David Seal • Jun 04, 2009

Canto III: Hints of Equinox

Dante observes the fourth circle where the avaricious and the wasteful battle over control of large stones, knocking them and themselves together, within a great gloomy circle.

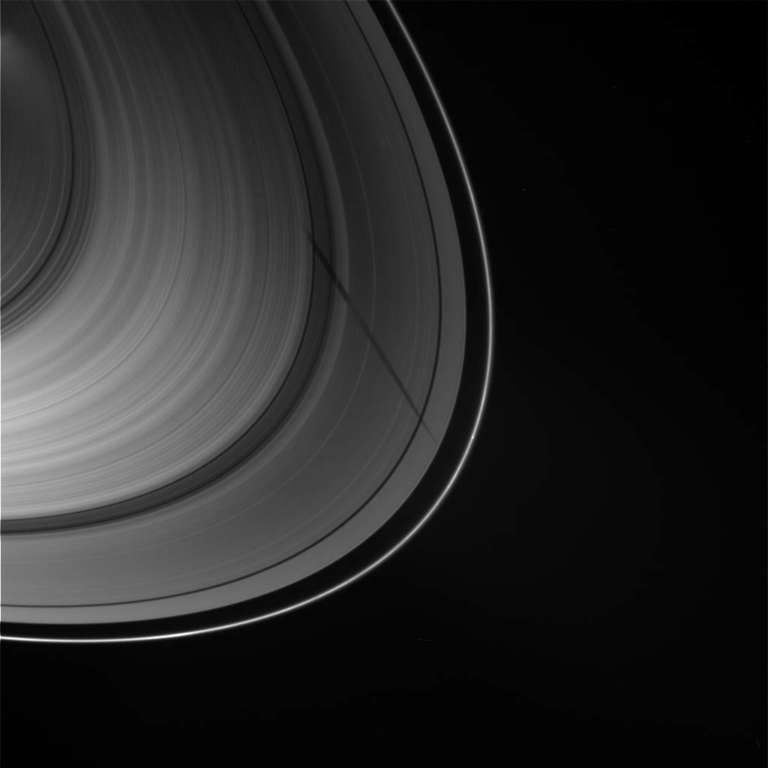

Saturn is rapidly approaching equinox, where the Sun passes through the ring plane (south-to-north, i.e. the northern vernal equinox), and its ring system (i.e. its great now-gloomy poorly-lit circles of large blocks of water ice) is starting to show some really interesting behavior. Emily commented on this about six weeks ago, where she (and the folks from unmannedspaceflight.com) spotted shadows cast by clumps at the outer edge of the B ring. We drooled over these images at JPL just as much as the public did.

This time period is unique for Cassini, since equinoxes only happen twice per Saturnian year, or once about every 15 Earth years. Another reason why NASA's approval of our first mission extension was a good decision, since it enabled observations of the rings at extremely low illumination angles. The exact date of equinox is August 11, but even now, two months before, there's a lot to look at already.

It is amazing to consider that Saturn's main ring system averages a few tens of meters in thickness, but spans a planar distance of about 275,000 km. That's a phenomenal aspect ratio of about 10 million+, or about four thousand times thinner than a piece of paper (compared to its length). Inconceivable! However, there is topography within the rings from a number of dynamical forces, and likely a large number of embedded, undiscovered moonlets larger than its average thickness, and this is what we're after. As the Sun gets closer to the ring plane, more of this stuff is going to become visible. (These features have been there the whole time; they're not caused by the equinox - we just haven't been able to see them yet.) So exciting.

Emily did some good calculations on the likely sizes of the shadow-casting clumps of material at the outer edge of the B ring - and she was correct in stating that these are almost certainly clumps of "stones", not individual bodies. The only things I can add to her post is that it is quite plausible that this ringlet is inclined, since it's in a resonance with Mimas, and Mimas is inclined. So those clumps could be slightly out-of-plane and that could have contributed to the casting of shadows in addition to their overall size. There is other evidence of this explanation as well, since it doesn't appear everywhere. Naturally, it wouldn't appear past 90 degrees phase, since the shadows would be cast along the ringlet or out into darker territory, and the shadows might not be visible through to the unlit side of the rings, but there are other images before and since of the lit side at low phase angles where this doesn't seem visible (to me) - perhaps because the ringlet's clumps are smaller, or because the ringlet isn't out-of-plane, or both.

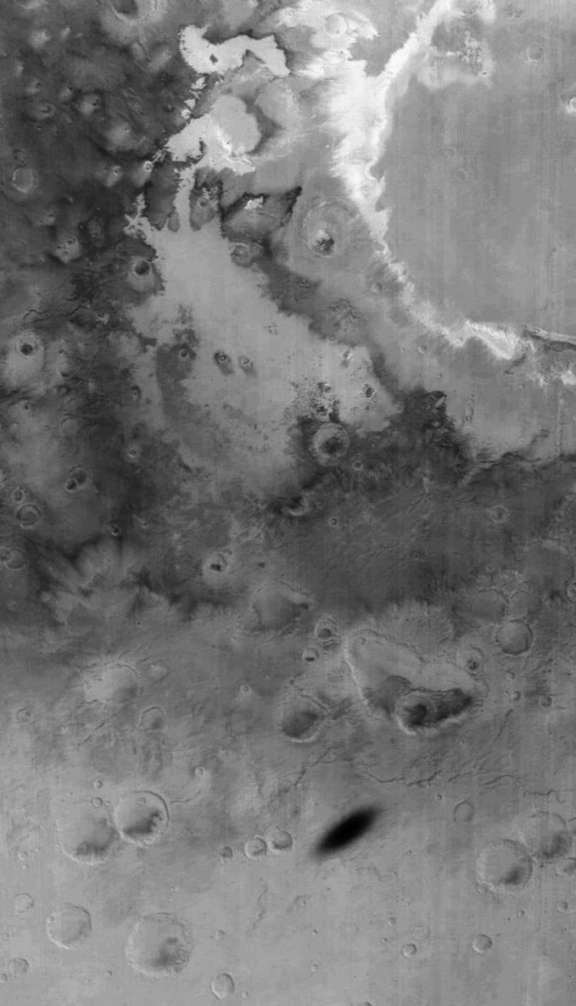

One of the images that immediately followed this one really threw us for a loop for a while. It shows the shadow of a moon on the rings, but the shadow doesn't seem to take hold everywhere. Explain that - how do some parts of the rings seem to defy the laws of physics and "ignore" the eclipsing body??? I stared at this off and on for a day or two and finally came up with a reasonable explanation (which everyone else seemed to come to as well).

It all unlocks when you realize that we're looking at the unlit side of the rings. In other words, the shadow is being cast on the *other* side. The other piece of the puzzle is that Saturn's rings are now being illuminated nearly equally by the Sun, PLUS reflected sunlight from the northern and southern hemispheres of Saturn. So what's happening is that the shadow isn't getting through the dense parts of the rings here, and those rings (because they're dense) are being illuminated by reflected light from Saturn (the hemisphere on our side, i.e. the northern one) - so they seem to defy the laws of physics. The less dense portions of the ring is where the shadow penetrates, i.e. nearly all particles in the ringlet are shadowed (not just the surface of the "other side"). Since those ringlets are less dense, they reflect less light overall from the northern hemisphere so they look darker. Make sense?

The next picture illustrates this a bit more clearly via another moon shadow and a larger part of the rings. Again here the shadow is on the "other side" of the rings. We know the B ring is very dense, so naturally the shadow disappears from view there as the dense ring blocks it off. But this ring still reflects light from Saturn, so it appears brighter. Notice how the brightness of the B ring varies so much in longitude. This is due quite clearly from the fact that different longitudes see different proportions of the illuminated northern hemisphere. As you get closer to sunward side, the rings see more illuminated planet, so they're brighter. (No doubt there's also more complex phase function at play here.)

There's some other great stuff to be had. Next we have a look at Daphnis (discovered by Cassini!) in the Keeler gap. Its wakes clearly have vertical structure here, and are casting really tremendous shadows onto the rings. I'm sure there's a lot of good science to be had by deconvolving the vertical shape of the waves from the shadow detail. Daphnis is so appropriately named, to me, since he was not only a shepherd but a player of the pan pipes - not unlike the musical mischief the moon is creating on the rings.

Before I finish I can't help but mention Prometheus, which is beginning to make deeper plunges into the F ring, causing its own mischief, on a considerably grander scale than Daphnis, as you can see from our next picture. Streamers from Prometheus' previous invasions (one orbit earlier, each) are clearly visible. Prometheus' invasion peaks later this year, in November. This is not associated with equinox but is another very rare event - once every 13 years - and therefore another good opportunity afforded to us by the equinox mission to learn more about the Saturnian system.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth