Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 29, 2009

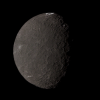

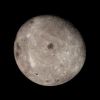

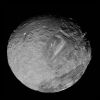

Planetary Society Advent Calendar for December 29: Rhea

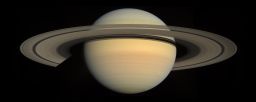

Rhea? You might be asking. Rhea? When Saturn has so many more interesting moons? Hear me out. Rhea has a bad rap; it's the second biggest of Saturn's moons, but there is nothing obviously impressive about it. No atmosphere like Titan; no geysers like Enceladus; not even any big geomorphic features like the chasm on Tethys or the huge impact crater on Mimas. It's just a round, tan ball of ice pretty evenly covered with craters.

But Rhea is a whole world, a unique one with its own story. That story is admittedly difficult to read, but there are clues. One clue is in the shape of its craters. Examine a picture of Rhea up close and you'll see that the craters aren't perfectly round; many are square or even hexagonal in outline. What could make craters straight-sided? There's something to the structure of Rhea's crust that makes it want to fracture more in certain directions than it does in others. Then, of course, there's the possibility that Rhea -- so far, alone among all the moons in the solar system -- might be accompanied by satellites of its own, as many as three rings' worth of cobbles and boulders orbiting the moon's waist. But the rings are too sparse and dark to see -- we have so far only detected Rhea's rings indirectly, if they actually exist.

Someday, far in the future, when humans (or, dare I suggest it without sounding utterly silly, robots serving as humans' avatars) can jet about the solar system with as little care as we now drive around the countryside, I imagine there will be some planetary scientist who will finally take up the challenge of figuring out what makes Rhea tick. Perhaps she's a graduate student, or a postdoc (if they have such things any more in this distant future), looking for some corner of the solar system that hasn't been explored to death yet. She'll land on Rhea and enjoy the side view of Saturn and its rings before getting down to business examining the microstructure of Rhea's crater walls, trying to understand why Rhean crust breaks the way it does. For a lark, she may fly high above the surface of Rhea, half its diameter high, trying to find and catch one of its elusive ring particles, those rarities, the moons of a moon.

Each day in December I'm posting a new global shot of a solar system body, processed by an amateur. Go to the blog homepage to open the most recent door in the planetary advent calendar!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth