Jason Davis & Casey Dreier • Sep 17, 2014

NASA Kicks Off a Private Space Race Between Boeing and SpaceX

Boeing and SpaceX have won multi-billion dollar contracts to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station. The big announcement came Tuesday afternoon, and marks the start of the latest phase of NASA's ambitious Commercial Crew program. The space agency aims to restore human launch capability to the United States, while reducing the cost of spacecraft development and kickstarting a new industry.

The two winning companies have spent the past several years refining concepts for their spacecraft under previous NASA contracts—the aptly-albeit-poorly-named CCDev and CCiCap, for those of you keeping score at home. Tuesday’s announcement kicked off the next phase, called CCtCap, or Commercial Crew Transportation Capability.

Boeing’s CST-100 will launch atop an Atlas V rocket, and SpaceX’s Dragon Version 2 will fly on a Falcon 9 v1.1, though each rocket has yet to be rated by NASA as safe for astronauts. Notably, both spacecraft are capsule designs, which, along with Orion, marks a complete departure away from the space plane concept epitomized by the Space Shuttle. A third contender based on this concept, Sierra Nevada’s DreamChaser, was not selected for further NASA investment.

SpaceX Dragon V2 Flight Animation Video: SpaceX

Boeing CST-100 promo video Video: Boeing

NASA’s decision to select two commercial providers was news in itself, as it was unclear if congressional funding for the program would be able to support the development of multiple crew vehicles. There was also political pressure from Congress—the most recent NASA budget passed by the House (though not by the Senate) included language that urged NASA to select only one company for continued investment.

NASA has insisted on maintaining multiple contracts to encourage competition and lower cost and risk to the agency. While these contracts are “fixed cost” (i.e. any overruns are the responsibility of the company, not NASA), failure to deliver a working vehicle with only a single contractor would, in effect, put enormous pressure on NASA to provide additional funding to ensure access to the ISS. With multiple companies, one could fail and NASA could pin its hopes on the competitor.

The work ahead for Boeing and SpaceX will not be easy. According to Commercial Crew Program Manager Kathy Lueders, there are three components to these new contracts that define a series of certification milestones that culminate in a demonstration flight to the ISS with a NASA astronaut. The first component—the milestones—look like this:

- Certification baseline review. This identifies the steps required to meet NASA’s safety and performance requirements, and outlines the timeline leading to certification.

- ISS design certification review. The design of the spacecraft and its integrated systems will be assessed for crew safety.

- Flight test readiness review. This shows that the spacecraft is ready for its demo flight to the ISS, during which a NASA astronaut will be aboard.

- Operational readiness review. The launch control center, mission control center and launch pad will be checked to ensure their final configurations match the original designs. This ensures the commercial provider is ready for regular, continuous operations.

- Certification review. This is where NASA reviews everything one last time to certify that the spacecraft and its human cargo are ready to fly.

For the second component of each company’s contract, the spacecraft will fly two to six missions to the station, delivering four crewmembers each time. This will increase the station’s standard crew complement to seven. During return trips to Earth, scientific cargo can be retrieved within two hours of landing. “This is huge for researchers in the U.S. working on time-sensitive investigations,” Lueders said.

Finally, a third part of the contract is devoted to “special studies.” NASA didn’t offer many details on this part, but did say it could be used for additional on-orbit spacecraft demonstrations.

Though the exact details on the contracts were not released—and NASA officials were extremely hesitant to discuss them—it appears that Boeing and SpaceX proposed very different prices to achieve the same set of milestones. Boeing’s proposal asked for $4.2 billion to build the CST-100, while SpaceX requested $2.6 billion for its Dragon V2. NASA would not discuss why the costs came out so differently (the space agency is currently spending $450 million per year purchasing seats aboard Russian Soyuz capsules for its astronauts).

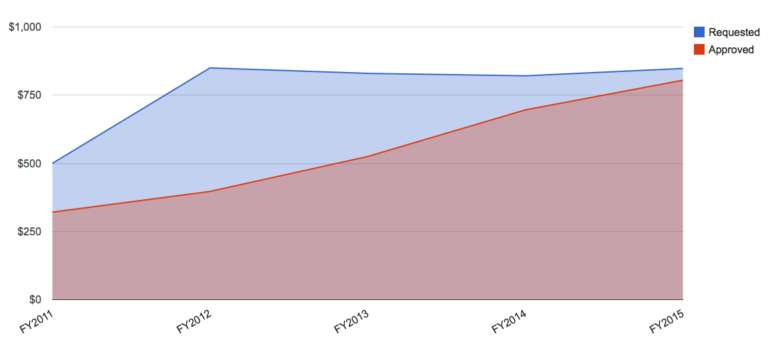

In March, NASA released its Fiscal Year 2015 budget request which projected a total of $3.4 billion for its commercial crew program over the next five years—just half of the $6.8 billion in awards announced on Tuesday. We are not yet clear on how NASA intends to pay for this larger amount, though it could be that the contracts extend beyond Fiscal Year 2019. Another possibility is that it will use other internal program funding to support the development of the crew capsules (as was the case with the commercial cargo program, which was listed on the books within ISS operations). It could also simply be that NASA intends to ask Congress and the White House for significantly more Commercial Crew funding than it had recently planned. Finally, the $6.8 billion in awards is a "maximum" amount—presumably, if the partners fly less than six missions, they earn less.

The dawn of CCtCap kickstarts a private space race between Boeing and SpaceX to see who makes it to the ISS first. On the inner hatch of the station’s Harmony node is an American flag that was carried on STS-1, the space shuttle’s first flight. In 2011, the flag was brought aboard the station during the shuttle’s final mission, STS-135. The first crew to visit the station in an American spacecraft gets the honor of “capturing” the flag and returning it back to Earth.

Pitting a nimble New Space company against an Old Space industry giant in a high-profile race to the station is an interesting strategy for NASA. For Boeing, SpaceX and their respective supporters, the playing field has been leveled. It’s easy to get caught up in the politics, funding decisions and contract details, but the wider view here is that two companies—not two countries—are competing with each other to fly human beings into space. This represents a significant shift that will have far-ranging impacts on the cost and access to space. The future of spaceflight may not look exactly how we thought it might, but it’s here, and it’s happening right before us. May the best company win.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth