Casey Dreier • Nov 25, 2013

Cosmos with Cosmos Episode 6: Travellers' Tales

Cosmos with Cosmos was a weekly series that encouraged Society members to re-watch Cosmos with a shared group, a cosmo(politan), or other drink of their choice. The Planetary Society published weekly episode discussion pieces to complement the original series before the Neil deGrasse Tyson-led 2nd season in 2014. You can currently watch the original Cosmos streaming on twitch.

Watch Cosmos Episode 6: Travellers' Tales on Hulu or iTunes.

Neanderthals didn't get around much. Beyond known settlements in Europe and eastern Russia, no signs of them have been discovered anywhere else. They seem to have lacked a certain zest for exploration and expansion.

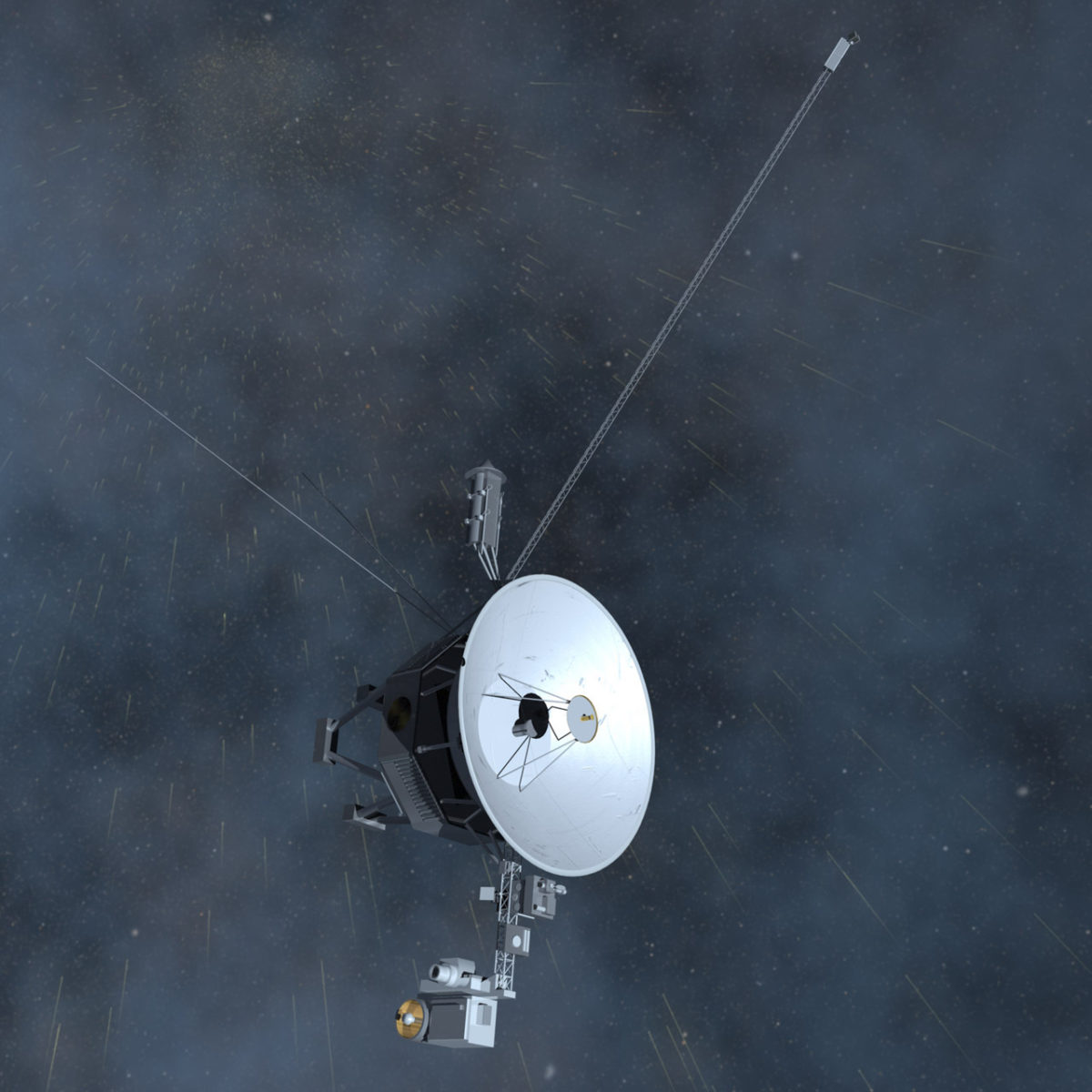

Homo sapiens, on the other hand, spread to every niche and corner on the planet. We've gone beyond that, even, exploring the Moon and creating semi-permanent habitats in Earth orbit. Where technology or cost prevents us from going deeper into space, we don't give up - we send robotic emissaries in our place. There seems to be a powerful desire in our species to push outward and explore. This strange compulsion is what has "characterized and distinguished the human species" as Sagan says early in this episode. It's what led us to create missions like the Voyagers, which venture out in the immensity, never to return.

The neanderthals had no Voyager, no sailing ships, no great feats of exploration. They died out, along with every other humanish species, victims of climate change and competition with homo sapiens. Our species went on to conquer the planet. We created the the Voyagers and the other spacecraft that explore our solar system. Why us?

Episodes 6 of Cosmos, Travellers' Tales, doesn't try to answer this question. It chooses to celebrate the that the "the passion to explore is at the heart of being human." We all need reminders of this sometimes, especially these days, when our newfound security, wealth, and comfort work to dissuade us from the expense and risk of exploration - slowly seducing us to the same fate as poor homo neanderthalensis.

Travellers' Tales is a thematic sequel to episode 5's Blues for a Red Planet, though I think it works better as an hour-long piece of entertainment. Both Voyager and Viking could trace deep roots in our culture and common history. Both exemplified the best of us, representing a purity of vision. Unlike historical sailing missions of exploration, both Viking and Voyager were untainted by greed, war, disease, and conquest. Their missions were peaceful, their goals scientific. Voyager ultimately became the more famous of the two, I would argue. It revealed far more new, tantalizing worlds, stranger vistas, and continues to operate to this day. It also traces a greater lineage than Viking, which makes for a more profound story.

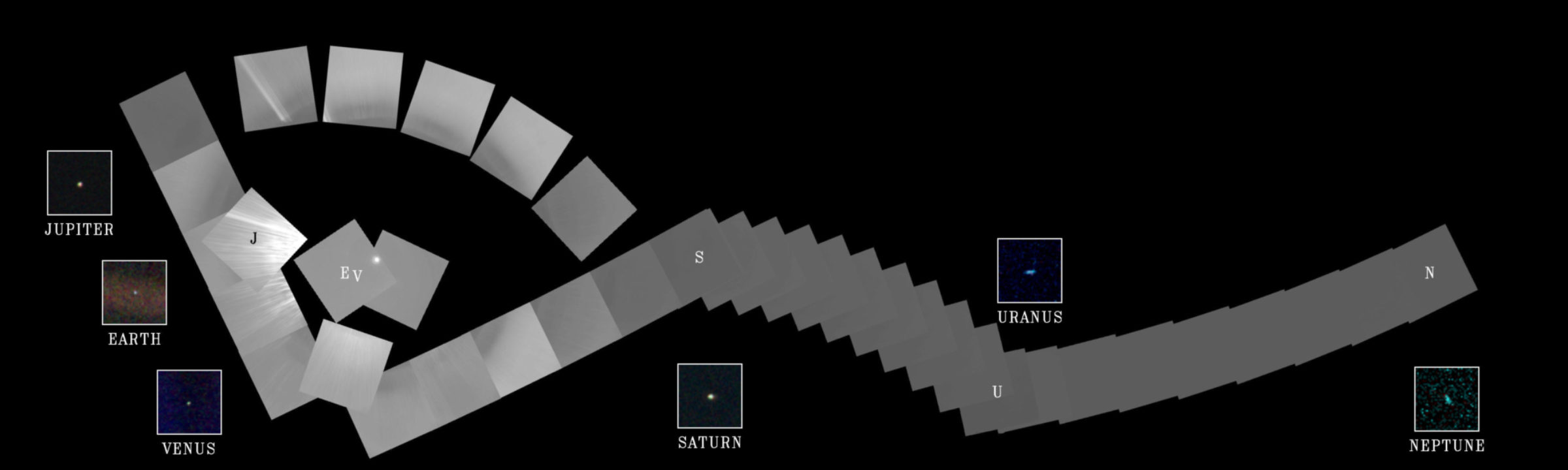

The show begins with a callback to our very first episode. We start outside and look in, traveling from the outer solar system towards the Sun, finding Earth (and ourselves) at the very end of the journey. But instead of jumping into history, Sagan takes us to the present (as it was in 1979, that is) with a look inside NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, cigarette smoke and all, when scientists were receiving data as Voyager 2 flew by Jupiter in 1979.

The parallels are drawn heavy between the Voyagers and the sailing vessels of second great age of exploration, when Europe came to dominate much of the world. Both types of ships travelled great distances over many years, both explored new lands, and both returned tales of adventure and discovery. Unlike the sailors, though, the travellers' tales returned by Voyager are always true. There are no fanciful, mis-remembered mountains lurking in the haze of Titan or shimmering creatures seen after a rum-drenched night of staring into the clouds of Jupiter. Voyager only relayed the data with a cold sobriety, leaving us to our to our wits to spin the fanciful interpretations of worlds of ice and fire and shattered crust.

After a highlighting the Dutch enlightenment and their remarkably open, adventurous society, we get a brief glimpse at the great scientist Christiaan Huygens, who discovered Saturn's rings. We see his focused efforts to peer through the newly developed telescopes of the time, struggling to understand the new worlds he saw. We are then brought back to JPL, where we see another group of scientists struggling to understand the new worlds they saw, this time through Voyager's eyes. Our tools may have improved, but our desires to understand are the same.

These two spacecraft would continue to function far beyond when Sagan (or anyone) would have predicted. Just last year, I was part of The Planetary Society's 35th anniversary event celebrating the Voyager mission with its lead scientist, Ed Stone. Not only did Voyager 2 continue on towards Uranus and Neptune, but they both have continued on towards interstellar space. Both are still radioing back information, and Voyager 1 has now passed into interstellar space. While only a few instruments still function, they still carry with them the golden record, their welcome message, our species' way of saying, "we were here."

Svante Pääbo is the Director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, where he specializes in sequencing the DNA of ancient creatures. He often asks himself the question of why humans were driven to explore and neanderthals were not.

There is a compelling argument that our drive to explore - Pääbo calls it our "madness" - is related a series of genetic mutations that are unique to humans. Variants of the gene DRD4, for example, have been linked to restlessness and risk taking, and Pääbo believes it represents the mutations that made us the type of species that looks across an endless ocean and thinks "let's see what's out there."

I don't think anyone seriously believes that our drive to explore is a work of a single gene, but I do see how a set of mutations of various genes could increase this tendency and thereby increase their likelihood for reproduction. By reaching out into new places, we exploit untapped biological niches for ourselves. We face animals that aren't evolved to hunt us. The flexible software of our brains could more quickly adapt to new surroundings, and in doing so the new surroundings would themselves select for our own adaptations that make us flexible. The drive for exploration and expansion in this sense can be considered a phenotype - the physical expression of a gene or set of genes in an organism.

But phenotypes don't just represent physical characteristics. Richard Dawkins expanded on the concept with his theory of the extended phenotype, which is any characteristic or expression in the world that helps in the survival of those genes, regardless of whether they are in the same body of the genes themselves.

Thought of in this way, the Voyagers are the ultimate extended phenotype of our species. A few mutated genes in the bodies of our ancient ancestors hundreds of thousands of years ago have found their expression in the hardened metal and golden plates of these spacecraft. Our expansionist, exploratory desires may be our most important evolutionary trait we have, maybe driving us off this planet and onto another, saving us from the vulnerable position our species finds itself in.

The neanderthals lacked this desire and they suffered dearly. Their genes didn't carry them out beyond much of anything. Our genes give us a predilection to explore, but we must consciously choose to do so. We've seen both in culture and in biology that uninquisitive, cautious groups die while the bold thrive. In which society would you rather live, one that looks out or one that looks in? As NASA budgets decrease and we find ourselves explaining away exploration as too costly, Sagan reminds us here that we owe it to ourselves to embrace the gift our genes bestowed upon us.

Science Updates

- Basically the entire final sequence of the outer planets became out-of-date as Voyager continued on past Saturn to Uranus and Neptune. We've also had the benefits of Galileo orbiting Jupiter and Cassini orbiting Saturn, with the spectacular images sent back by the Huygens probe of the surface of Titan. The moons not only rains hydrocarbons - they collect into lakes!

- Europa remains a focus of intense study, though no mission has yet been solely devoted to it. This may change in the next 10 years if NASA can fund the Europa Clipper mission to determine the characteristics of its subsurface ocean, which it sounds like they didn't know existed when this scene was filmed (how would they?).

- Cassini, which Sagan mentions, arrived at Saturn in 2004 and continues operations to this day. I can only imagine how much he would have loved the images sent back by this mission.

Stray Observations

- Much of this article and my thoughts about Voyager in general are deeply influenced by Stephen Pyne's excellent book, "Voyager: Exploration, Space, and the Third Great Age of Discovery."

It takes an important philosophical view of Voyager and its place in history – a unique approach among books about this mission.

- I love the scene of Sagan describing the technology at JPL. This being 1980, he had to explain pixels, hard drives, and other basic computing elements we take for granted. Plus, just look at the size of those hard disks! I bet they held hundreds of kilobits!

- Speaking of old tech, can you hear how loud that computer room was?

- Sagan's firm and true belief that a great society is defined by its openness to new ideas is spelled out quite plainly here with his description of 17th-century Holland. We have everything to gain by embracing exploration and digesting the new information it forces upon us.

- I do love how Cosmos shows the unbroken thread between 17th-century Dutch astronomers and modern-day robotic spacecraft. The meaning of all of this is so much greater when seen as a small part of a whole.

Quotes

- "The passion to explore is at the heart of being human. This impulse to go, to see, to know, has found expression in every culture."

- "The more you learn about other worlds, the better you understand our own. We speculate, criticize, argue, calculate, reflect, and wonder. We return again and again to the astonishing data, and slowly we begin to understand."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth