Jamie Carter • Feb 17, 2022

Return to Neptune? The plans to send an orbiter to the elusive planet

Is it time NASA sent an orbiter to study the other blue planet in our solar system? Proposals for missions to study the ice giant planet Neptune and its mysterious moon Triton have been on NASA’s to-do list for over a decade, but nothing has happened until now.

A mission to explore one of the ice giants — Uranus or Neptune — was one of the three priorities set out by the last Decadal Survey in 2010, along with Jupiter’s moon Europa and a sample return mission to Mars. With the Europa Clipper mission due to launch in October 2024 and the Perseverance rover already on the red planet, NASA had made good progress on two of those.

But what about the ice giants?

Reasons to send a Flagship-class mission to Neptune are laid out in two papers: “Neptune Odyssey: Mission to the Neptune–Triton System” and “Neptune and Triton: A Flagship for Everyone.” The latter is one of over 500 white papers now being considered by the National Academies, which will publish in the first half of 2022 its once-per-decade Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey that will make recommendations for NASA missions. Will Neptune feature?

The science case for a return to Neptune

Of all the planets in the solar system, we know the least about Uranus and Neptune.

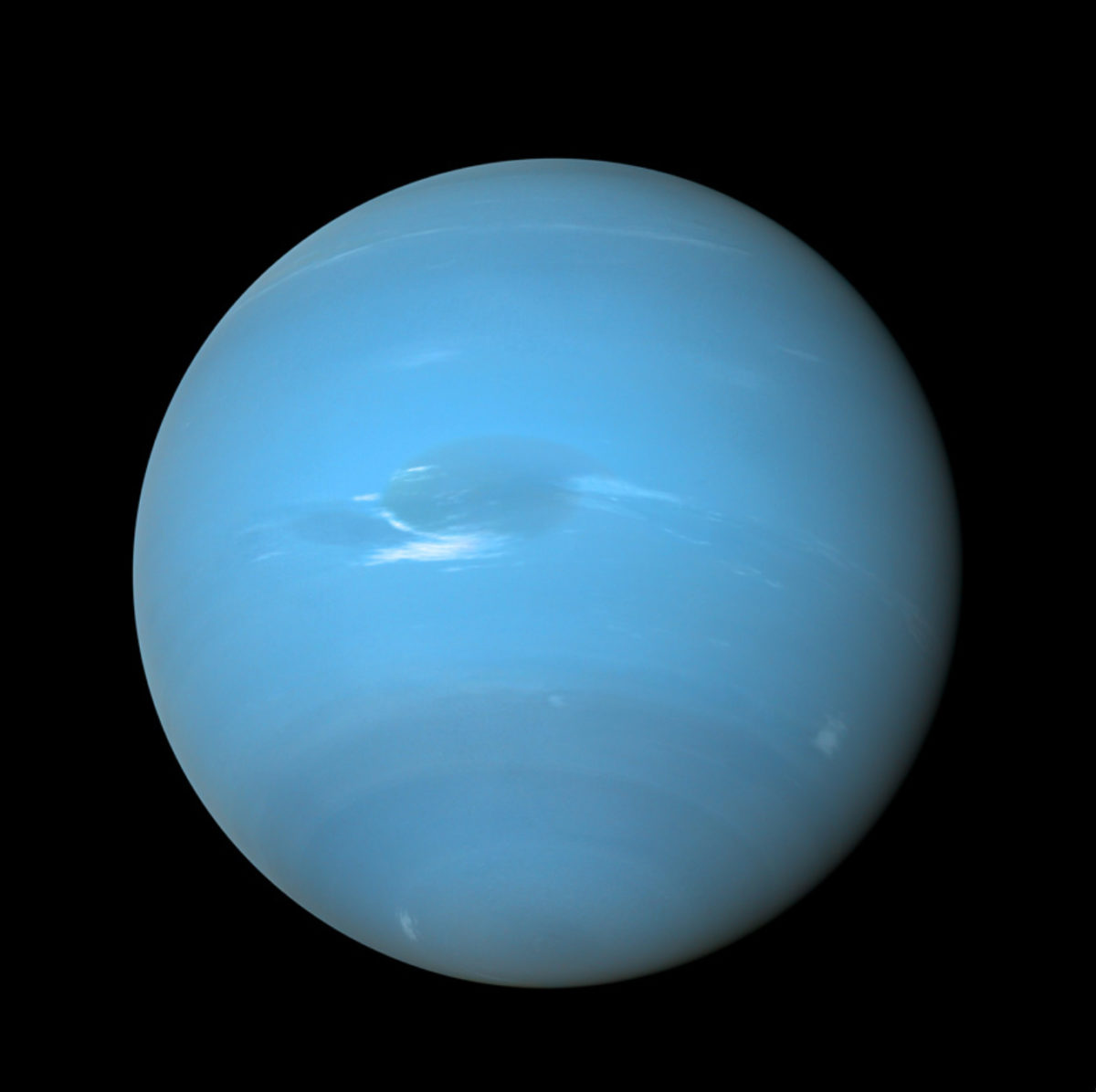

NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft conducted flybys of Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989. It gave us our first and only close-up, discovered six new moons and four rings around Neptune, found a “Great Dark Spot” storm in its blue methane gas atmosphere and saw hints of an underground ocean on its largest moon Triton. Voyager 2’s flyby of Triton was its final act before spinning off into deep space.

No spacecraft has been very close to Neptune since, but the science case for a new mission is mounting. In January 2019, Triton was identified as the highest priority candidate in a paper called “The NASA Roadmap to Ocean Worlds.” Neptune also happens to have the same radius as many of the exoplanets that astronomers are finding elsewhere in the cosmos.

Battle of the ice giants

Many are expecting the Decadal Survey to recommend only a Flagship mission to collect the rock samples now being collected on Mars by the Perseverance rover, but that could be delayed to allow a time-sensitive launch to an ice giant.

Given that there’s also a proposal to send an orbiter to Uranus, why might Neptune be the better target for a big mission?

“One of the problems we have as a community is that we have two ice giants,” said Abigail Rymer, Program Officer at NASA and Principal Investigator for Neptune Odyssey. “We don’t want to choose one and we need to go to both, but the main reason to go to Neptune now is that the plumes observed by Voyager 2 on Triton are in sunlight at the moment at its south pole. That south pole goes into darkness in 2049, but some of the major plumes are still in sunlight into 2060 — so it’s a nice big, wide-open window.”

Triton also helps Neptune’s case.

“Triton breaks the tie between Uranus and Neptune in terms of scientific interest because it’s the only major moon in our solar system that's in a retrograde orbit,” said Dr. Kunio Sayanagi, Associate Professor at Hampton University, who worked on the Neptune Odyssey white paper.

Its orbit makes it almost certain that Triton is a captured Kuiper Belt object in the same size class as the dwarf planet Pluto. Meanwhile, tidal forces are believed to create a deep ocean underneath its surface.

“One of the main reasons for going to Neptune and Triton rather than Uranus is that we get an ice giant and a Pluto-like Kuiper Belt object in one fell swoop,” says Rymer.

Neptune Odyssey: the mission

The Neptune Odyssey mission concept is for a Flagship-class orbiter and atmospheric probe to the Neptune-Triton system.

With a similar design and scope to NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn, the spacecraft would launch in 2031 on NASA’s Space Launch System or a SpaceX Falcon Heavy, get a gravity assist from Jupiter, and arrive at Neptune in 2043 after a 12-year cruise.

If it must launch after 2031, the Jupiter assist won’t be possible; a direct-to-Neptune journey would take 16 years.

“NASA has got the wits to do that if it chooses to, as long as it’s consistent with the timeline that’s decided on for the Mars Sample Return mission,” said Rymer.

When it finally arrives it would go into the orbit of Neptune, simultaneously releasing an atmospheric entry probe that would take 37 minutes to descend. The spacecraft would be equipped with a camera to capture video of the probe falling away into Neptune's atmosphere. It would also have another onboard camera to beam back images just as the Juno spacecraft does at Jupiter.

During its four-year mission, Neptune Odyssey would study the planet, its rings, aurora, small moons and space environment, and fly by Triton multiple times. Eventually, it would plunge inside the rings to perform a final “death dive” into Neptuneʼs atmosphere.

Neptune Odyssey isn’t the only attempt to give NASA a blueprint for a mission to the eighth planet from the Sun. In 2021 NASA toyed with Trident, a proposed Discovery-class mission to conduct a flyby of Neptune and Triton. It would have launched in 2026 to reach Neptune and Triton in 2038. It was passed over in favor of two missions to Venus, DAVINCI+ and VERITAS.

“There were mixed feelings when that wasn’t selected,” said Rymer. “It was so highly rated, and I hope that it’s NASA sending us a message that they want to select something that orbits Neptune.”

Maximizing the science

Something that could make a Neptune orbiter attractive are plans to make it a cross-divisional mission.

“We’re going to carry a camera to take images looking back at our solar system, like Carl Sagan’s “Pale Blue Dot” photo,” says Rymer. “That’s not just an outreach activity — it’s crucial for us to understand what our planet looks like from an astrophysical context in order to understand our observations of exoplanets.”

The long cruise phase could also be used to take measurements of the solar wind.

“We’ve got the Parker Solar Probe close to the Sun and the Voyager spacecraft out in the interstellar medium, so having something that joins those up with 21st-century instrumentation would be very desirable for the heliophysics division at NASA,” said Rymer.

What’s the future for a mission to Neptune? That remains to be seen, but the chance to reveal an ice giant would delight both planetary scientists and exoplanet-hunters. If it can simultaneously explore the solar wind and reveal Triton as a precious ocean world, then a journey to the farthest-known planet from the Sun could be a real crowd-pleaser.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth