Emily Lakdawalla • May 13, 2010

Update on Voyager 2 status

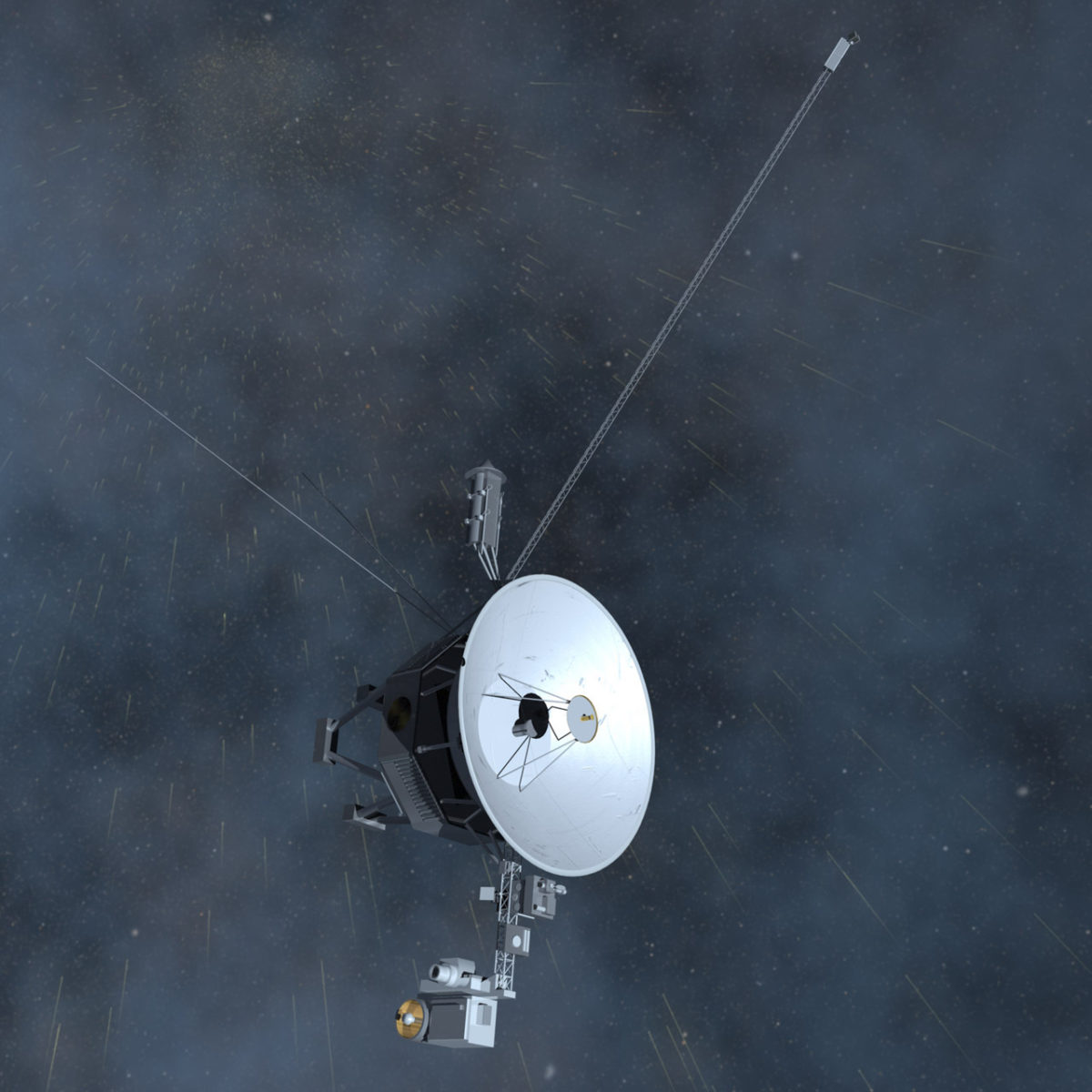

Good old Voyager 2; she takes a licking and keeps on ticking. I just had a chat with project scientist Ed Stone, and he's "optimistic" that they'll fix her problem and get her back her usual work of returning data from beyond the edge of the solar system.

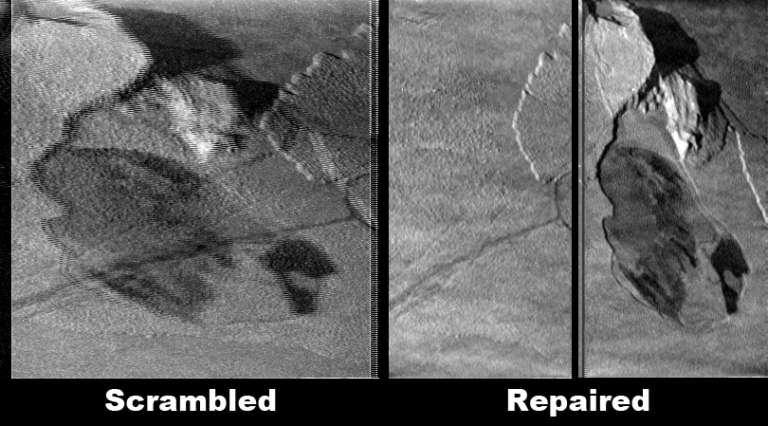

The mission has zeroed in on a flipped or bad bit in the flight data system being the likely culprit for the spacecraft's current problem with formatting science data properly. Remember that computers store information as strings of ones and zeroes or "on" and "off" bits. Once in a while, a passing cosmic ray can evade the radiation protection on a spacecraft and slam into a memory bit; when that happens, the bit may change value, from zero to one or vice versa. It's a lot like a transcription error in DNA; it's a sort of mutation of the code. It's possible that the flipped bit will have no or insignificant effect on the spacecraft, but once in a while, a flipped bit happens in a very important location and causes serious problems, and that's what the Voyager team thinks happened within Voyager 2's flight data systems.

(An aside: thinking the "mutation" analogy further, I wonder if there's ever been a cosmic-ray-induced beneficial mutation in flight software? I guess it'd be hard to know, in that the way we learn of these problems is when things go wrong; we'd be unlikely to notice if things continued to go right. Beneficial mutations are much, much rarer than harmful ones, anyway, even in the biological world.)

In order to figure out for sure if a flipped bit is the problem -- and to determine how to fix it -- they have commanded Voyager 2 to read out its entire flight data system software, one bit at a time, at 1200 bits per second, so that they can compare it to what should be in spacecraft memory, and look for an errant bit. Ed told me that that software dump has been completed, and it's "just a matter of time to determine which bit is flipped." I asked him if they were totally confident that that was the cause of the problem, and he said, "We don't know, but all of the symptoms are there." The computer is doing everything they command it to; it's just something screwy within the flight data system.

Once they've identified the location of the bit, they still need to figure out what they're going to do about it. If it's a simple flip, they can upload a command that will reset it to its correct value. It's possible that the bit has just failed -- that location in the spacecraft's memory can't be flipped back and forth again. In that event, "we'll have to send a program to exclude that location," Ed said.

While researching the problem I learned (or, to be more precise, relearned something I'd forgotten) that Canberra is now the only Deep Space Network location that can "hear" Voyager 2, because the spacecraft has moved so far south in the sky. So we can only hear Voyager 2's transmissions when Australia can see her. I mentioned this to Ed and from his response I learned something that hadn't really sunk in before, which is that Voyager 2 is always transmitting. "It transmits 24 hours a day; it's better for the transmitter to leave it on, it's a nice stable condition," Ed told me. She continuously transmits data from five still-active science instruments, measuring "the solar wind -- the speed of the wind, density, temperature, the strength of the magnetic field and its direction; energetic ions that are accelerated in that region of space; we measure cosmic ray nuclei, and we measure radio waves that are generated in the nearby interstellar space," Ed told me.

I told Ed about all the reader comments I've been getting, expressing hope and concern for Voyager 2, and asked him how he reacted when he heard of the anomaly. "We've been through this before," he said. "I'm an optimist; as long as we're getting data and we're understanding the basic issues, there's a reasonable hope" for recovery.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth