Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 20, 2006

They released the entire Cassini RADAR swath across Xanadu!

Following immediately on the heels of the release of the "T7" swath to the Planetary Data System, the Cassini RADAR team has delivered more: yesterday they released the entire "T13" swath, acquired in April, to the public. And there'll be new RADAR data acquired this Saturday. It's a RADAR bonanza! This makes "T8" the only swath of RADAR data that hasn't been completely released; and the RADAR team has already given out most of that swath in bits and pieces. You can see all of these swaths on my Cassini RADAR Images of Titan page. Now let's dive in to T13; this swath shows some really incredible stuff.

Here's the amount of the T13 swath that had been available to view before yesterday:

![Cassini RADAR swath on Titan, flyby T13, April 30, 2006 [DEPRECATED]](https://planetary.s3.amazonaws.com/web/assets/pictures/_2400x282_crop_center-center_82_line/20170910_titan_radar_t13_32px-deg_temp.jpg)

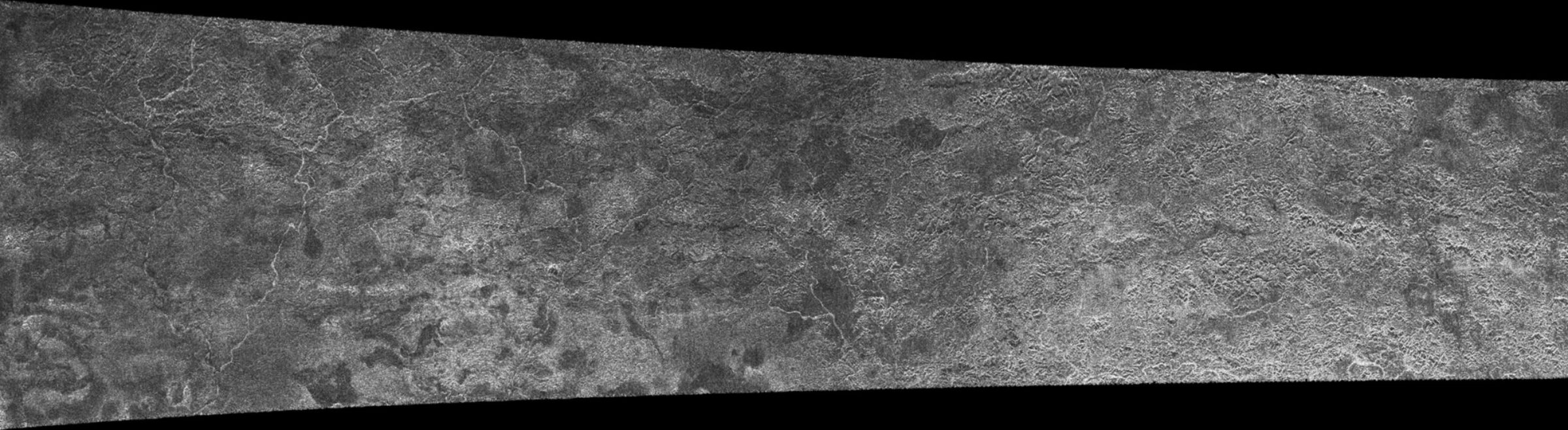

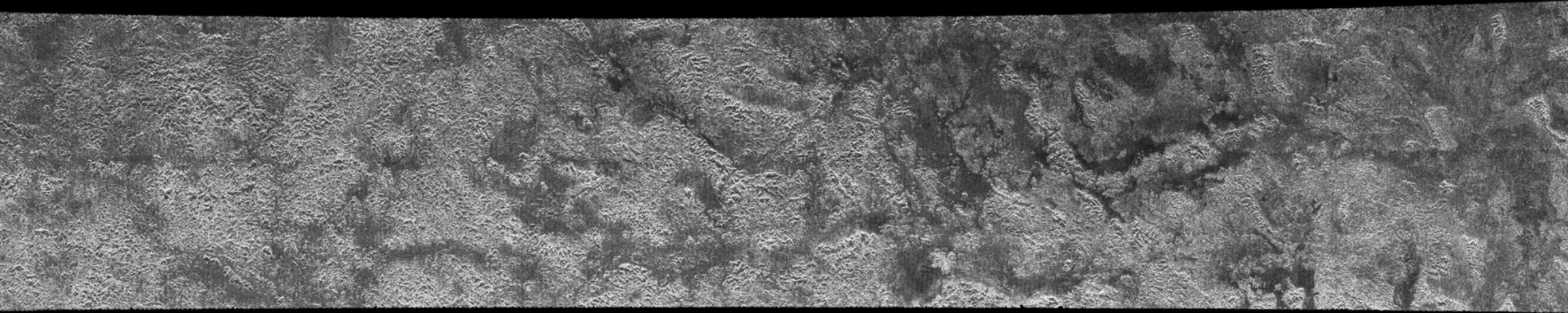

And here's the whole shebang:

If you click to enlarge above you'll get the view at a resolution of 1,400 meters per pixel. But the RADAR instrument is capable of much better than that. Here it is at 350 meters per pixel (once you click; each piece is about 1 MB in size). There's so much to see here...I'll point out a few of my favorite spots below.

I talked about some of the features, including channels and impact craters, visible in this swath in a May article based on an interview with Ralph Lorenz. In the previously unreleased parts of this swath, there are lots of features about which I have lots of questions and very few answers. Take this spot for example:

This is on the very eastern end of the swath. We're looking at some fairly radar-dark terrain, but it's mottled in appearance, and doesn't seem to have any of the "cat scratches" or sand dunes that appear on many radar-dark areas. In fact, this picture is from a part of Xanadu that still appears quite bright to Cassini's optical remote sensing instruments, so it's not really surprising that there aren't any cat scratches. Among the dark stuff there are a few bright splotches, which, judging from some very strongly reflective bits in their interiors that are perpendicular to the radar incidence angle (radar illumination is from the top), are probably topographic features -- that is, hills. Then you can also see a few channels. Two come in from the upper left and upper right corners. One seems to connect two of the hills. Here's what doesn't make sense to me. If the bright stuff is topographically high, and the dark stuff is topographically low, I would expect channels carved by liquid to want to flow down the middle of dark areas, as far as they can get from bright areas. But there in the middle of this picture is a channel that flows pretty much straight from one "high" to another "high." Now, it's not necessarily surprising that a channel should start in one topographic high -- you expect channels to start in high places and flow to low places -- but it surprises me to see it flow from one high to another. This leads me to two possible conclusions, both of them confusing: either I am not interpreting the topography correctly, so those bright things are not necessarily higher than the dark stuff, or the things that look like channels actually aren't fluid-carved channels, they're something else, like tectonic fractures. I think the former is more likely than the latter but it's impossible to say for sure. Boy, would I love to see a topographic map of Titan.

Here's another interesting area, from the center of the swath:

With so many of the RADAR images being hard to interpret, it is nice to see one with something that's easy to interpret. It is easy to look at this image and say that we are looking at rough topography. While examining the picture closely, I also noticed what looks like a sinuous channel running down the middle of the relatively straight, slightly darker valley-like feature on the left edge of this image. That's how I expect channels to behave. (Also, if you look closely at the image, especially in the darker spots, you might see some parallel vertical striping; I'm pretty sure that's an instrument artifact.) All of those little bright linear peaky features indicate slopes facing the direction of radar illumination.

However, knowing that it's mountainous doesn't tell me why it's mountainous. I don't see a lot of evidence of parallel structures, which you might expect if the mountains were made by a tectonic process. Instead, it could be rough because somehow its elevation was increased -- pushed up from below -- and then the activity of running methane and ethane dissected the terrain. That would make it a sort of Titanian Badlands. It would jibe with what the RADAR team is saying officially about this swath; a press release from yesterday quotes deputy team leader Steve Wall as saying "there appear to be faults, deeply cut channels and valleys. Also, it appears to be the only vast area not covered by organic dirt. Xanadu has been washed clean. What is left underneath looks like very porous water ice, maybe filled with caverns." Cool.

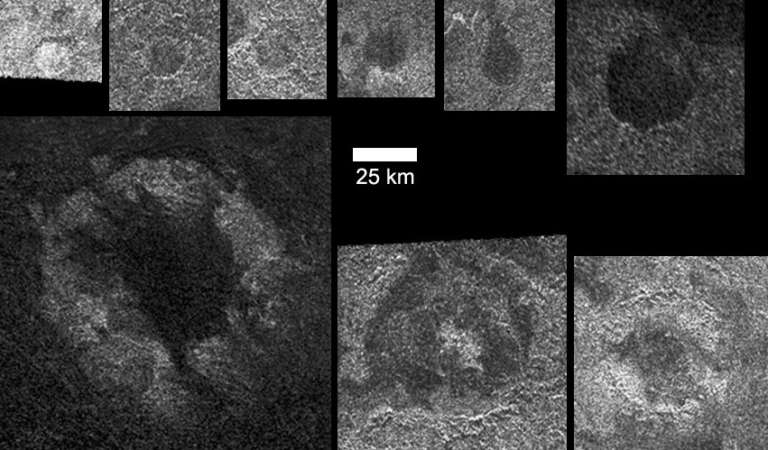

Finally, there's all of these:

I am careful to refer to these as "quasi-circular structures" rather than "craters" because, after all, some of them might be craters; some of them probably aren't; they could be volcanoes; or they could just be random patterns that sort of look like circles. Everywhere you look in this swath, you start noticing these circular features. And the harder you look, the more of them you think you see. At some point, before your brain really starts playing tricks on you, you have to call off the search. I ran in to this problem while doing research using Magellan radar data on Venus -- I was mapping large areas, looking for channels. Everywhere I looked, I saw more channels. Then I zoomed in and saw more channels. Finally I was admonished by Sasha Basilevsky for seeing things that weren't there; it was time for me to take a break from mapping.

But for the sake of argument you can say, what if at least some of these things are craters? If they are, that's a lot more small craters than have been visible on any other RADAR swath. The lack of small craters in RADAR images is a big puzzle for Titan geology. They must have formed, so the fact that we can't see them in most places means that they've either been destroyed or covered up. The fact that we can see what might be more craters on Xanadu lends support to that notion that Steve Wall was talking about, that Xanadu has been "washed clean" of sediment that covers up stuff elsewhere on Titan.

Go ahead and explore the Titan RADAR images for yourself, and see what you can find!

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth