Bill Dunford • Jan 13, 2014

Through a Glass, Darkly

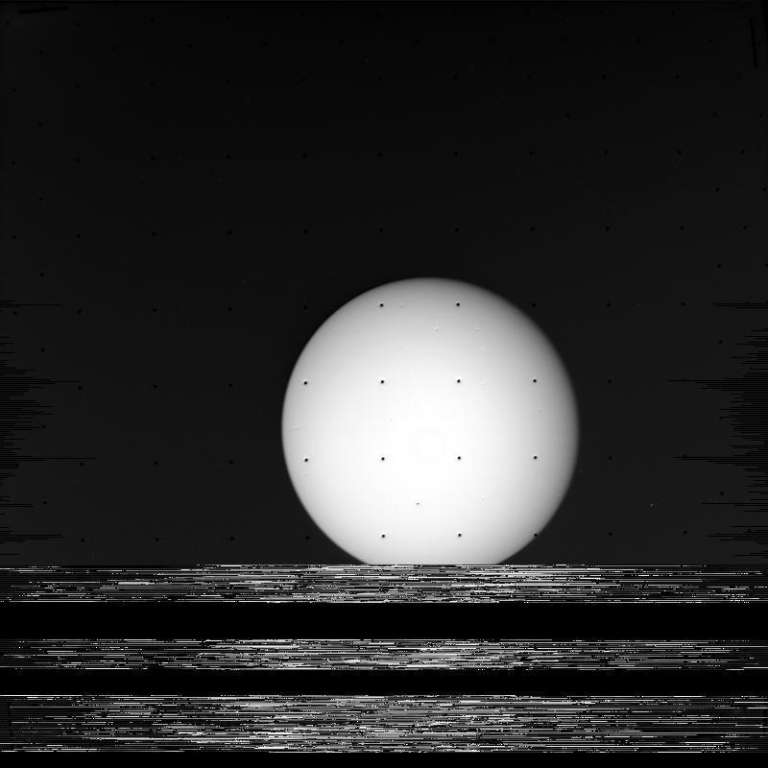

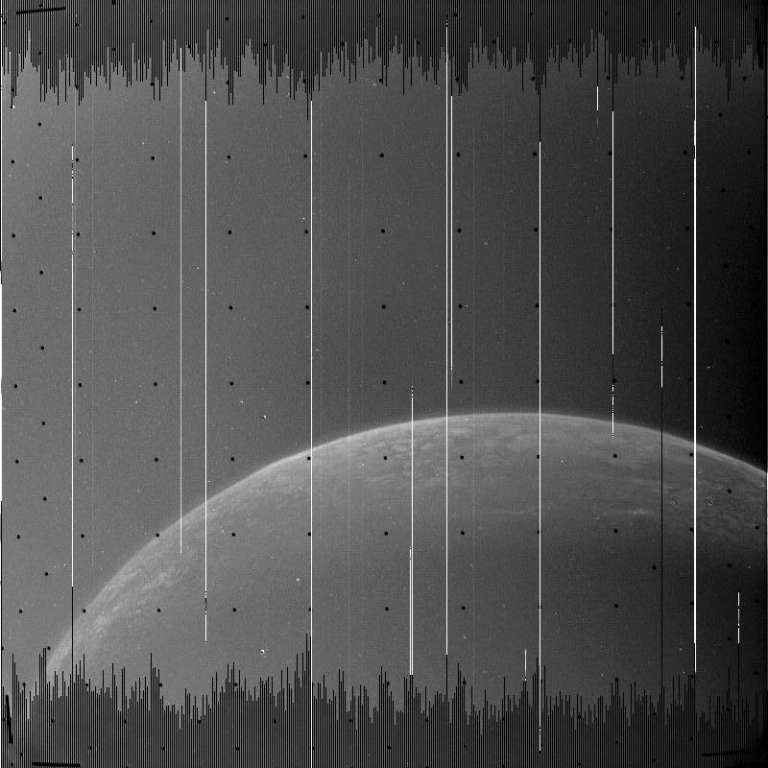

If you've ever tried photography, you know that not every picture can be a prize winner. Sometimes, no matter how carefully you prepare, there's not enough light, or the sun flares in the lens, or the model blinks. Of course, there is some comfort in the fact that even top professionals face the same problems every now and then.

Even when it comes to machines that people have used to create some of the most unforgettable images in history, robotic spacecraft in deep space, not every shot that comes down to Earth is ready for the cover of National Geographic. In fact, some of the better ones still require a little bit of clean-up, whether it's removing a spot of digital noise or correcting color to more closely match what you'd see with your own eye if you could stand on Mars. Some of the pictures are just disasters.

All photography in space faces challenges. Many of these are the usual questions of exposure, framing, and focus, but complicated by extreme changes in lighting conditions, and cameras mounted on platforms that are traveling at thousands of kilometers per hour relative to their subjects. Others problems are endemic to space travel, such as cosmic rays and other forms of radiation interfering with the camera sensor, not to mention the glitches that can crop up in the custom computer systems on board the spacecraft or somewhere else along the line within the Deep Space Network that carries the signals.

Even so, when you're talking about our handsome Solar System, even the throw-away pictures offer their own kinds of rewards. Consider the following set of raw or very lightly processed images that I've come across in the archives. All of them suffer from one photographic malady or another. I'm still glad I saw them.

I'll admit it: I actually like images like these. They remind me that the spacecraft are real. These are not excercises in CGI. They are physical machines of aluminum and silicon, built by human hands, graceful, precise, yet flawed.

They fly through physical space at great speed, beset by storms of radiation and the contstant threat of meteorite impact...or just the wear and tear of travel across millions of kilometers and years of time.

The places they reach are also real. Harsh, unforgiving, but only so because reality itself can be harsh and unforgiving. These are not paintings we're looking at here. It's not a movie. If you could ride with New Horizons, if there were a window where you could press your nose, you could see the glare of the very real Sun in the glass.

Flawed, unprocessed images from space also make me think about the collaboration between human and machine. Who takes a picture of the rings of Saturn: Cassini or the people on the Cassini imaging team? Surely it's some of both. The people who fly the missions overcome terrific technological hurdles just to get the spacecraft to the right place at the right time to make a photograph. When the shots don't quite turn out, it's reminder of how stunning it is when they do.

Besides, just because an image isn't perfectly pretty, that doesn't mean it's not useful. Science and engineering teams can, and routinely do, squeeze knowledge out of every pixel in images that are never widely published.

So I keep looking at these pictures, the throw-aways. I think about the smell of rockets exploded on the launch pad and the silence in a control room after a spacecraft's signal has unexpectedly gone dead. About how we can't help but explore anyway, about the way the imperfect mechanical world reaches out to the sublime natural.

These pictures aren't perfect. But if you look closely you can see ourselves in them.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth