Bill Dunford • Jun 03, 2014

Tracks in the Wilderness

There are places in the American West where you can still see the tracks carved by pioneer wagon wheels more than a century ago. This year I stood on a path in England, still in daily use, that travelers have walked since the days of Stonehenge.

So strong is the human need to blaze trails that we stretch them out everywhere--extending them even to places where our own feet can't take us. You can follow our tracks, in fact, all the way to the deserts of Mars.

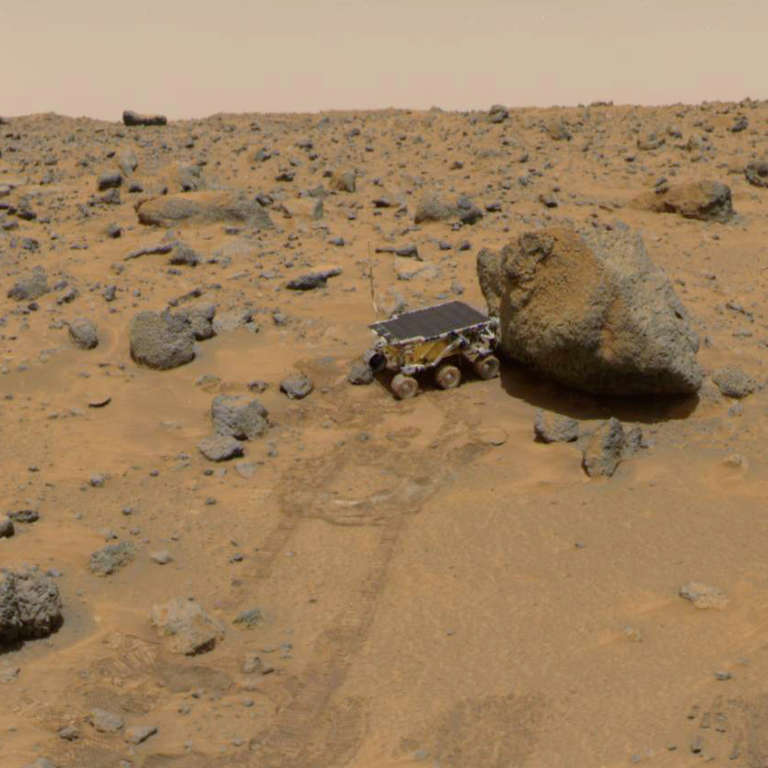

The first people to succeed in making their own trail on the planet were the members of the team behind the Mars Pathfinder mission in the 90's. They earned their mission name by deploying a small, relatively simple rover called Sojourner that opened the way for more sophisticated expeditions. Sojourner was named after another trailblazer, Sojourner Truth.

The next set of robotic pioneers, the Mars Exploration Rovers, traveled much farther on the Martian surface, of course. But they did even more than that, crossing beyond the horizons of their creators' most ambitious plans, literally and figuratively, again and again.

The rover Spirit sent the view below, which tells the tale in a single snapshot. Instead of giving out after a few summer months on the plains inside Gusev Crater, the rover had instead climbed high into the hills, stopping only to winter over in a place that offered relatively good sunlight for its solar panels during the long, dark months ahead. After kilometers of travel, its wheels had begun to freeze up, so it had been driving backward, uphill, dragging one of its wheels through the dirt. Wasting no chance to explore, scientists on Earth had examined the churned material and discovered that it's rich with compounds that hint again that this harshest of deserts was once a watery place.

On the other side of the planet, the Opportunity rover never has stopped driving. Now scaling mountains of its own, it spent most of its life so far sailing across a wide dune sea. Opportunity has proved that it's possible to cross the most distant horizons you can imagine. And then do it again.

While few of the people who first planned these missions ever thought we'd be doing it while Opportunity was still rolling, we also get to ride along with the roving science lab that is Curiosity. We are still in the relatively early days of this mission, and already Curiosity's wheels have laid down tracks over a bed of ancient river stones, among other intriguing landscapes of sandstone, meteorites, and drifting dunes.

The tracks we have made on Mars will fade. I have no idea if the wind will erase the last mechanical "footprints" before the first human ones mark the ground. I have no idea if we will treat Mars better than we have treated the Earth. But I have reasons to hope so. One reason is the fact that these tracks were laid down not by conquerors, but by scientists, people who are incapable of resisting the human need to explore the wilderness, but who have demonstrated the human ability to think through the future, and find that it's a place worth being.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth