Casey Dreier • Aug 13, 2024

Why NASA does space science and not the private sector

"Space science" is process, not a commercial product

The private and commercial space industry has transformed spaceflight in the 21st century. It has lowered launch costs, reliably supplied crew and cargo to the International Space Station, sent tourists into space, and brought Earth observation and satellite communication capabilities to millions of people.

Despite these advances, space science remains primarily a public sector activity. Given constricting budgets and the growing capabilities of the private sector, it is reasonable to wonder why taxpayers continue to fund space science.

The answer lies in science being a process rather than a product and the inherent uncertainty in turning scientific inquiry into near-term profits. The private sector is not well-suited to the needs of fundamental science, which can take years and yield complex results. The public sector, responsible for the well-being of its citizens, is better aligned with the broad societal benefits and values inherent in scientific inquiry and has the resources to support ambitious projects in space exploration.

However, government agencies can and do work with the private sector, primarily as contractors or launch providers.

Enabling scientific research is a responsibility of the government

In the waning days of World War II, MIT President Vannevar Bush submitted a report to the U.S. President proposing a new paradigm for scientific research in the United States.

The report, Science: The Endless Frontier, argued that scientific progress is essential to the security and stability of modern nations, and, therefore, supporting scientific research should be a responsibility of the nation. Prior to World War II, fundamental scientific research in the U.S. was funded primarily by wealthy patrons, universities, and others in the private sector. However, the growing complexity and scale of scientific inquiry made it unfeasible to rely exclusively on that system to keep pace with new discoveries. The technological advances that secured the Allied victory, such as radar and the atomic bomb, clearly highlighted the importance of cutting-edge theoretical and applied research.

The report led to the creation of the National Science Foundation in 1950 and the addition of basic research programs in various agencies such as NASA, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Energy. The United States now spends more than $40 billion per year on basic research activities.

“Space science” is not a commercial product, but commercial companies can help

By definition, fundamental science pushes the boundaries of human knowledge and is unlikely to yield immediate results. It is not a product (one cannot package up “science” and sell it) but a social process with broad benefits, such as training a skilled workforce, developing an inquisitive and educated citizenry, and facilitating new instruments, systems, and ideas. There is also an intrinsic value to knowing how nature works, if for nothing else than the fact that humans live within the natural world that we wish to better understand.

Some scientific data can and is packaged and sold, though this is usually considered “applied” science rather than “fundamental” and is more akin to harvesting, sorting, and preparing quality data for use in explicit purposes. Weather data, various types of Earth surface observation for agriculture, and materials science are examples of applied sciences where there are markets of public and private customers eager to buy data.

Space science, however, generally does not fall into this category. While interesting, the weather patterns on Saturn will not find many buyers in a commercial marketplace, nor will understanding the early Cosmos or the potential for life beyond Earth. Nearly everything we know about the Cosmos is due to public funding that built the missions and paid the scientists to gather and study the data.

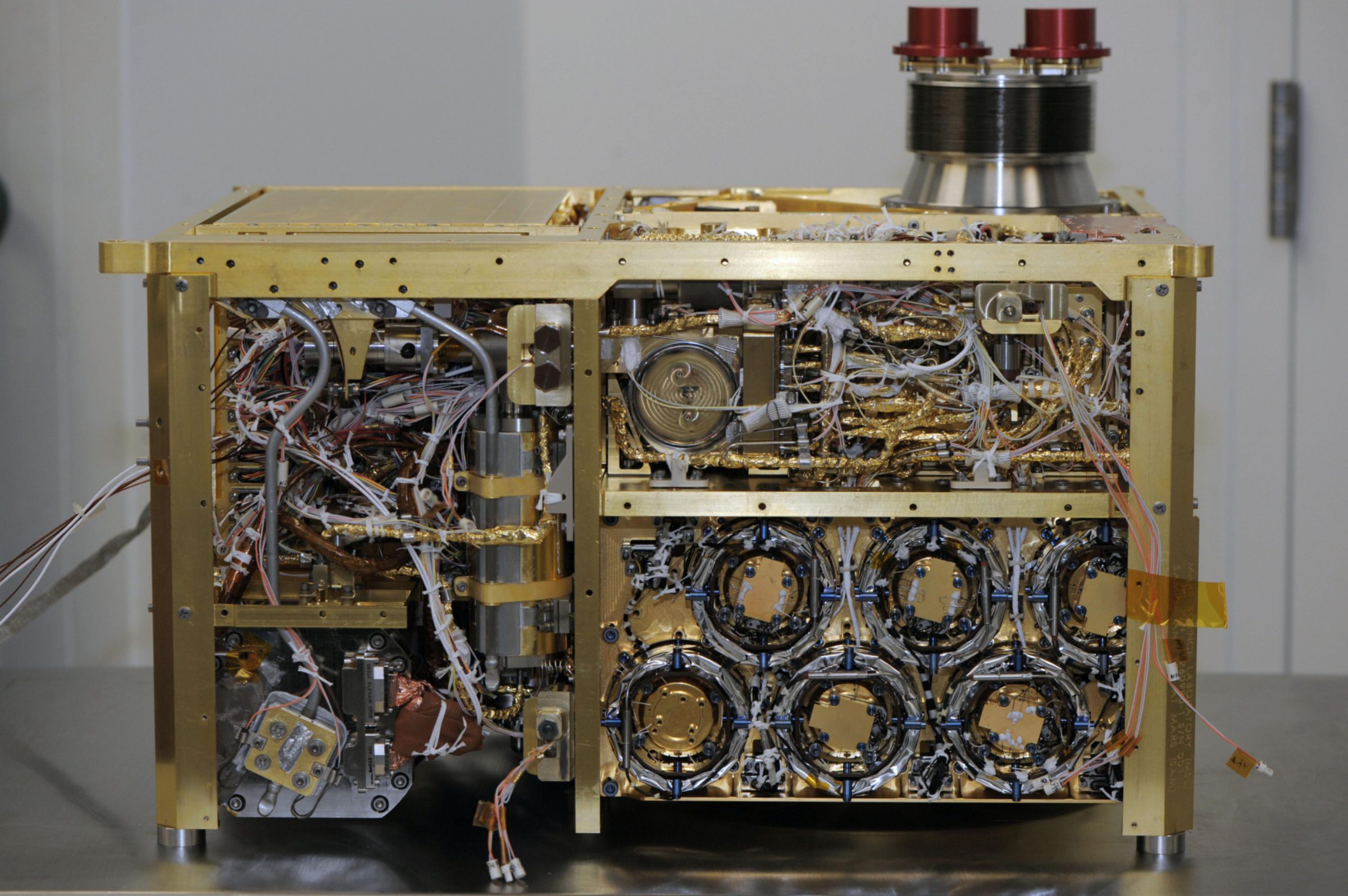

That doesn’t mean that the private sector is not involved in space science. Though NASA’s projects are ultimately initiated and funded by governments, they depend on the private sector to build components and provide other services. NASA has operated with this relationship with the private sector since its inception; nearly 85% of its annual funding is spent on contracts with private institutions and companies. NASA outlines specific needs and releases competitive contracts for companies to bid on. The agency maintains vigorous oversight over the development and implementation of these contracts and is responsible for the success of the spacecraft.

What has changed in the past two decades is that the commercial sector is now providing general services for NASA instead of specific parts. SpaceX is a space transportation company — NASA buys seats and delivery services, but the agency does not mandate how SpaceX does those things. Similarly, companies like Planet provide Earth observation services to a broad market, including NASA.

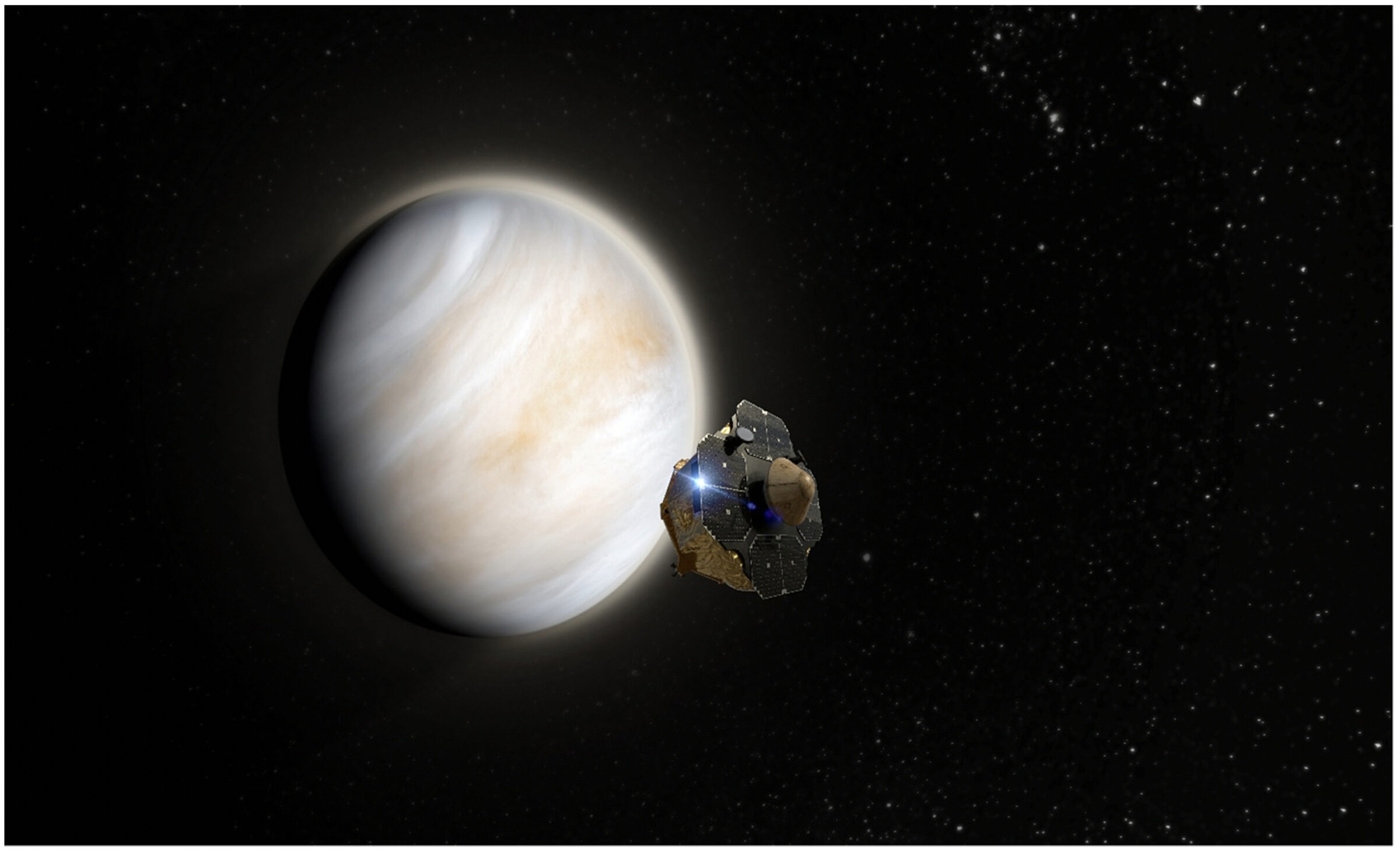

Experiments are underway that aim to bring a more services-oriented approach to scientific space exploration. NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program is attempting to stimulate commercial delivery services to the lunar surface; NASA has paid over $1 billion since 2019 to support a handful of companies in doing so. As of the publication of this piece (August 2024), there has been one partial success and one failure. The scientific instruments on these landers are paid for separately, mostly by NASA. The private launch company Rocket Lab is developing its own small Venus mission, which may launch as soon as late 2024. Peter Beck, the CEO of RocketLab, has stated that the spacecraft is a “nights-and-weekend project” and not the start of a future move by the company to sell privately collected science data. Other organizations, such as the Milo Institute, are experimenting with cooperative funding models for low-cost space science missions, though no missions have yet launched. And while wealthy individuals have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on human spaceflight missions for themselves and others, no one has yet funded an uncrewed science exploration mission.

Space science, with its hyperspecialization, one-off missions, exquisite data sensitivity, and baseline challenges of exploring new locations in our Cosmos, will continue to require ongoing public funding to maintain a broad and vigorous breadth of research. While NASA can and does leverage the capabilities of the private sector, space science will remain a domain of public investment for the foreseeable future.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth