Marc Rayman • Jan 05, 2010

Dawn Journal: Patiently Accelerating

Dear Dawnters and Sons,

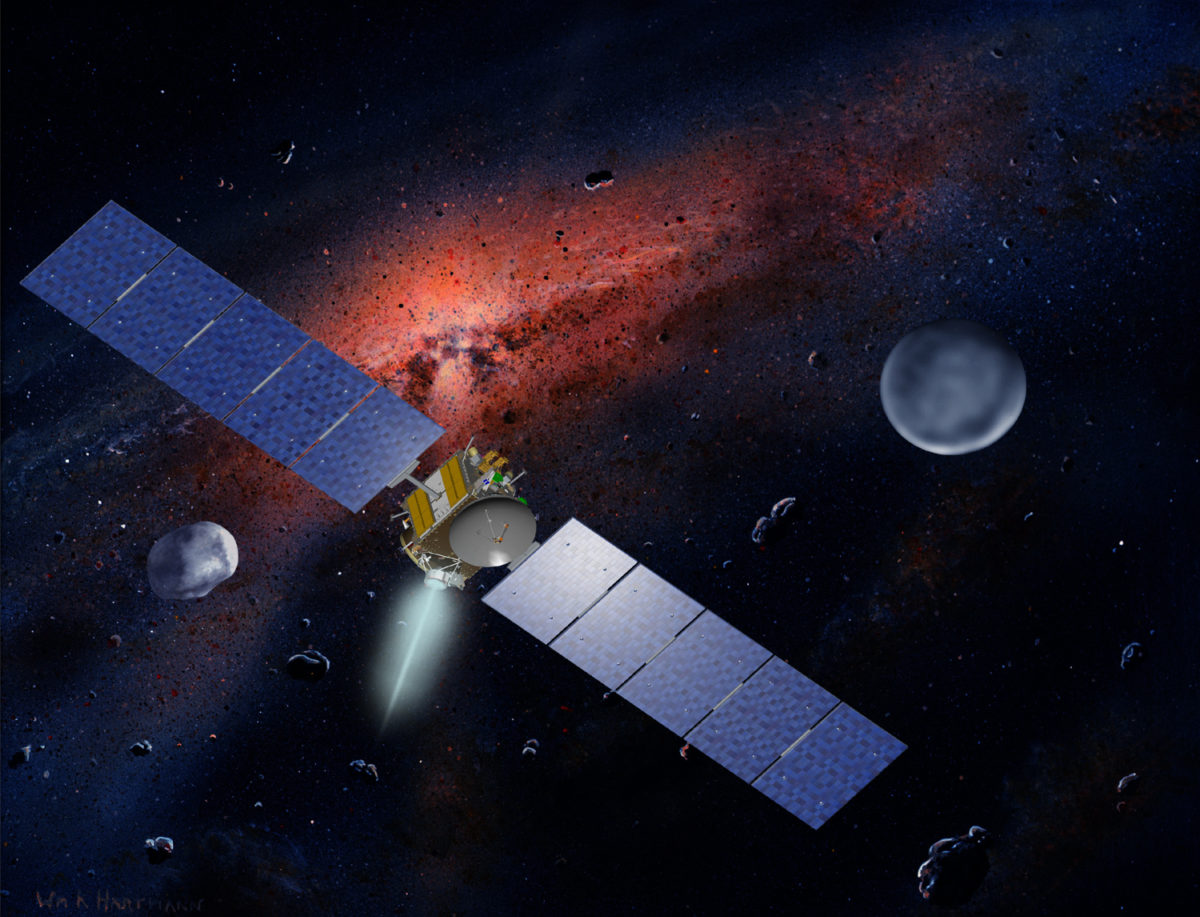

The Dawn mission continues to go smoothly, as Earth's distant envoy carries out its interplanetary journey. Although the craft still devotes most of its time to the slow but efficient reshaping of its orbit around the Sun to match Vesta's, controllers gave it some extra assignments since the last log to ensure its systems remain healthy and to prepare for its studies of Vesta.

Dawn usually interrupts ion thrusting once a week for about eight hours to point its main antenna to Earth. On November 30, however, instead of resuming thrusting, it dutifully followed different instructions that were stored onboard.

The spacecraft began the five days of special activities by activating the gamma ray and neutron detector (GRaND). Despite its name, GRaND is not at all pretentious, but its capabilities are quite impressive. It will reveal the atomic constituents of the surfaces of Vesta and Ceres. GRaND's measurements of space radiation this month showed it to be in excellent health. After a week of smooth operation, it was deactivated on December 7.

The visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIR) and the primary science camera also were turned on for the first time in more than half a year. As these sensors yield complementary data, controllers want to refine earlier measurements of exactly how their views overlap. This will allow scientists to correlate observations from the instruments in order to glean as much as possible about the nature of the protoplanets the craft will orbit. Dawn rotated to point at a star and then observed it simultaneously with VIR and the camera. By measuring precisely where the star registers in each device, their relative alignments can be pinned down. Upon completing the sequence of commands to acquire the desired data, the spacecraft turned to point its main antenna to Earth again and began transmitting the results during the next scheduled session with the Deep Space Network a few hours later.

The VIR team quickly discovered that a subtle incompatibility between certain instructions in the program for recording the signals from the star caused its shutter to remain closed. (VIR also has a reusable protective cover, but that operated as intended.) The unit continued to function and stayed healthy, but it did not perform the planned observations. The science camera imaged the target, but the purpose was to compare where the star appeared in the two instruments. The VIR commands are easily corrected, and the calibration will be executed again early next year.

Earlier this year, engineers developed new software for the science camera to improve its efficiency in mapping the distant worlds Vesta and Ceres. The software was updated once before in space, and the process followed this week was the same. As last year, loading software into the primary and the backup cameras was performed as entirely separate activities; each camera was off while the other was being upgraded. This was the only major work this week that was not accomplished with commands that had previously been stored on the spacecraft. After the new software was installed, each camera was directed to carry out a set of tests, and the results confirmed that both were operating correctly.

Among the other tasks this week was an annual evaluation of the backup star tracker, a device that recognizes star patterns so the spacecraft can calculate its orientation. To verify that the tracker remained healthy, the unit was powered on and operated. It correctly took pictures, identified the stars, and then determined the direction it was pointed. The tests verified that the unit remains in good condition and ready to be called into service in the unlikely event a problem with the primary tracker occurs.

On December 4, after completing all of its scheduled activities for the week, Dawn turned once again to point ion thruster #1 in the direction needed for propelling itself to Vesta, and resumed emitting high-speed xenon ions. It has continued since then with its familiar schedule of quiet cruise.

As the effect of the thrust continues to build up, tomorrow Dawn will pass another milestone. The thrusting since the beginning of the mission will have achieved the equivalent of accelerating the spacecraft by 2.00 miles per second (3.22 kilometers per second, or 7200 miles per hour). This is well in excess of what most spacecraft accomplish with their propulsion systems but is less than 1/3 of the planned maneuvering for the mission. To achieve this extraordinary velocity, Dawn has expended less than 126 kg (278 pounds) of xenon propellant during 474 days of powered flight. While the day-to-day change is small (as we will discuss in greater detail in February), with 24 hours of thrusting yielding just 7.2 meters per second (16 miles per hour), the benefit of its acclaimed patience is becoming evident.

As we have discussed several times (see, for example, this previous log), Dawn's actual speed has not changed by the values just presented. In the complex orbital dance it performs, partnered principally by the Sun but with others joining in as well (Mars being the most significant this year), the more it thrusts and climbs away from the Sun, the slower it travels. Nevertheless, the equivalent change in speed (that is, the change that would be achieved in the absence of the complications from being in orbit) is a handy measure of the effect of any spacecraft's maneuvering.

While Dawn continues pushing away from the Sun and deeper into the asteroid belt, the distance to Earth is still declining, as it has been since November 2008. The separation between the planet and the probe varies just as the distance between the tips of the hour hand and minute hand increases and decreases every hour. That suggests that it's time once again to refer to one of the clocks available in the Dawn gift shop on your planet. (If you didn't get around to preparing for the recent festivities marking the universe's reaching its present age, don't despair. Although there are only 5 trillion shopping days until the next such gala celebration, Dawn gift shops in most galaxies are offering attractive discounts right now.)

To picture the changing alignment, let's recall the clock described 365 days ago, with the Sun at the center. Dawn is at the tip of the minute hand and Earth is at the tip of the shorter hour hand. One year ago today, the celestial alignment corresponded to the position of the hands at about 6:01:45. At that time, Dawn was 2.49 astronomical units (AU) from Earth. In the intervening year, Earth has completed one orbit around the Sun, returning to where it was. Having traveled more slowly, Dawn is in a different position now that happens to be much closer to Earth. Today the alignment is similar to that at 6:30:00. Even though Dawn is farther from the Sun today than it was a year ago (as if the length of the minute hand had increased), in its current location around the clock face, it is 0.84 AU from Earth, only a third of what it was at the end of last year. The cosmic hands will continue to move into still-closer alignment until late next month, when the Sun, Earth, and Dawn will lie nearly along a straight line.

Picturing Dawn's position relative to Earth and the Sun may help some readers gain perspective on the explorer's interplanetary journey, and we will continue to present such illustrations (at least as long as the increased revenue for the gift shop makes it profitable to do so). Nevertheless, it is worth bearing in mind that from Dawn's perspective, the location of Earth is of little importance (except when it needs to point its antenna there). The ship travels on its own course around the Sun, independent of the motions of the distant celestial port from which it set sail more than 2 years ago. Dawn's sights remain firmly fixed on the destinations ahead, where it seeks to unlock secrets about the dawn of the solar system.

Dawn is 0.84 AU (125 million kilometers or 78 million miles) from Earth, or 345 times as far as the moon and 0.85 times as far as the Sun. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 14 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

6:30:00 pm PST December 30, 2009

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth