The Planetary Society • May 04, 2023

What happened with Psyche?

A first-hand account from JPL Director Laurie Leshin

In 2022, a mission being led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) missed its launch date. Psyche, a mission to an asteroid of the same name, was delayed by a year and ran over budget, causing a ripple effect of delays and budget woes for other JPL-led missions, notably the VERITAS mission to Venus which was delayed indefinitely. According to an independent review panel, workforce and management problems at JPL were at the root of Psyche’s missed launch date.

Dr. Laurie Leshin took over as JPL director shortly after these problems were discovered. On Jan. 6, 2023, she joined an episode of Planetary Radio: Space Policy Edition to talk with The Planetary Society’s chief of space policy, Casey Dreier, about what happened with Psyche, what exactly the problems were — ranging from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to outdated human resources policies and competition from private space companies — and what JPL is doing to make sure it can hire, retain, and effectively use the best minds in the space industry.

The original transcript has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Casey Dreier: Dr. Leshin, thank you for joining me today on Space Policy Edition.

Laurie Leshin: It's great to be with you, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Great having you back. I’d like to dive right into the big topics on this episode: the Psyche Independent Review Board, the mission to the metallic asteroid that was delayed this year, and the larger management challenges facing the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. First, I want to make it clear that you came in just as this was happening.

Laurie Leshin: Yes, three weeks after I got here I figured out we weren't going to make the launch.

Casey Dreier: The Independent Review Board’s (IRB’s) report about what happened with Psyche included issues with workforce. Is there a workforce problem not just at JPL but in aerospace in general?

Laurie Leshin: Yes. Every single org we have talked to since the Psyche Independent Review Report came out has said that looking at the slides they could scratch out “JPL” and put “X aerospace company,” or “X NASA center.”

This manifested in such a way that it's making visible to everyone the challenges that we're facing across the aerospace sector. There’s fantastic growth of the commercial space sector, the founding of the Space Force and growth in military and intelligence community space work, growth in civilian space work, growth in international space work. There's no doubt that there's a huge amount of opportunity out there. And this means that employees in the aerospace sector can be really picky and really think about where they want to go and what they want to do. Frankly, I think that's going to make us all better. It's going to make us need to be better employers. It's going to make us need to have a better employee value proposition.

Casey Dreier: I actually wanted to touch on that very issue. That was one of the key items called out in the report was retention and successful hiring of talented and promising individuals. This strikes me as something of an irony, that for so long NASA has been trying to build a commercial space sector and to make it more vigorous and expansive, but it seems now that there may be some hemorrhaging of talent; the people that NASA paid to train, invested in, and depends on are now being lured into the private sector. It's not necessarily a bad thing, but it certainly changes the game for you, I imagine.

Laurie Leshin: It does change the game, but in the best possible way. Look, the last time I was at NASA in the 2010-2011 timeframe was when we were starting to really work to support the commercial space sector's emergence, and guess what? We were wildly successful. So now there's not only government money in that, but a ton of private money. It means that there are really interesting emerging places to work for people with backgrounds in aerospace. This is, I think, the best possible problem to have.

Frankly, it's not a bad thing if more people in our business get more different experiences, that there isn’t only one or two places to work. We've got to work on making sure this is a great place to work, that we've got exciting and challenging and inspiring missions for folks at JPL to work on. That way when someone leaves for a few years, maybe they'll come back with a different set of experiences that can help us be better.

Casey Dreier: What do you think JPL's argument is? Why come to work for JPL? How do you pitch yourself as a great place to come and work, or what are you doing to change?

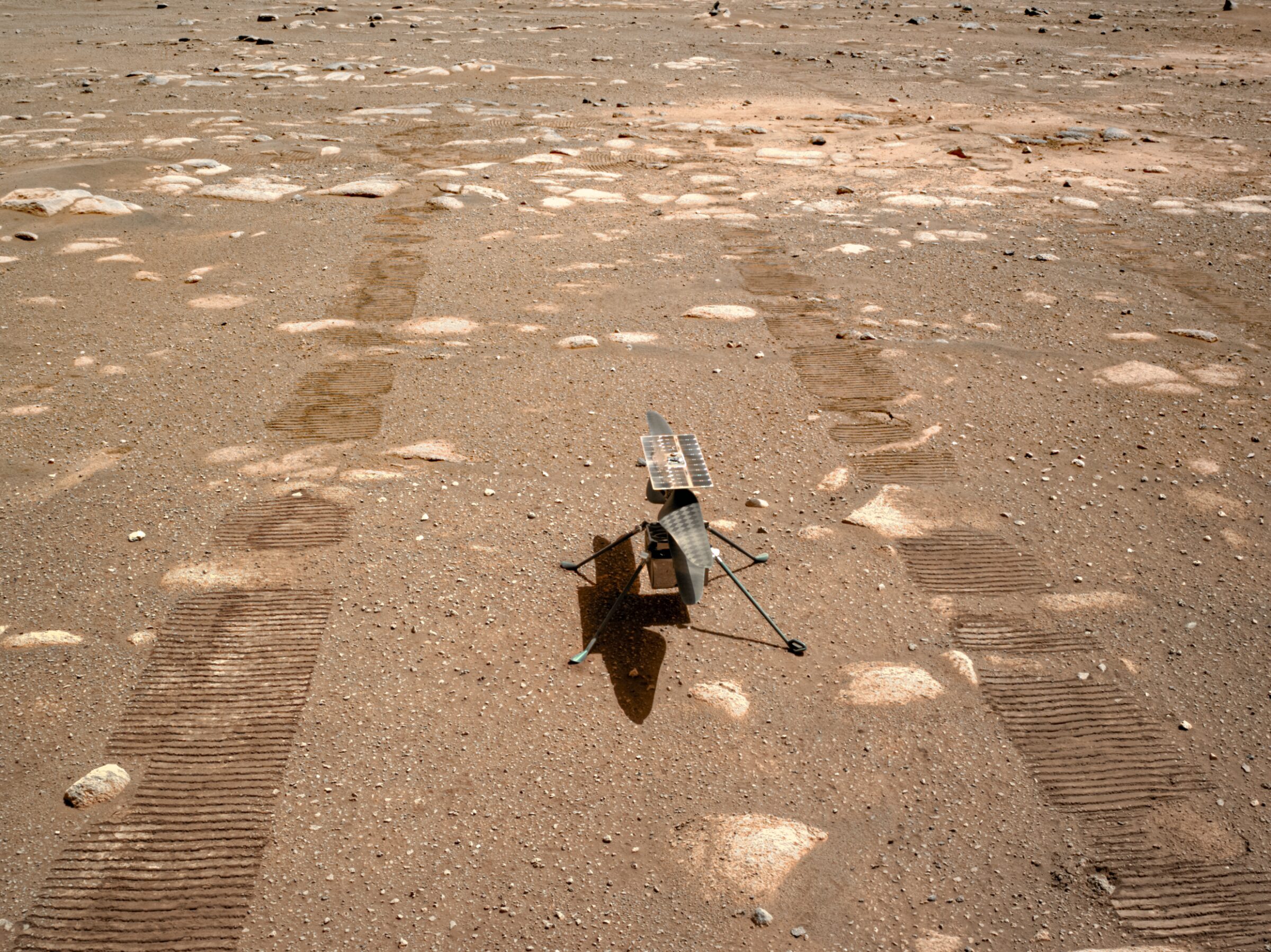

Laurie Leshin: So this is about our mission and our missions. We are fundamentally a research and development organization that's working to answer the most profound scientific questions that you can ask. Things like, "Are we alone in the universe?" Things like, "How are we going to adapt to and prevent more climate change?" These are really challenging things and we do it at JPL with a specific approach that says, "We don't want to build the tenth something or even the fifth something. We want to build the first of a kind. We want to build something that's one of a kind. We want to build something that really drives the frontiers of capabilities for robotic missions," and that is really inspiring to a lot of folks. We want to fly helicopters on Mars. We want to do that thing that no one's ever done before. For a lot of folks, that's going to be really exciting, and we want to do it in a way that frankly, offers people some flexibility, that really respects families, that embraces everyone as who they are. We want to do it with an environment that is truly diverse and inclusive and we're working on that to make it better. We clearly have great things to work on and we're working every single day to continue to make this a great place to work.

Casey Dreier: Are there things you can talk about already in terms of what's changed in terms of how you're approaching workforce after this, and just in general from what you are bringing to the role?

Laurie Leshin: Well, we've been focused in a few areas. One thing that we announced very recently is, believe it or not, we did not have paid parental leave at JPL. We've just announced eight weeks of paid parental leave for both parents, and this for after birth, after adoption, or after a new foster child comes into the home. This is basic stuff and I was really pleased that we were able to work with our colleagues at Caltech to get that done. It's amazing how much of a difference things like that really make to folks, so I'm glad we were able to do that. We're also getting ready to roll out our diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility strategy and it's a very JPL kind of strategy because it's really focused on trying to invent the science of all this, to really do experiments so that we can measure how well they work.

Casey Dreier: Well, it strikes me, again, how things that are at first a crisis can actually be this tipping point into action. But at the same time, what has Psyche revealed for JPL management? Because one critique was that there wasn't enough penetration into the project, that problems didn't get reported up. How are you using this information to improve management for other missions? Mars Sample Return, for example, is spending more per year than NASA's entire Heliophysics Division right now. So a delay there because of management issues could be catastrophic to some degree. How has what you’ve learned from Psyche been informing these other areas that are even larger and more complex?

Laurie Leshin: We're working our way through what we heard from the IRB, and we've got a response team that's being led by one of our most senior leaders. They're turning these things around and looking at them from all angles and thinking about how to address them. The Psyche team has already addressed everything in the report. They were doing it in real time and that's one reason why the mission got continued and will launch next October.

One of the big challenges that we’ve addressed is remote work. There was literally no other mission whose development happened during the pandemic as much as Psyche’s did. The mission was confirmed six months before the pandemic started.

So that was a huge challenge for a team, especially a distributed team who was flying around a lot to be together. Even those who were in the same city, they couldn't all be in the same place. It's quite clear that the way that we had implemented Return to Lab at JPL, which happened in early May 2022 right before I started, actually was okay. But it was like doing remote and hybrid work in the worst possible way because people would come to the lab and then would sit on WebEx all day because their teammates weren't here.

Building something that's one of a kind and first of its kind with large teams diverse in terms of background and expertise is really tough to do when you're not together pretty much at all. The work we do is most effectively done in the lab — not every day, not every task, but there has to be more of that togetherness.

So we went through and tried to simplify it and make it more consistent. We said to the projects, "We think you should be setting out certain days of the week that people are here." We gave people time for this adjustment because I'm not going all Elon here, "Everybody get in here by Monday." We're not doing that. People need time to get their lives together, but we’ve got to get not just the work done but the job done. We need the teams together more to really do that.

We also do have some people on our team who live elsewhere and work fully remotely. Some teams and some jobs lend themselves to that. But we still need to get the full team together at least quarterly to make sure that people are getting the facetime they need, and to make sure that young people are really building those relationships with more senior mentors.

Casey Dreier: Is it fair to characterize Psyche as an unintended experiment of building a spacecraft in a hybrid remote working environment?

Laurie Leshin: Yes. Let's never do that again.

Casey Dreier: It's actually amazing how close it came to launching, all things considered.

Laurie Leshin: Well, I actually think that's right, Casey. Look, it's not great that we shipped a spacecraft to Cape Canaveral and then later decided it wasn't ready for launch. I get why that's not great, but the truth is that they overcame almost every obstacle against incredible odds. I think we should be honestly celebrating this team for not launching when they shouldn't have. They raised their hand and said, "We're not ready and we shouldn't do this. It's too big a risk," and it's really hard to do that.

The other thing I was really impressed with the IRB for is that it identified the importance of what they called the ‘informal safety net.’ This is the fact that when you're doing things that are incredibly hard, stuff always happens. Every single day in this lab, people are walking down the hall to their neighbors saying, "I can't figure this thing out," or, "Something doesn't feel right here. What are your thoughts about this?" Or doing it in the cafeteria at the coffee cart. The senior people who know everything lend their expertise informally across every project at this lab and that was obliterated in COVID. We all know that we missed those hallway conversations. What we didn't realize is how essential they are to being able to launch a spacecraft on time. So that, again, really suggests that more time together in the lab — it doesn't have to be every person every day — but more time together is really essential.

Casey Dreier: Does it help that other tech companies are also reaching the same conclusion? It seems like a lot of companies are really pushing people to come back.

Laurie Leshin: Yeah. Lots are, including the Googles and the Apples, actually. We're hearing they're going back to three days a week and many in the aerospace business are doing the same. When you're trying to do hard stuff, none of us can do it alone. We've got to do it together.

Casey Dreier: One of the questions I have, particularly in relation to Psyche, is, how do you know what is real or systemic in terms of the problems you're trying to deal with? How much of it was just this bizarre, hopefully once-in-our-lifetimes consequence of a global respiratory virus that's swept through the world in three years? How do you try to choose? Because I could see overreacting potentially, assuming something is systemic where it's really just a bizarre reaction or consequence of COVID?

Laurie Leshin: So you're asking the $64 million question. This is exactly the conversations we're having internally all the time right now. The truth is that the management within the project didn't realize what was happening, so there's no way that at the director level they would've realized it. So the worry is we're going to put in a whole bunch more bureaucracy to deal with management oversight, when in fact, what we need to do is figure out, "How do we just make sure that the people who are on the front lines with the issues are raising them up appropriately internally?"

Yes, I already am doing more in terms of interacting with the projects, just having heard the initial feedback from the IRB. But we've got to really get to the root of the challenge and figure out how much of it is COVID related. We're trying to make that balance and not overcorrect, but I think for that reason, it's not going to be a one-off set of responses. We're going to try some things. I'm a big believer in testing as you go and learning along the way and adjusting, not waiting until you have the perfect answer, but actually implementing some things and then assessing how we're doing and keeping the questions going. I think that's going to be really essential here.

Casey Dreier: What would you characterize as the most important near-term or immediate challenge that JPL is facing?

Laurie Leshin: For us, we really do need to keep focused on the work ahead of us. The next year, year-and-a-half of work, we're going to be very busy and we need to stay focused on making sure that work is done and done well, not taking our eye off the ball. So it's fairly tactical I would say. I think if we do well in the near term, the long term will take care of itself. Not that you don’t have to pay attention to the long term. Of course, we pay attention to it.

Casey Dreier: Is it fair to say that the most important general long-term policy that benefits not just JPL, but workforce issues with all of NASA is having a clear, inspiring mission that's boundary pushing at the core?

Laurie Leshin: It is. If the rule for a new mission is, "No new technology, don't do anything new," I worry that in the long term that sets us up to drive away our most capable folks. They will go somewhere else and find it in the private sector if they can't find it through NASA funding. So we work very hard to invest in new technology.

Mars Helicopter is a great example. Mars Pathfinder, too. We would not have Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, or Perseverance if it weren’t for that cute little rover that started as a tech demo. That is what we do best at JPL; we think of those slightly crazy things and we figure out how to try them and then it ends up driving the whole program. So if there's one thing I could wish for in the future, it's that we would be able to continue to do that, to continue to drive those frontiers. That's how you attract a great workforce and that's how you build a great place to work.

Casey Dreier: There's an interesting tension there that in order to have total cost assurance that you'll never have something like another Psyche or another cost overrun you want predictability, familiarity, all of the things that were just the opposite of inspiring. So in a sense, you have to lean into the risk in a smart way in order to really provide what you're talking about. That's what brings out the best in the workforce. I think that's an important thing for policymakers to remember or to really embrace, that if you want the government-funded stuff to stay at the forefront of this, failure's going to have to be by definition part of this.

Laurie Leshin: Failure, and not having exact cost predictability at the very beginning of a new project. We're in this place right now with Mars Sample Return. Again, it's the most complex planetary mission ever attempted, and we really want to do it well. We want to make sure we've thought it through. So we're working on those things right now. We're pushing really hard to have the team try and do that in a cost-constrained way. It's a huge challenge, but a really exciting one, actually. I couldn't ask for a better challenge.

Listen to the full interview on Planetary Radio: Space Policy Edition.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth