The Planetary Society • Jan 31, 2024

What went wrong with Mars Sample Return

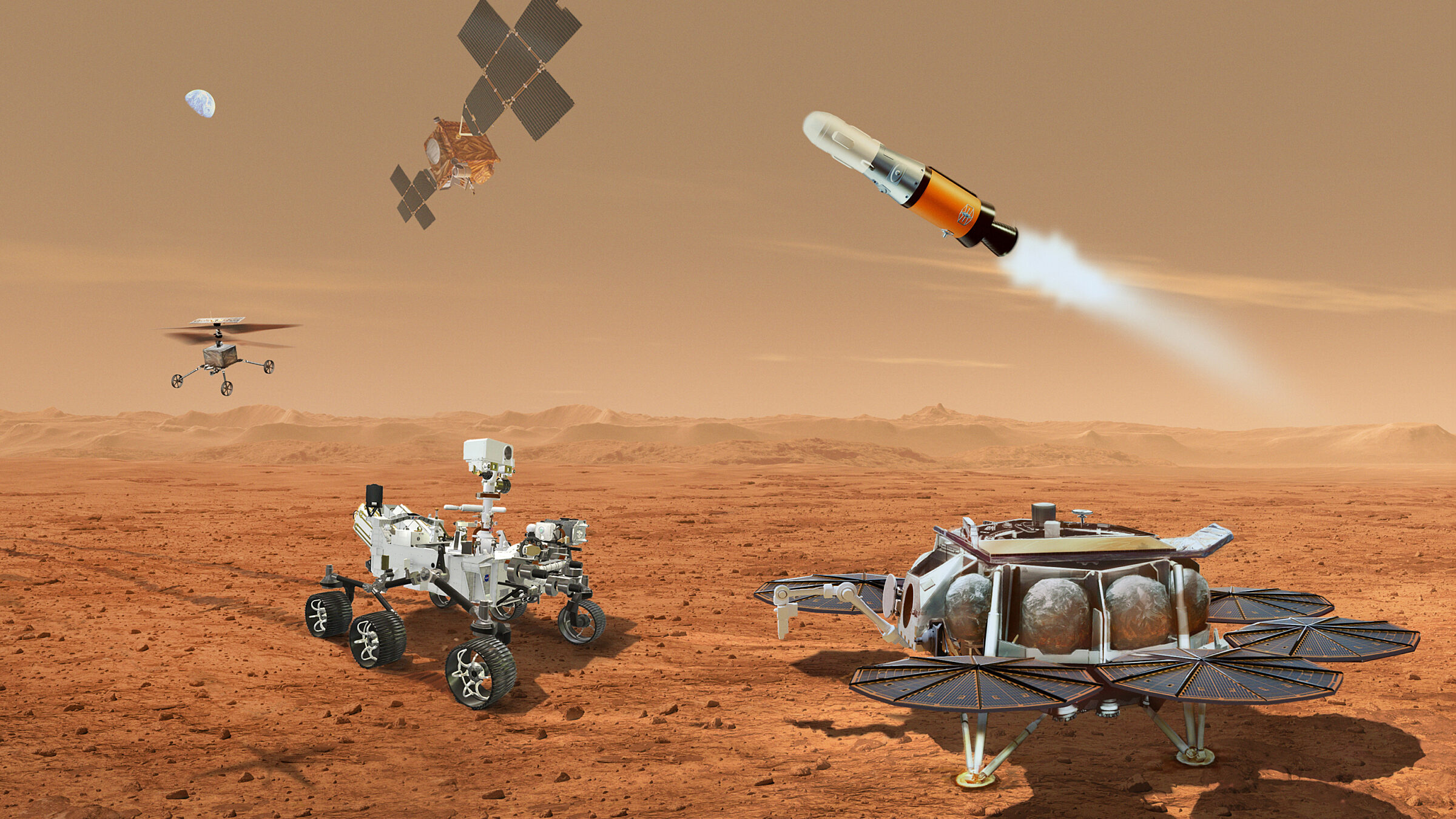

NASA’s Mars Sample Return (MSR) program was supposed to be lean, fast, and focused — no extra science instruments, no dedicated communications systems, and launching in 2026. But the effort has foundered due to its complexity and mismanagement. Originally estimated to cost approximately $5.3 billion, an independent review recently revised that total upward to $10 billion or more, and not launching until 2030 at the earliest.

In November 2023, the chair of the independent review team that evaluated MSR, Orlando Figueroa, joined Planetary Radio: Space Policy Edition to discuss the project. Their report identified management failures, unexpected design complexities, and external events such as the war in Ukraine as contributing to MSR’s difficulties. This edited transcript of the interview covers the board’s conclusions and recommendations for how NASA might be able to fix MSR’s problems and ensure a successful return of the samples already selected by the Perseverance rover.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity. You can listen to the entire conversation here.

Casey Dreier: I've read through the independent review board's report on Mars Sample Return. And before we go into the details, I'd like you to just quickly summarize the key takeaways. What did you and your committee members or board members see when you looked at this mission?

Orlando Figueroa: Number one is that the importance of the Mars Sample Return mission cannot be expressed in any stronger terms than we did. It is a very high priority for NASA, many decades in the making, and is a mission that was carefully designed to continue to dig deeper into the search for life by returning very carefully selected samples from a very special place on Mars. We have a great opportunity as a nation to advance on one of NASA’s key goals with this mission. But it is not easy. It is a very challenging and costly endeavor. To be successful in this endeavor, we need to not only invest in the best talent we can apply, but also in the resources necessary to mission success.

Casey Dreier: The review board found that there is “no credible, congruent technical, nor properly margined schedule, cost, and technical baseline that can be accomplished with the likely available funding.” The project's already spent $3 billion and was aiming for a 2028 launch window. What happened? How did NASA find itself in this position?

Orlando Figueroa: The report is emphatic in saying, “You started this effort under unrealistic expectations.” Expectations about time, when you launch the different elements, the amount of resources that would be required to do so, all of these things. And then in addition, the architecture — How do you capture the samples that are brought to orbit? How do you make sure you can know where they are if you miss the first opportunity? All of this creates an environment that is incredibly challenging.

So you're in that situation, and have an assumption that the budget on a yearly basis could go beyond what is customary even for flagship missions. And then the president's budget request didn't come close to anything that the mission required. So we said, this doesn't add up. You have too many variables, too many unknowns, too much uncertainty, and the progress to date shows that everyone is working frantically dealing with a lot of challenges. The team, to be fair, dealt with the pandemic, they dealt with the Ukraine war that changed the equation for what Europe could contribute and when, and so on.

So you keep adding to a set of unrealistic expectations from the beginning, and then have a yearly budget that cannot support it. The conclusion we arrived at was that you have to step back and revisit this to add schedule and budget resiliency under clearer guidelines because, without that, you're compromising a commitment to mission success.

Principles for Mars Sample Return

A set of principles by which The Planetary Society believes the Mars Sample Return program must be reworked.

Casey Dreier: Something that I've grappled with is that this isn't just something you can try again on. This has to work with the samples collected. You don't have the opportunity to recollect them, really. So every piece of this mission has to be reliable. Any failure on one of those points will completely fail this entire mission. And it seems like that level of mission assurance is at the core of a lot of this.

Mars Sample Return has been under consideration in some form basically since the 1970s after Viking. I recall seeing a request in the 1978 NASA budget for early study of a Mars Sample Return project.

Orlando Figueroa: Yes.

Casey Dreier: So how could any of this be a surprise to the people executing this? Why do we find ourselves in this situation given how long Mars sample return has been a goal of not just NASA but the Mars Exploration Program itself?

Orlando Figueroa: It's a great question. I think that some of the checks and balances fail to act early enough or quickly enough. Unfortunately, many circumstances just got in the way. Europe was going through their own planning, and the pandemic hit on the US side. That could have created an opportunity to step back, but it just did not happen. And I think part of it was that expectation, which was still unrealistic back then, that we were going to do it in '28. They could never get past all of these challenges — technical, pandemic and otherwise — to actually come back to a credible architecture. In the interest of trying to protect the window and getting the effort going, we started marching down a path that was not properly attended to, in my opinion.

Casey Dreier: You identify these exogenous issues, like the war in Ukraine and COVID, which threw off the timing. But at the same time, you identify several internal areas of opportunities to review mistakes, however you want to characterize them. I would put them into two buckets. One is management problems and the other one is communication problems. And it struck me that this program seemed to be designed with political optimization rather than efficiency optimization.

Orlando Figueroa: Well, I think that it should be no secret that in our country, the United States of America, for investments of this magnitude you need political support and fiscal support. So it becomes a technical challenge, a programmatic challenge, a fiscal challenge, and a political environment challenge. And let me add another piece to the equation, which is that this has geopolitical implications as well. In Europe, the member states make certain commitments, go down a certain path. And so when NASA embarked down this path, even if you set aside the political environment, there were cultural challenges that were not properly accounted for in the whole distribution of work and the organization.

Casey Dreier: The culture of the institutions contributing.

Orlando Figueroa: Of the particular institutions. So even though we can argue that politically we should have thought better, there is still the question of the cultures that were contributing to the effort, and how the way that the organization was created also created an environment that was unwieldy. And when you step back and look at all of the pieces that are contributing to what we call the Mars Sample Return mission, you can't help but to wonder how we can optimize this for success, where the cultures are aligned, where the organization is aligned, where the leadership is aligned.

By the way, this is really not quite the typical robotic nor quite the human exploration mission, it's unique.

Casey Dreier: It really fits into this mixed gray area in terms of its scope and its tight coupling. And it seems like human spaceflight programs would have more experience with this multi-center contribution model than science missions.

Orlando Figueroa: And it's reflected in one of our findings. We said you have to revisit how the agency views this and even how it reviews it in the independent review, because you can argue we were not properly armed to deal with something this unique. It's a long list of things that we hit on in the report to highlight all of the areas that, looking back, you wished someone had stepped in to do something about it much earlier.

Casey Dreier: I want to pick your brain a little bit on this concept of culture. Help me understand, what do you mean by culture? How could one NASA center possibly be so different from another NASA center? Is it really just literal culture in terms of what people share in common in terms of their backgrounds? Or are we talking about a work culture or bureaucratic culture?

Orlando Figueroa: Culture in the broadest definition is the beliefs, the norms, the motivations behind everything any one organization does. And if you were to step back and map organizations such as JPL, they are driven largely by technology. They are cauldrons of technology, they get the resources to continue to advance technology in magnificent ways. They're also, in the case of JPL, driven by planetary windows.

So you're operating under an environment where things turn very quickly and where programmatic discipline lags a little in time. It's not that they don't have it, but when you're moving so fast on technology and implementing technology and trying to match the launch window, the programmatic is usually a few months behind from where you are in the overall integration.

ESA, for example, is on the other end of a spectrum where they are more conservative because of geopolitical implications of agreements with the member states, their state of readiness, their limited budgets, what have you. They're very, very methodical. They evaluate any change. They protect their schedule.

And there are centers like Marshall, for example, whose culture is human exploration. So when you look at how they operate, how they think, and their flexibility to deal with issues, the leadership of a program like that needs to take these things into consideration because they could be a source for programmatic or technical risk if someone is not paying close attention to it. And that is a challenge to management and leadership. You cannot ignore it, especially if you're working towards a very relatively near-term window. Because we as humans then tend to drop things when we are trying to stick to a very fast schedule.

Casey Dreier: Maybe a way to think of this is that you can't just assemble these blocks mindlessly. You can’t just say “Marshall will do this and JPL will do this and Goddard will do this,” and then walk away. You actually have to spend a lot of time making sure that integration actually happens and is successful. You can't just assume it will.

Orlando Figueroa: That's correct.

Casey Dreier: So this brings me to overall management of Mars Sample Return. Going back to when this program was established, we already had the Mars Exploration Program, which you were the director of in the early part of the 2000s. That program had consisted of basically every single Mars mission since 2001, including Perseverance. But MSR, which was such a big project, was pulled out. It was not part of the existing Mars Exploration Program. It was established as its own program independent of Mars Exploration, reporting directly to the Associate Administrator of the Science Mission Directorate,. And I think this was done because that's essentially what happened to the James Webb Space Telescope project— it was pulled out of Astrophysics when it was troubled and established as its own program in order to have some level of managerial oversight. This seems, from your review board's analysis, to have been the wrong decision in that it created this uncertainty.

Orlando Figueroa: I'm certain that the decision makers were making these decisions with the best of intentions to protect the program, just like you described in comparing it to JWST, by pulling it out of the distraction of a division so that it can get the attention it deserves. Now, our argument is related but a bit different, and I want to walk through this carefully. When you look at James Webb, you know that the community at large was alarmed by the cost growth. James Webb took close to 20 years from the moment it started to the moment it was deployed. But the astrophysics community never doubted the impact of such a machine, what it meant to the community, and so the community remained completely united in this. That's not to say that they wouldn't complain or show concern over impact to other activities and so on. And as it turns out, JWST proved to be worth every penny and more in very short order.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, absolutely.

Orlando Figueroa: Mars Sample Return is of that ilk. That said, sample return was always part of the Mars Exploration Program. The Mars community as a whole must remain united behind the Mars Exploration Program and Mars Sample Return within it. Because the communities at present are pulling in all directions, trying to protect their territory, whether that’s planetary exploration, Mars exploration, or Mars Sample Return.

It is very difficult to operate in that environment when the plans were always to lay the path for Sample Return and then build from whatever is learned today, creating a continuum of Mars exploration beyond that and feeding into the agency's agenda for Moon to Mars and beyond. There aren’t the resources to allow any one of those to go in an independent direction. We need to focus the attention on the success of Mars Sample Return and lay the path for what hopefully will be a successful and continued Mars exploration program beyond that.

So from that perspective, support needs to be reflected at all levels: the government, NASA, you name it, everybody. And that has to be visible. There is no room to start pulling in different directions because people are concerned about things that they have little control over, or that at this moment in time make absolutely no difference to setting Mars Sample Return on the right path. You’ve got to look at this as a whole and see how you can best make the program successful for the sake of the agency goals and the sake of the community.

Casey Dreier: You bring up this really important distinction from JWST, which I frankly worry about as an advocate and policy analyst, because I do not see a unified community behind MSR. I also don't see a single entity taking ownership of it, the way that you had with JWST.

And all that science return is deferred until these samples come back. So I worry that without the scientific buy-in willing to stand behind this, plowing forward with a billion-plus-dollars-a-year program is going to be really difficult.

Orlando Figueroa: Yes. And that unifying force and leadership must come from NASA. This cannot be relegated to any center, JPL or otherwise, to be the only voice speaking for the importance of sample return to NASA, to the nation, to the future of Mars exploration, and to the Moon to Mars initiative. It has to be a respected and powerful message. It is so critically important to unify the community because that community on its own is just going to tear itself apart if they lose focus on the importance of this mission.

Casey Dreier: You identify in the report that NASA has not been sending a consistent unified message and the strategic and scientific values have not been communicated appropriately. You even highlight that MSR management doesn't even have access to NASA's very top leadership, which again strikes me as extraordinary. How did we get to this point where MSR was being almost functionally ignored?

Orlando Figueroa: I wouldn't jump as far as to say that it was ignored, but I can say that it definitely was not getting the attention it deserved and the communication of the importance to the nation that it deserved. To be fair, the agency has Artemis and other big things that are of concern, but missions of MSR’s nature need that kind of attention and community support that JWST got — people rallying behind the best talent, a Nobel Prize-winning principal investigator, and the mission’s importance being repeated, communicated, amplified, reflected in images, in how everyone spoke about it. That wasn't the case here. In our view, the agency wasn't quite connecting all those dots and sending a powerful message that MSR was important to us as an agency, us as a nation.

Casey Dreier: It seems like Artemis may be the explanation for that, since Artemis ticks off a lot of these similar arguments — it’s an international cooperation, it’s a multicenter broad effort, it's brand new, it's under development now, but it's also an order of magnitude larger in expenditures and scope. Does that just suck up all the oxygen from the leadership in terms of their attention?

Orlando Figueroa: In my opinion, there is no reason why they couldn't do both. There is a human exploration side of the House and the science side of the House, and they both have a special role in what they contribute to NASA and the nation. It's just that the message needs to be communicated, repeated, underscored constantly.

Casey Dreier: I just want to go back to the scientific community division here and how they're thinking about Mars Sample Return. They look at the fiscal year '24 NASA budget, which literally states, “We're not going to do your priority mission in Heliophysics. We're not going to do your priority mission in Astrophysics because of Mars Sample Return.” So NASA itself, via its budget requests, seems to be explicitly dividing the scientific community in this zero-sum game, and almost casting blame on MSR. And this was before your independent review panel upped the total budget expectation, almost doubling it.

Orlando Figueroa: Well, to be fair, there are flagship missions and then there are flagships, right? There are missions in the $2 billion to $5 billion category like the Roman Space Telescope, Europa Clipper, and past missions like the Hubble Space Telescope, Perseverance, and Curiosity. Incredibly difficult missions. But then there are missions that programmatically and technically are at the upper end, like JWST and MSR. Missions of a magnitude and complexity we’ve never dealt with. So this is one of the reasons why we also highlighted that this is unprecedented for how you do business. The yearly budget being requested for MSR is more than JWST ever requested in any given year. But that’s because JWST had an escape path, which was to move the schedule.

Casey Dreier: It wasn't tied to an alignment of a planet. You could launch it pretty much whenever you wanted to.

Orlando Figueroa: You could go whenever you wanted to, and with MSR it is a different equation. And thus why we also say you have to look at robustness and resiliency, taking into consideration that at any given year a hiccup,whether it is fiscal or technical or something else, may put you in a situation where all of a sudden it makes it even more difficult for the agency to deal with.

Casey Dreier: Was there ever a discussion about bringing the Mars community into this mission more at this stage? Should we add some scientific instruments, some so that no matter what happens if something goes wrong with the launch, we have instruments on the sample return lander or the fetch helicopter that we could still get some science out of? Was that part of this discussion and is that something NASA should consider going forward?

Orlando Figueroa: No, we did not look at adding any other instrumentation or science. There are project scientists supporting the effort and there is a program scientist at NASA headquarters, but not a fully unified voice that says this is what we are all about in Mars Sample Return.

Casey Dreier: Did you consider the role of commercial or private contributions to a reformulation of this project? And if not, why isn't that appropriate in Mars Sample Return?

Orlando Figueroa: There are two things that are alluded to in the report. One is that there are many large contracts already in place with the commercial sector.

Casey Dreier: We're talking about classic aerospace contractors though, correct?

Orlando Figueroa: Correct.

Casey Dreier: But not necessarily what one might consider commercial is these days — companies putting their own skin in the game. This is more like standard contracting methods.

Orlando Figueroa: That is correct. If you look at who is participating, government or otherwise, there are people that have a lot of experience doing this kind of thing. They have done this before, they know the risk, they know how to manage it, et cetera. If you look at the architecture alternatives, you could consider whether there is a point of entry for others to participate, but you need to be careful that they have the experience and expertise to do what you may think about asking them to do because this is very hard. If a goal is to bring some commercial providers along, you need to prepare yourselves for the risk and uncertainties associated with it.

Casey Dreier: Just to build on what you're saying, new commercial space ventures need lots of shots on goal. You need lots of opportunities to try and practice. And this is a bespoke one-off mission, This is it. And as we discussed earlier, it has to work. It's like at this level, you're paying for that assurance that this is going to work.

Orlando Figueroa: Absolutely. And what you see happening with commercial involvement in the Artemis program right now is that they're going to get to practice and, knock on wood, we will get there. So you can imagine that being extended to the Mars environment. But we're not quite there yet and they are two different beasts. So it has to be part of a longer-term agenda that says we're going to also start bringing along a community. And by the way, the Mars Exploration Program had these things as their goals for the future — to bring the commercial sector along to provide communication infrastructure, for example.

Casey Dreier: Did your review board ever just consider saying that MSR isn't worth it? That the opportunity cost is just too high?

Orlando Figueroa: That's a great question. The board you may have noticed was very diverse. I mentioned you had technology, commercial sector, private sector, system engineers, managers, political backgrounds, you name it. We ended up with an incredibly competent and diverse board. One of the things that I asked them to do, because I was sensing these tensions within the community, was to do the homework so that we as members could convince ourselves as to the importance and challenge of this mission. And the National Academies of Sciences brought along a lot of material that rebuilt the history of why this is so important. Because we felt that if you're going to invest any sums of money in the territory, even about $5 billion, we’d have to be convinced that this was worth doing. It was not that this isn't worth doing. It is that this is not worth doing if you're not going to do it right. If you're not going to be committed to this all in, that is a formula for potential disasters.

Casey Dreier: Don't half-ass your way to Mars Sample Return. Kennedy challenged Congress basically with that formulation of Apollo — either we do this all the way or we don't try.

Orlando Figueroa: And the comparison is somewhat uneven, but it is that kind of conversation. We know what it takes, we know that this is going to be an end-to-end effort. And we know that the story doesn't end with samples landing. A new stage begins with the samples landing just like OSIRIS-REx and the Bennu samples. And even with the Apollo Moon samples, where now with new instrumentation and technology we are uncovering things that were not possible 10, 20 years ago. So that whole story is going to evolve and I have every expectation that we're going to be blown away by what we learn as a world community. But as you said it, you are all in or you're not.

Casey Dreier: We've seen people in the community say that if we don't do Mars Sample Return, then some other mission can be done instead. Mars Sample Return right now in the last budget approved by Congress received around $850 million. That's larger than the entire Heliophysics division. But if this project were canceled, you don't anticipate that this money would flow back into planetary science or even the science mission directorate.

Orlando Figueroa: Yes. I mean, anyone that has taken the time to familiarize themselves with the fiscal environment and how NASA and the government works will know that things don't work that way. It's not rob Peter to pay Paul. And so those that are assuming that just take it out of Sample Return and distribute it equally among your children, it just doesn't work that way.

Casey Dreier: And I think that's really important to remember that sometimes doing big things can actually help coerce bigger budgets. Because you're ambitious and pushing for something new, which gets funded not from a preexisting pot of money but by NASA deciding what it wants to do and then trying to get the money to do it.

Orlando Figueroa: Yes, and that is why it is worrisome to see a community divided. And the present fiscal environment just doesn't help because it amplifies the fears of the community. But I once again emphasize that this is where agency leadership needs to step in and be consistent and unified in a message. This is what this is all about, why it's so important to us as a nation, to ESA, our partner, for now and for the future — we are either in or we are not.

Casey Dreier: Can NASA do this?

Orlando Figueroa: My view is that they need to take every one of the recommendations darn seriously, number one. Number two, do I have confidence in NASA being able to pull off big things like this? Absolutely. I lived it. I know what it means. We've been in situations like this before. But this is where actually the leadership needs to be visible, step in, continue repeating the message over and over and over. The moment they relax in that responsibility, we start falling back behind.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth