Briley Lewis • Mar 21, 2022

Where are the moons that orbit exoplanets?

Star Wars’ Endor. Stargate’s Netu. Star Trek’s Andoria. These sci-fi worlds aren't really planets — they’re actually moons.

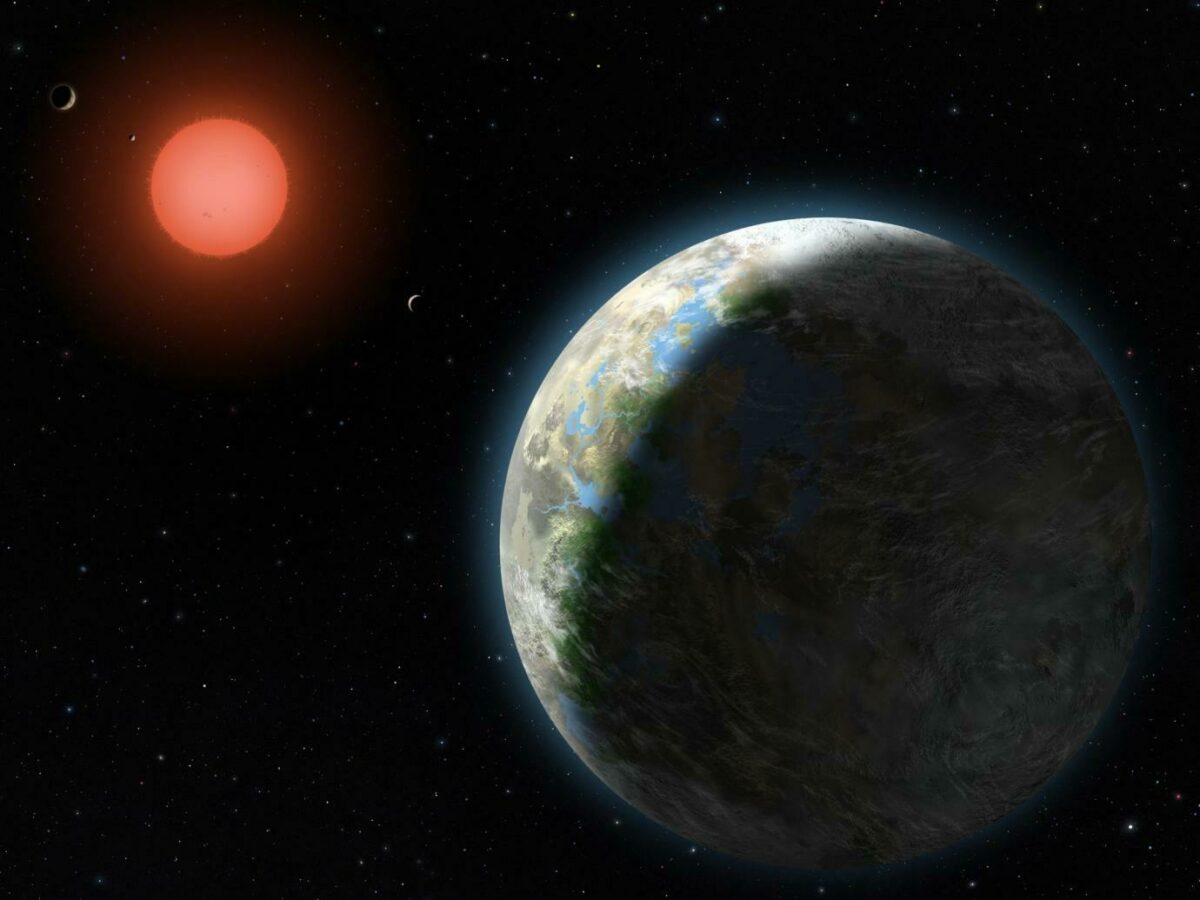

We’ve been bridging the gap between science fiction and reality for a while now, finding a multitude of planets around other stars. According to NASA, astronomers have — as of February 2022 — discovered almost 5,000 exoplanets, ranging from Earth-sized rocky bodies to giant gas behemoths more than 10 times the size of Jupiter. Spectacularly, some of these exoplanets are nothing like the planets we see in our own solar system, showing us how diverse and incredible the planets of the cosmos are.

But, what about the moons?

Astronomers are searching for exomoons, or moons orbiting exoplanets. Although this idea has been around for a while, astronomers have only recently started having success in finding these elusive worlds.

Let’s explore the motivations behind this search, how astronomers find exomoons, and what they’ve discovered so far:

The case for exomoons

We have many moons in our solar system — Earth’s Moon, Mars’s captured asteroid buddies Phobos and Deimos, and Jupiter’s horde of moons, among others. There’s no reason to expect that exoplanets wouldn’t have moons of their own.

In fact, scientists began thinking about how to find exomoons all the way back in 2007, only about a decade after the first exoplanet was discovered in the mid-1990s. Even with the current tools at our disposal, exomoons are hard to spot, but they’re well worth the search. Moons are more than just small versions of planets — they can tell us about a solar system’s past and a planet’s present.

As we’ve seen with the subsurface oceans of Europa and Enceladus in our own solar system, moons might even be really interesting places to think about and someday find alien life. Plus, with the newest and best telescopes, like TESS and the recently launched JWST, our chances of finding exomoons are getting better and better.

How to find an exomoon

There are a handful of ways to find exoplanets, most of which focus on spotting a sign of the faint planets from the bright stars they orbit around. One of these signs is a planetary transit — a small dip in the light from a star, caused by an orbiting planet that blocks some of the star’s light.

Just like most exoplanets, exomoons are too small to see directly. Still, their effects could show up in a planet’s transit — all thanks to gravity.

Everything in a planet’s orbit is a huge tug-of-war with gravity as the rope. If this game only has two players — say, the Earth and the Sun — it’s a pretty boring match. The Earth orbits around the Sun regularly and repeatedly, always hitting the same mark at the same time.

If we add in a third player, though — say, the Moon — things get more interesting; even though the Moon is a much smaller player, it has the power to nudge Earth ever so slightly, making it wobble around in its orbit a teensy bit.

With exomoons, we expect that these nudges will show up in an exoplanet’s transit as a feature known as a “transit timing variation" or TTV. TTVs are changes in exactly when the dip in a star’s light happens. They signal some difference in how the planet is orbiting — such as that tiny nudge from a moon.

This is just one way to find exomoons, though. A few other clever ideas have popped up for how to find hints of these far-away moons, such as looking for gases spewed out by volcanic moons like Jupiter’s famous Io. Other scientists have suggested it’d be easier to search for exomoons around rogue planets, which don’t orbit a star at all, taking a major player out of our complicated tug-of-war game.

The challenges of exomoon discovery

Unfortunately, images and information don't come straight off the telescope in the form scientists need to detect exomoons. They have to use well-tested techniques and other appropriate bits of knowledge to complement the data.

In order for scientists to be certain they’re seeing an exomoon, they also have to make sure they’ve been extremely careful analyzing their data. After all, we wouldn’t expect finding exomoons to be easy, especially since they’re so small and far away.

This difficulty is why, despite first suggesting in 2009 that it’s possible to find exomoons, astronomers didn’t find the first evidence for an exomoon from TTVs until 2018. Even then, the one they found — around a planet known as Kepler-1625b — was disputed and discussed by other scientists for many months. A few years later, other researchers discovered eight more possible signs of exomoons, but none really stood the tests of time and scientific debate.

What have we found?

At this point, we have a couple of strong contestants that may be true exomoons.

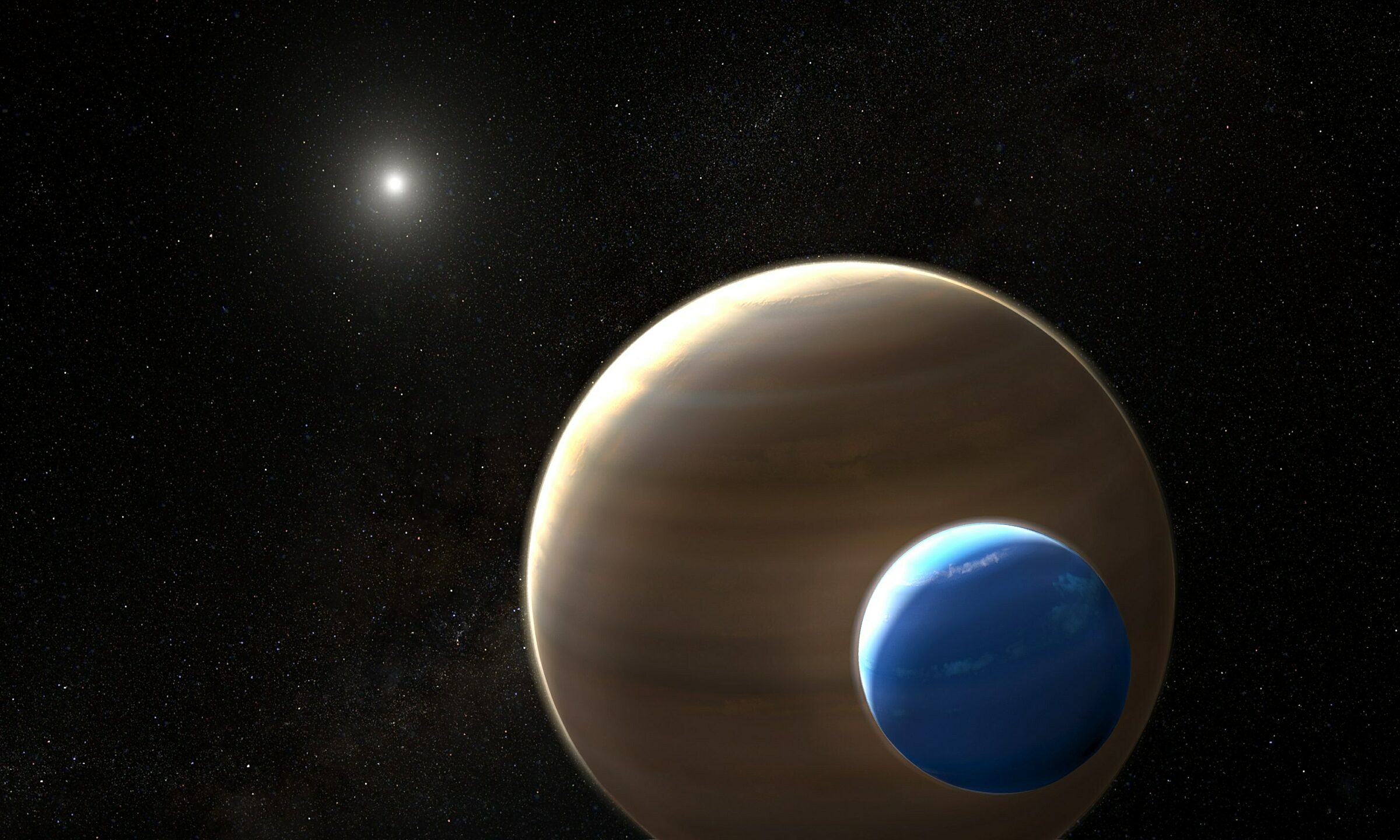

These two — Kepler-1625b-i (that is, the first moon of planet Kepler-1625b around star Kepler-1625) and the very recently discovered Kepler-1708b-i — are both huge compared to the moons in our neighborhood. They’re Neptune-sized moons around planets that are five to ten times the size of Jupiter, our solar system’s largest planet. This is nothing like the small, rocky Moon we see from Earth, and frankly, unlike any other moon in our solar system.

Just as the first discovered exoplanets took us by surprise, so too have the first exomoons, showing us there is an array of worlds far beyond the examples around our Sun and opening the door for further discovery.

It may only be a matter of time before we find a forest moon, hopefully with signs of Ewok civilization.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth