Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 07, 2009

Saturn's equinox: Daphnis' shadow and wake

There are two major things that I was sorry not to be able to write about during my maternity leave. One of them is the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter launch and first images, and the other is the approaching equinox at Saturn. LRO I'll have to return to later, but Saturn's equinox is right around the corner, on August 11 -- it's time to focus on that!

Saturn's equinox is a Really Big Deal. It's such a big deal that the Cassini Saturn orbiter two-year mission extension is titled the "Equinox Mission." Why is the equinox such a big deal? Let me step back and make sure we're all on the same page about what the equinox means, and then I'll show you the eye candy that results from Saturn's equinox.

Like Earth, Saturn rotates on an axis that's tilted to the plane in which it orbits the Sun. So, as it goes around the Sun, Saturn has seasons. When the south pole of the rotation axis is pointed in the general direction of the Sun, as it was when Cassini arrived there in June 2004, it's summer in the southern hemisphere and winter in the north. The south pole of Saturn, and all of Saturn's moons, received continuous sunlight, and the north poles were in permanent night. And the southern face of Saturn's rings was in permanent sunlight (except when they passed through the shadow of the planet), while the northern face of the rings was dark except where the rings were transparent to sunlight.

Cassini arrived a short while after Saturn's southern summer solstice, the day when the Sun made its farthest southern excursion. Since then, as Saturn has proceeded in its stately 30-Earth-year orbit around the Sun, Cassini has watched sunlight move slowly northward. Northern lands on the planet and moons have been seeing sunlight for the first time in years, and the Sun is setting on the southern poles. In high summer, with the Sun far to the south, the rings cast huge shadows on Saturn's northern hemisphere. As summer waned and the Sun moved northward, the ring shadows have moved southward and grown thinner and thinner.

On August 11, 2009, the Sun will pass through Saturn's equator. For a brief moment, both poles will be sunlit, and the shadows of the rings will collapse to a thin line cast across the waist of the planet. This is the equinox. After the equinox, the south poles of Saturn and its moons and the southern face of the rings will be in shadow, while the north poles and north side of the rings will be in sunlight. For the first time, Cassini's cameras will get good looks at the north poles of the moons.

But what is especially exciting about the time period around equinox is the behavior of the rings. The rings are almost unimaginably flat. Although they're roughly twice Saturn's diameter, about 120 thousand kilometers across, they are in most places less than a tenth of a kilometer thick (and in some places, only 10 meters, that is a hundredth of a kilometer, thick). As the Sun has crept northward, it has been striking the rings at a lower and lower angle. (Thanks, by the way, to Dave Seal for sending me a handy-dandy table of solar declination angles for Saturn.)

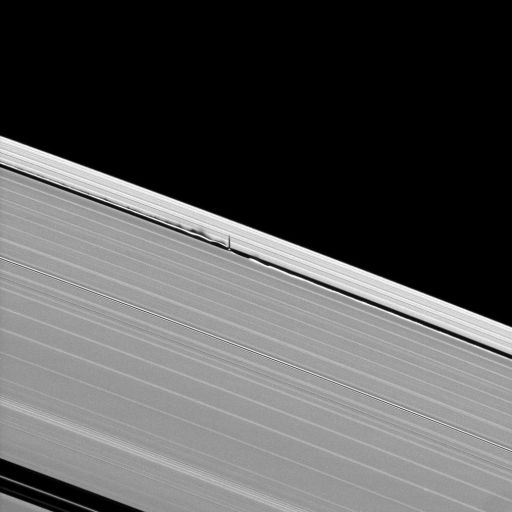

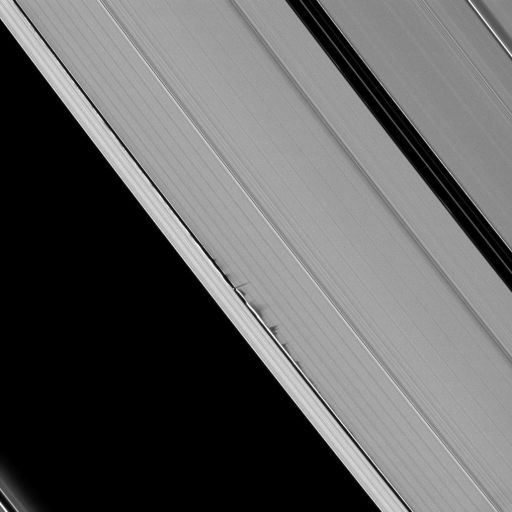

The unimaginable flatness of the rings means that there's no topography to cast shadows. Or almost no topography. But during the special time around the equinox, as the Sun strikes the rings at angles approaching zero, tiny lumps and bumps within the rings begin to make themselves known as their exceedingly subtle topography begins to cast shadows.

The first time that those of us who watch Cassini through its raw images noticed shadows being cast within the rings was in early April, when the solar declination was just under 2 degrees. At that angle, the shadows being cast are roughly 30 times longer than the height of the features casting the shadows (assuming, that is, that the rings are perfectly horizontal). I wrote about that on April 13.

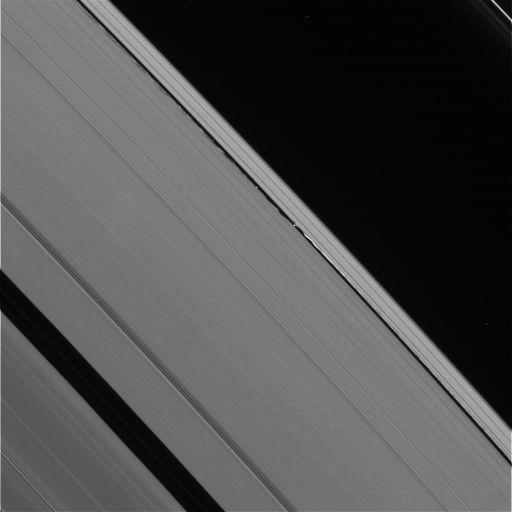

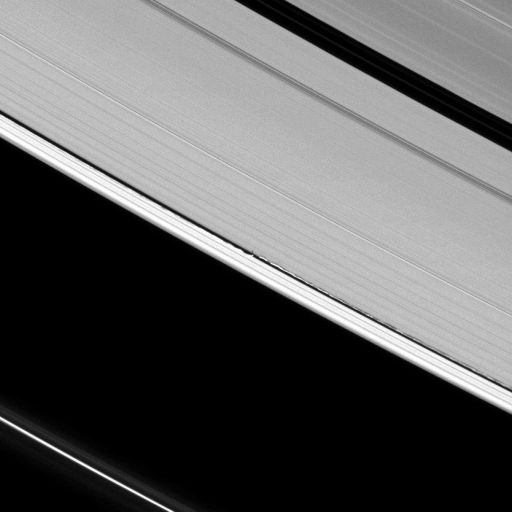

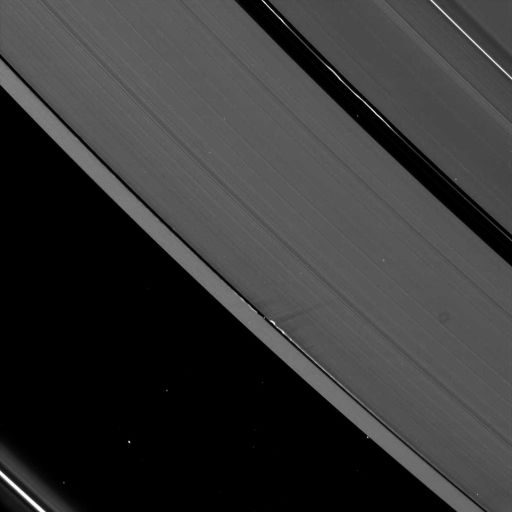

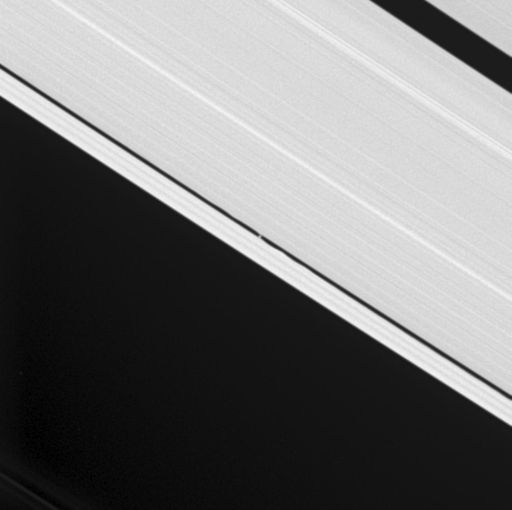

One of the best places to watch these shadows develop is in the Keeler gap, the division near the outer edge of the A ring that is carved out by the tiny moon Daphnis. The Keeler gap mostly has pretty straight sides, but just in front of and behind the orbit of Daphnis it has a noticeably scalloped structure:

NASA / JPL / SSI

Daphnis, the 'Wavemaker Moon'

Among the moons discovered by Cassini is Daphnis, formerly known as S/2005 S1. Daphnis orbits within the narrow Keeler gap at the outer edge of Saturn's A ring, exciting waves in the edge of the gap. This image was taken on August 1, 2005, from a distance of 853,000 kilometers.Things began to change in January. In the image below, you can see Daphnis casting a shadow on the A ring, and there's just the barest hint that its scalloped wake has a shadow too. According to Dave's table, on this date the solar declination was just under 3 degrees; shadows are about 19 times longer than the objects casting them. If nothing else, that fact tells me that Daphnis is probably saucer-shaped, like Atlas, since it's a couple pixels wide in this photo and yet its shadow is only maybe 8 pixels long. If it were a sphere its shadow should be more like 40 pixels long.

There are a whole lot of other exciting things to see in Cassini images during this equinox season. Shadows of moons falling on rings, weird lighting effects on the rings, shadows cast by previously undiscovered structures within the rings. I hope to focus on all these topics over the next week. Stay tuned! And in the meantime, you can explore all the weirdness at Saturn by checking out the raw images, posted more or less as they come down from Saturn to JPL's Cassini raw images website.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth