Jason Davis • Jul 24, 2013

Interpreters: the ties that bind international spaceflight

When Luca Parmitano's helmet began filling up with water last week during a NASA-led spacewalk, ground controllers at Houston's Mission Control Center scrambled to find the cause. After the situation worsened, Parmitano and Chris Cassidy were told to terminate the spacewalk and head back to the airlock for repressurization.

On the other side of the globe—6,000 miles away and 9 hours ahead on the world clock—the staff inside Russia's Mission Control Center were alarmed at what they were hearing. The real-time English chatter was too fast to follow, so their ears were trained on a single person: the interpreter.

"The Russians were listening to our interpretation and asking questions," said Elena Kozhukhov, a senior Mission Control Interpreter for TechTrans International, which provides interpretation services for the International Space Station. At one point, Parmitano stopped responding, unable to hear transmissions as the water pooled around his ears. Kozhukhov recalls the Russians anxiously asking, "What's the status? Is he okay?"

Soaked but safe, Parmitano made it back inside the station. His Russian crewmates, along with NASA astronaut Karen Nyberg, were waiting at the airlock to assist.

"It was really scary to know that there is a person that needs help but there is nothing you can do," Kozhukhov said.

Fortunately, situations like this are far and few between. In spaceflight, communication can be an astronaut’s best tool to remedy a dangerous situation. When that involves crossing language barriers, the role of the interpreter is vital, yet often overlooked.

Elena Kozhukhov moved to the United States with her parents in 1989. She grew up in Moscow, and was just 14 when her father moved her family to America to pursue business opportunities in Seattle, shortly after President Mikhail Gorbachev opened the border for Soviets wishing to leave.

At the time, Kozhukhov didn’t want to go. All of her friends and family were still in Moscow, and she had only a rudimentary grasp of English. Upon arriving in Seattle, her father opened a translation and interpretation services company, but business was scarce. That would change, however, after he caught wind of an interesting opportunity in Houston: providing translation and interpretation support for the proposed Shuttle-Mir program.

"NASA was entertaining the idea first of whether it would be possible or not to do the joint program like they did with Apollo-Soyuz," Kozhukhov recalls. "First they wanted to see if it would be possible to put the docking mechanism on the shuttle."

It was highly specialized work. NASA needed translators and interpreters that also had engineering and technical backgrounds. Her father was a natural fit, having graduated from Russia's Radio Technical Institute. He began traveling to Houston for work, contracting interpreters from his business to TechTrans International, a company founded specifically to fulfill NASA's translation and interpretation needs for their growing partnership with Russia. In 1993, he moved to Houston for good. Elena was attending the University of Washington at the time, but her father wanted her to join him.

"My Dad said, 'We really need you here to help us build the business,' so I moved in 1994," she recalled. "We were so busy with the program, and it was just so interesting and so new. Sometimes we were working nonstop for days, sometimes for 24 hours."

Kozhukhov said the work was difficult because she first needed to learn NASA's acronym-laden technical jargon.

"It was not even so much English as just a totally different language of its own," she said. "I had to learn pretty much everything from scratch. I could translate the connecting words, but basically, for the first three months, I sat and listened to my father interpret."

Despite its challenges, she found the work exciting. Because of the time difference with Moscow, she would often arrive at work for teleconferences at 5:00 a.m.

"It was like putting puzzles together. I was looking forward to going to work every single day."

As Shuttle-Mir got underway, Kozhukhov and her father began working inside Houston's Mission Control Center. Her first mission was STS-63, the so-called ‘near-Mir’ flight in which Space Shuttle Discovery rendezvoused with the orbiting Russian complex. When the shuttle began docking with Mir during later missions, Kozhukhov knew her role was important.

"You have a shuttle that has to do certain functions, and you have the Russians that can also control the station," she said. "So in order for the Russians to not inadvertently turn on the thrusters, they would have to disable them."

After Shuttle-Mir, Kozhukhov continued to provide real-time interpretation for the International Space Station program. In 2011, TechTrans hired her directly, and she became one of only a small group of TechTrans interpreters that provide continuous space-to-ground mission support for the International Space Station.

When NASA TV began broadcasting Soyuz launches to the International Space Station, the voices of Kozhukhov and her fellow interpreters reached a larger audience. Her interpretations, however, are not tailored for public consumption.

"I would probably not try to say it in words for people who are not directly involved with the program to understand," she said. "We are trying to put it in the same words that the specialist would say."

Kozhukhov was on duty in 2010 for the launch of Soyuz TMA-01M, the inaugural flight of the new M-series Soyuz vehicle. She recalls the flight vividly because a number of minor problems arose during the shakedown of the new spacecraft.

Shortly before launch, Kozhukhov said the pressure inside the capsule increased drastically, prompting Russian controllers to ask commander Aleksandr Kaleri to unstrap himself and access a pressure release valve in the capsule’s orbital module—no easy feat for a cosmonaut lying on his back in a bulky launch suit.

Once the crew finally made it to orbit, things got even more interesting.

"They lost a very vital telemetry on their control panels," said Kozhukhov. Russian engineers spent the entire day troubleshooting the problem without success. Since the crew was scheduled to sleep, the Visiting Vehicle Officers, which are responsible for overseeing incoming ISS spacecraft, called it a night. The Russians, however, decided to burn the midnight oil. During the next Soyuz communications pass, controllers in Moscow asked Kaleri to try some additional fixes.

"The next day, specialists in Houston arrived unaware of the last-minute troubleshooting attempts the Russians undertook the night before," Kozhukhov said. "And it really felt great to have the information that the specialists could use for additional situational cognizance."

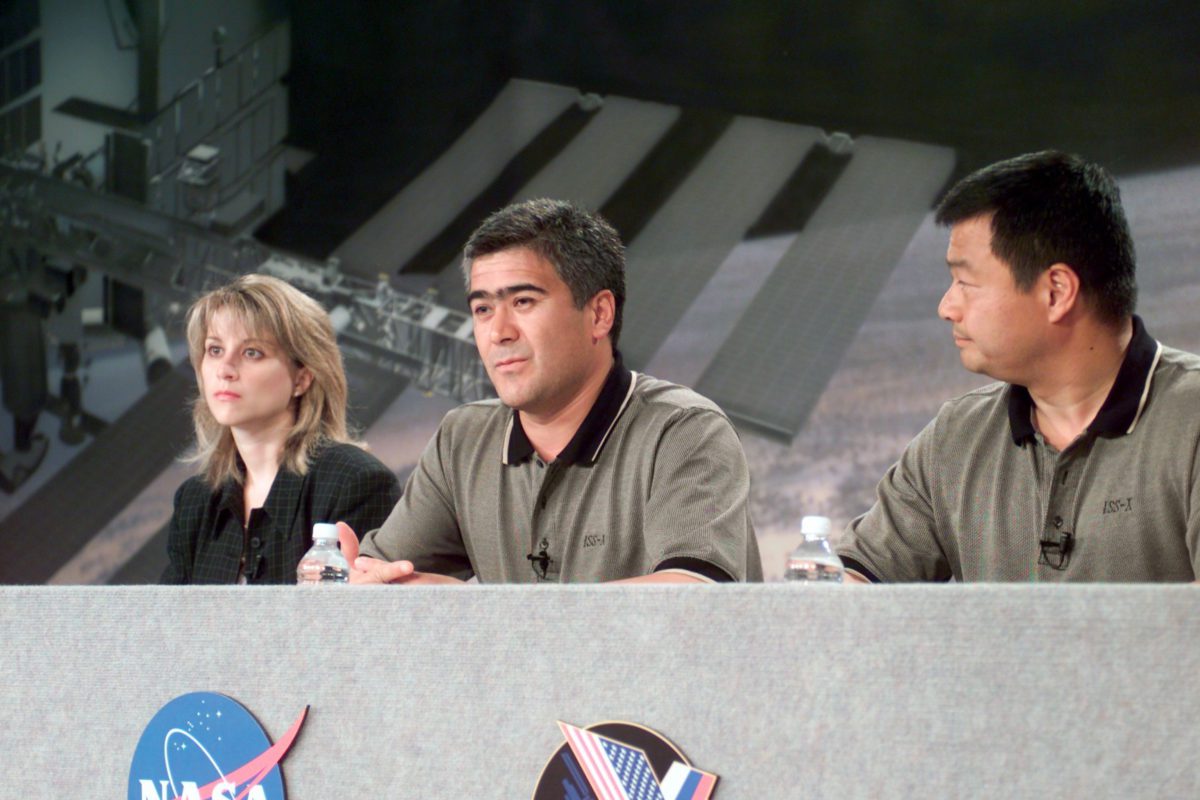

Liftoff of Soyuz TMA-01M Soyuz TMA-01M lifts off, carrying Aleksandr Kaleri, Oleg Skripochka and Scott Kelly into orbit. The 2010 mission was the inaugural flight of the TMA-M series Soyuz spacecraft. Russian interpretations were provided by Elena Kozhukhov.Video: YouTube via collectSPACE / NASA TV

Kozhukhov’s job continues to grow in importance, since NASA has relaxed dual-language requirements early international crews had to meet. Dwindling budgets have contributed to a decline in long-duration language immersion trips for astronauts and cosmonauts. Additionally, spacefarers about to leave Earth for six months are hesitant to leave their families to travel abroad any more than necessary.

Because she has been on the job so long, Kozhukhov is rarely flummoxed by unfamiliar jargon. But occasionally, a stray metaphor will give her pause. She said that current station commander Pavel Vinogradov, for instance, often references rockets, missiles and old Russian movies in his space-to-ground communications.

"We never know what to say,” she said. “You have to explain the whole movie to make people understand the joke.”

One way or another, Kozhukhov and her colleagues are dedicated to getting the message across. Even if that message is, "I'm like a missile. If I'm directed to do something, I will get to my target."

Author's note: the article has been updated to reflect the difference between translation and interpretation. According to this article from the American Translators Association, "translators deal with written words; interpreters deal with spoken ones." However, as the ATA article points out, the dictionary definitions of translation and interpretation do not make this distinction, leading to confusion for those outside the profession.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth