the first spacecraft to be able to gaze out onto the solar system from its center. MESSENGER's cameras captured most of the 34 images on November 3, 2010, but, in order to protect its instruments from the glare of the Sun, had to wait to capture the frames near and covering Neptune until November 16. In the mosaic, all of the planets are visible except for Uranus and Neptune, which -- at distances of 3.0 and 4.4 billion kilometers -- were too faint to detect. But MESSENGER's cameras could spot Earth's Moon and Jupiter's Galilean satellites (Callisto, Europa, Io, and Ganymede). The Solar System's perch on a spiral arm of the Milky Way galaxy also afforded a beautiful view of a portion of the galaxy in the bottom center.

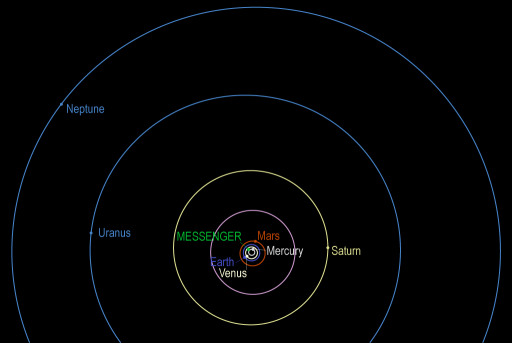

From its vantage point in the interior of the solar system, MESSENGER was quite a bit closer to most of the planets than Voyager 1 was. What's more, the planets and their moons all appeared in gibbous or full phase, making them much brighter to MESSENGER than to Voyager 1, which saw most of the planets, except for Jupiter, half-lit at best. Here's a top-down view on the solar system showing you MESSENGER's position with respect to all the planets:

Emily Lakdawalla

Positions of the planets during MESSENGER's solar system family portrait

The perspective is from a position high over the north pole of the ecliptic; from MESSENGER's position, the planets appear in two clumps, comprising Neptune, Uranus, Jupiter, Earth, and Venus on its left, and Mars, Mercury, and Saturn on its right.Both of these images just beg to be printed as posters and hung on the wall. So I've composed a poster containing both portraits and the orbital diagrams, which is now available from the Planetary Society store.

Read here an article by Charlene Anderson on the Voyager family portrait, from which I took some of the text for this blog entry. Read more about the MESSENGER family portrait at MESSENGER's website.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth