Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 26, 2008

Phoenix sol 30 update: Alkaline soil, not very salty, "nothing extreme" about it!

Or: "pHoenix!" (Sorry. MECA team leader Michael Hecht is responsible for that joke.)

There was a teleconference on the status of the Phoenix mission up to sol 30 today. (Like all of these media teleconferences, if you'd like to listen to it after the fact you can do so at JPL's Phoenix Media website.) Here's the news in a nutshell:

- The wet chemistry lab analyzed its first sample, and reported the pH of the surface soil to be alkaline, at between 8 and 9. This was a big surprise to most people.

- The wet chem analysis is about 80% complete. Preliminary results show the presence of cations like magnesium, sodium, and potassium, and anions like chloride. They've not finished the analysis for sulfate yet. Preliminary results indicate it's salty but not extremely so, with salt at the few hundred to a thousand part-per-million level. (The salinity of surface water in Earth's oceans is roughly 35,000 ppm; 1,000 ppm would rate as very slightly brackish.)

- Overall, there is "nothing extreme" in the first wet chemistry lab sample results, which is good news for the question of whether Mars is or ever was habitable.

- TEGA has completed its analysis of its first soil sample. There was no actual water present in it -- no surprise there -- but water vapor was given off at the highest temperatures, indicating water bound within minerals. Examples of minerals on Earth that contain bound water include things like gypsum, clays, and opal, and are generally formed by chemical alteration of other minerals in wet environments of one kind or another. The TEGA team does not yet have an identification for the mineral(s) that released this bound water.

- The TEGA team expressed confidence in their ability to deliver a sample through the narrowly open slit on oven #5.

- There was an earlier press release indicating that the lengthy (hour-long!) shaking of TEGA oven #4 may have caused a short circuit within that oven. This does not harm any of the other ovens, and since the analysis in oven #4 is now complete, it clearly didn't harm that oven. The TEGA team will attempt to avoid a situation in which they have to do an hour's worth of shaking in the future; a few minutes should be sufficient to get a sample into oven #5.

- There is no answer for the question of how TEGA could have been sent to Mars with doors that don't open properly. The Phoenix team is, appropriately, focusing its efforts on making TEGA work now, as is; there will certainly be an investigation of how it arrived at Mars with the door problem undiagnosed, but that effort has not yet started.

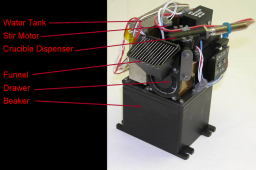

Today was all about the wet chemistry laboratory, which is half of the MECA instrument, which itself is one of the two instruments that are really unique to Phoenix (the other being TEGA). Nothing like the MECA wet chemistry analysis has ever been performed on Mars or, for that matter, any other place except Earth. Here's how MECA's wet chemistry laboratory -- which I'll abbreviate "WCL" for this post because I'll be saying it so often, but I'll try not to make a habit of it -- works.

First of all, here's a shot of MECA with the scoop poised over it on sol 30, just before the sample was delivered.

NASA / JPL / UA / Texas A & M

Phoenix prepares to deliver first wet chemistry lab sample

On sol 30 at 09:55:56 local time, Phoenix was ready to deliver a sample from the site called "Rosy Red" within Wonderland to the first of four wet chemistry laboratory cells in the MECA instrument. MECA is the box on the left; you can count the four WCL sample chambers marching up the right side of the box. On the right side of each of the WCL sample chambers is a funnel with a grille over it. There is a great deal of dirt visible on the deck of the lander, to the right of and below MECA, including on the Planetary Society-provided DVD. Nearly all of that dirt landed there as a result of the large scoopful of soil that was delivered to TEGA (the box at lower right of the image) on sol 12, and the subsequent shaking that was necessary to get any sample inside it. The soil did not fall from the scoop, so could not have contaminated the wet chemistry laboratory funnels. There is also a pile of dirt on the top of MECA; this is spillover from the two (to date) sample deliveries to the other part of MECA, the optical microscope, whose sample slides are rotated into position to receive samples through the slit within the notch on the left side of the MECA instrument.

NASA / JPL / UA / MPI / animation by Emily Lakdawalla

Sample delivery to the first MECA wet chemistry cell

Two images captured by the robotic arm camera document the first delivery of a Martian soil sample into a MECA wet chemistry laboratory cell. The image taken at 12:29 shows the soil sitting in the funnel, which is covered by a grille whose wires are spaced 2 millimeters apart. At 12:35 the drawer underneath the hopper had closed, allowing a tiny amount of dark dirt to fall to the lander deck below. However, most of the sample remained stuck inside the funnel. Fortunately, plenty of sample did fall through the funnel into the waiting drawer of the wet chemistry laboratory cell. (For comparison, look at the next funnel, located at the top of the image; you can see right through it to the deck of the lander below.)There's a stirring stick in the beaker, so they stir it up to help stuff in the sample dissolve into the water. Spaced around the beaker are many sensors. From an abstract I found describing the instrument, here's a description of the sensors that are included:

The beaker assembly contains an array of sensors consisting of solid state and PVC (polyvinyl chloride) membrane based ion selective electrodes. These sensors will analyze for inorganic anions and cations, including calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, chloride, bromide, ammonium, nitrate, lithium, and sulfate. The array also includes special electrodes for pH, conductivity, oxidation-reduction potential (Eh), anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) for heavy metals such as Cu2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, chronopotentiometry (CP) for independent determination of chloride, bro-mide & iodide, and cyclic voltammetry (CV) for identifying and analyzing possible reversible and irreversible redox couples.

All clear? MECA team member Sam Kounaves reported that they completed about 80% of the analysis on the first cell. "It's been difficult and slow but it performed flawlessly yesterday," he said, which must have been a huge relief to the team. He went on to say that the team's biggest surprise was the pH being alkaline, with a pH of 8 or 9, rather than acid. (A pH of 7 is neutral.) He said they've also successfully measured magnesium, sodium, potassium, and chloride, though he wasn't yet prepared to give abundances; and he said they haven't finished the sulfate analysis yet, that that'll take another couple of days. He said they can't make a definitive statement about nitrogen yet. He said they "don't see extremely high salt," and that "calcium appears to be extremely low and the chloride appears to be low also. We have to wait for the rest of the analysis to see where the other anions are. There were reasonable levels of salt," hundreds to thousands of parts per million.

Clearly the reporters on the teleconference didn't quite know what to make of this news. The news does have bearing on that key question for the Phoenix mission, the habitability of the Martian environment. The fact that the soil sample wasn't strongly acidic or incredibly salty is good news for habitability. Strictly considering the chemical species that the wet chemistry lab was able to measure so far, it wouldn't be a terrible substrate to try growing some alkaline-happy Earth plants (such as asparagus or turnips or green beans) in. However, MECA can say nothing about whether there are any organics present in the soil -- that's TEGA's job. And MECA's analysis has limited sensitivity; there are a lot of trace elements it's incapable of measuring. But, within its limitations, the news is good for habitability.

In fact, Kounaves said, this looks a lot like soil you find near the surface at one of the locations commonly studied as an analogue to Mars: the Dry Valleys of Antarctica. He said that soil is also alkaline. However, he said, if you dig down 30 centimeters, to the ice table, you can find that the ice-soil interface somehow acts to concentrate a lot of the chemicals that MECA is searching for; he said that at the ice table you can switch to acid soils, and go from near-surface salinities of hundreds of parts per million to sub-surface salinity that's much closer to ocean water, 15, 20, even 30 thousand parts per million. (Again, surface seawater is around 35 thousand.) So it'll be really interesting to see what subsequent samples reveal.

On to the TEGA saga. A press release yesterday mentioned a new problem that was discovered after a sample was finally shaken into oven #4: "Four days of vibration eventually succeeded at getting the soil through the screen. However, engineers believe the use of a motor to create the vibration may also have caused a short circuit in wiring near that oven. Concern about triggering other short circuits has prompted the Phoenix team to be cautious about the use of other TEGA cells." Today, Barry Goldstein clarified this. He said that the short is confined to oven #4, which they're now done with; so the short has no direct effect on the other cells. It's just that the fact that it happened will make them more cautious about doing so much shaking in the future.

It's very, very, very good news from the TEGA team that, despite all the problems, they've successfully completed the analysis of the first sample: Bill Boynton said today that "the scientific data coming out of the instrument is just spectacular; the instrument is working very well in that regard." I think the team deserves congratulations for that. Apparently, reducing the data that they've received from this first analysis will take them weeks. What they can say so far is that the sample was pretty dry (no surprise, since it was from the surface and was hanging out in the sun and air over the TEGA oven for days until it got inside), but that there were small amounts of carbon dioxide and water vapor released during the highest-temperature heating cycle, which means those gases are bound up in the minerals in the rocks. He could say with some certainty that the soil had definitely interacted with water at some time in the past. What he can't say yet is whether that interaction happened at its current location or whether it happened elsewhere on Mars, and what they're looking at is soil that was blown in from elsewhere.

NASA / JPL / UA / animation by Emily Lakdawalla

Attempt to open TEGA door 5

Two images were taken of the TEGA instrument on sol 25, before and after an attempt to open the doors of oven number 5, adjacent to oven number 4, which had been opened previously and used for the first sample. The left-hand door of oven 4 never opened properly. It now appears that neither door on oven 5 has opened properly. The doors are not motorized; they are connected to springs and latches, and should spring open completely when the latch is released. There is no mechanism within TEGA to attempt to push the doors open any further. The springs on the doors are strong enough to push the doors open even when buried under a few centimeters of soil; you can see that the left-hand door has successfully thrown off nearly all the soil that covered it. So it is unclear what is preventing the doors from opening.I also asked about the numbering scheme of the ovens -- if the oven on the end is #4 of 8, why is the one next to it #5? The ovens are actually numbered 0 through 7, and not 1 through 8. The ones we're looking at now are 4, 5, 6, and 7. Oven #0 is directly opposite #4. Why would they do this? Probably because it means they only need three rather than four data bits to encode information in their data stream about which oven they're using: numbers 0 through 7 are binary 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, 111. They could call "000" oven number 8 if they wanted to, but it's easier just to translate directly from binary 000 to decimal 0, and binary 111 to decimal 7.

One of the cool things they mentioned today is that they've developed a new skill: they can now take one sample with the robotic arm and, by careful sprinkling, deliver material taken from one spot to all three of the analysis instruments -- TEGA, the MECA WCL, and the MECA microscope. That's not something they flew to Mars knowing how to do; the plans were always just to scoop and dump onto one instrument, then go get another scoop and dump onto the next instrument. But they had to develop the sprinkle technique to make TEGA work, and that's had the positive payoff that now they can analyze the same sample three different ways, so they know that what they measure in the WCL and TEGA is material that looks the same as what they're seeing in the microscope. Every cloud has a silver lining!

Finally, here's a neat view of that pesky, clumpy Mars soil, taken with the robotic arm camera, focused on a tiny fraction of the width of the tip of the scoop. This image has a resolution of 30 microns per pixel -- that is, 33 pixels make a millimeter! I didn't realize the robotic arm camera had this capability. It's like there's two different microscopes on Phoenix, one with low power magnification and one with high power. And there's still the Atomic Force Microscope to come (which I'm afraid I have not heard mentioned once in one of these telecons).

NASA / JPL / UA / Texas A & M / MPI

High-resolution view of soil in Phoenix' scoop

After scooping a sample of soil from the location called "Rosy Red" on sol 26, Phoenix rotated the tip of its scoop to within 11 millimeters of its robotic arm camera, which took a series of photos of the soil under the light of red, green, and blue LEDs to build up this picture of the fluffy, clumpy, red soil found at the Phoenix landing site. The actual image has a resolution of 30 microns per pixel; this version has been enlarged somewhat. The width of the metal tab in the robotic arm camera image is 15 millimeters.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth