Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 15, 2008

Things I think are cool in the first MESSENGER image of Mercury

OK, the baby's in bed and I have time to examine the new face of Mercury. To review: this is the first image returned from MESSENGER following its first flyby of Mercury, on Monday, January 14, showing a face of Mercury not seen by Mariner 10 (though it has been observed using radio telescopes). Originally, more images were expected today, but because of conflicts with the Deep Space Network having to do with anomalies on the Ulysses solar observing mission and elsewhere, MESSENGER lost some of its expected communications time. Because the image was received so late in the day Tuesday, when much of the world was already asleep, NASA considered holding its release until Wednesday morning; but it seems that the media have been so impatient to see it that, in an unusual move, they released it at 8 pm Eastern time today.

OK. Here's the image.

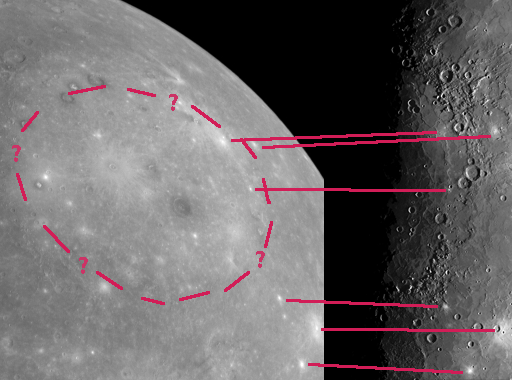

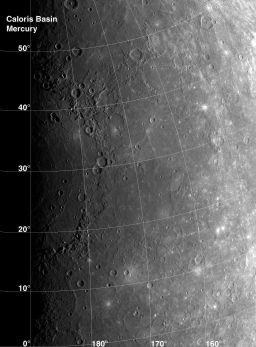

The apparent lack of very large basins on this face of Mercury surprises me too. Part of that has to do with how it's lit. The new MESSENGER image includes the entirety of the Caloris basin, only half of which was visible in Mariner 10 images, but despite being one of the biggest impact basins to be found anywhere in the solar system it is astonishingly difficult to see in the MESSENGER view because the Sun is nearly directly above it. Here's Mariner 10's view:

NASA/JPL/Mark Robinson

Mercury's Caloris Basin

The Caloris Basin is one of the largest basins in the solar system at approximately 1,300 kilometers (800 miles) in diameter. Only half of it was seen by Mariner 10 as it sped past Mercury in 1974. Source Color: Greyscale. Scale: 1000.00 meters per pixel. Created: 29 March 1974.One place it's easy to find topography is on the terminator, a term that still makes me giggle; for those of you not in the know, the "terminator" is the day-night boundary, where the sun slants onto Mercury's surface at a low angle, casting long shadows. Caloris was discovered in Mariner 10 images because it sat on the terminator, so the long dawn shadows accentuated the subtle topography along the multiple rims. I don't see any new large basins on the terminator in this photo, but I see something else that, as a structural geologist, I find just as exciting: rupes. "Rupes," the Latin word for "cliff" or "escarpment," represent areas where the crust of Mercury (or another world -- there are rupes on the Moon and on Miranda, for instance) has deformed under some kind of compressional stress. Here's the most prominent rupes I see. I've blown this cutout up by a factor of two:

NASA / JHUAPL / CIW

New rupes found on Mercury

On the terminator (day-night boundary) in the first wide-angle shot of Mercury returned from MESSENGER's first flyby are several steep scarps that cut across craters, like the one at the center of this photo. Such scarps are called "rupes" on Mercury and are places where the planet's crust has deformed, buckled, under compression.I'm getting sleepy so I'd better call it a night. The last time I talked to someone on MESSENGER it sounded like they probably got more than just this image in this evening's communications session, so I'm certain we'll see more images released tomorrow.

I will mention one last little item that only a true geek will love. The caption that the MESSENGER team released with the image did not include the exact time at which it was taken. However, you can figure out the time it was taken based upon its filename, "EW0108829708G." The filenames on the released Mercury images have the same form as the ones I've seen for MESSENGER images already released to the Planetary Data System: the filename has 13 characters, of the form "Eannnnnnnnnnp." What "E" means I'm not sure -- every file name begins with that, perhaps it indicates data from the camera instrument as opposed to any other instrument -- but the rest I can interpret. The character in position "a" is "N" for the narrow-angle camera and "W" for the wide-angle camera. The 10-digit number "nnnnnnnnnn" measures time, in seconds, counted up on the spacecraft clock. And the character in position "p" designates which color filter was used for the image (it's always "M" for narrow-angle camera images, where there are no color filters, but can be letters A through K for the 11-filter wide-angle camera; in this case, it's the G filter, a narrowband one at a wavelength of 750 nanometers, just over the edge of red into the infrared, which is, incidentally, very similar to the wavelength of the filter most often used by the rovers' Pancams for imaging rocks on Mars). Since I know the times of earlier images released by the MESSENGER team, for instance the one named "EN0108529741M" that was taken on January 11 at 09:06, I can figure out from the name of this file that it was taken 299,967 seconds later, which happens to be on January 14 at 20:25. Piece of cake.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth