Nancy Atkinson • Mar 25, 2021

NASA Mission to Venus in 1978 May Have Detected Phosphine, a Gas Related to Life

A group of scientists say a 43-year-old NASA mission may have detected phosphine and other gases linked to life in Venus’ atmosphere.

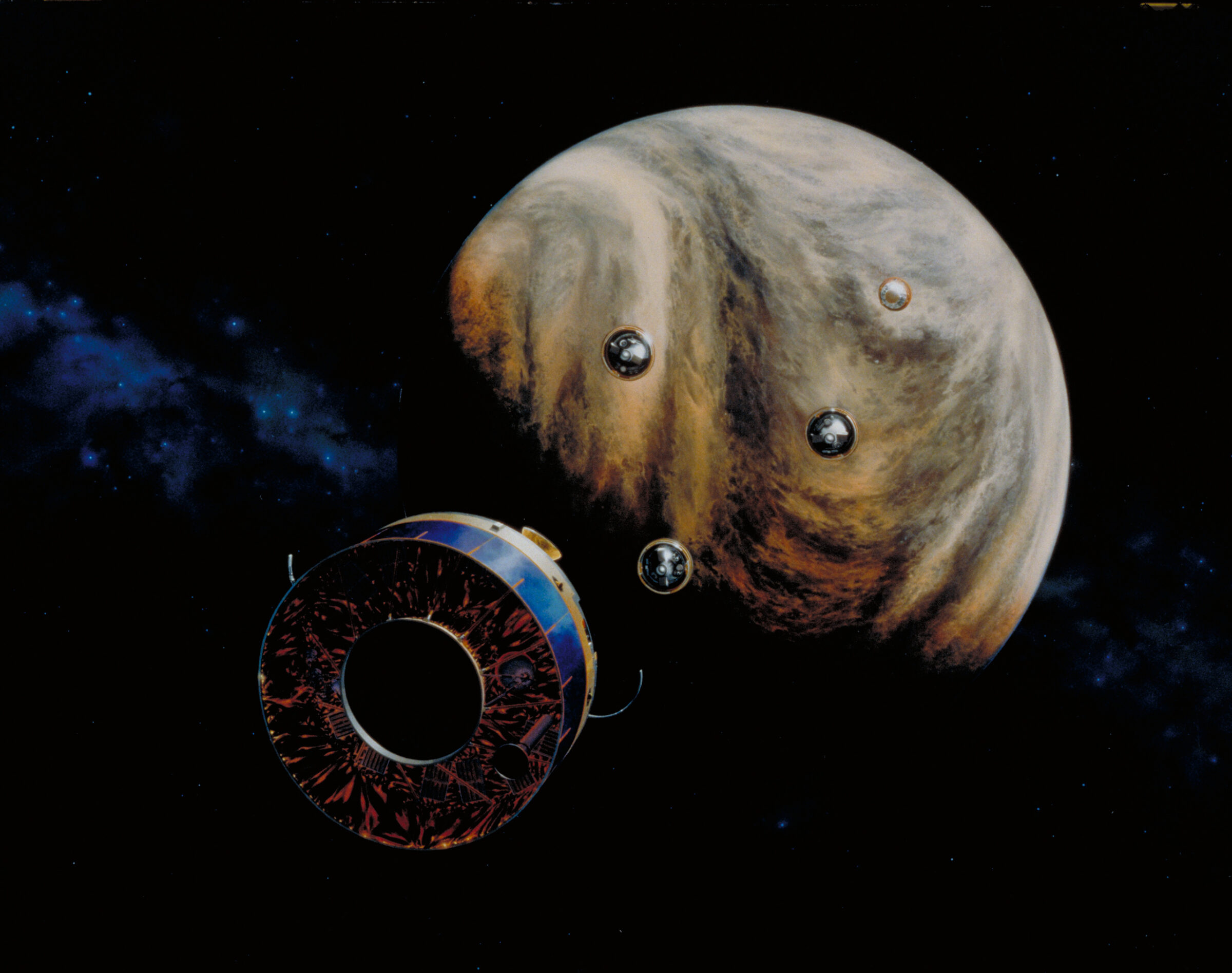

The data come from NASA’s Pioneer Venus Multiprobe mission, which deployed a series of probes into the planet’s clouds in 1978. The findings are the latest salvo in a spirited debate over whether another team of scientists detected phosphine during ground-based telescopic observations in 2017 and 2019.

That discovery, after being announced in 2020, has been questioned by other scientists, with a flurry of papers and studies probing the small amount of available data. The new analysis of the Pioneer Venus Multiprobe data, which was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, is one of the few to provide supportive evidence.

While phosphine itself is not an indicator of life, nothing we know of on Venus could produce it in large quantities. For decades, some scientists have theorized that life could exist in Venus’ atmosphere, where temperatures and pressures are remarkably Earth-like.

The Pioneer Venus Multiprobe findings come from a team led by Rakesh Mogul, a professor of biological chemistry at Cal Poly University in Pomona, California. Mogul’s team examined archival data from the Large Probe Neutral Mass Spectrometer, or LNMS, an instrument on the mission’s largest probe that measured Venus’ atmospheric composition while descending to the surface under parachute.

Mogul’s team says the instrument also found other biologically relevant chemicals, and that part of Venus’ atmosphere is not in equilibrium—meaning a process related to life could be happening there.

Digging through Old Data

The Pioneer Venus Multiprobe data weren’t easy to decipher. At first, Mogul’s team only had some tables in a few old publications. NASA released more archival data from the mission, but Mogul said there was little contextual information, such as ground-based test data from the instrument.

The team sought the advice of Richard Hodges, an original mission team member who helped them see the “data within the data,” Mogul tells The Planetary Society. He added: “It was an honor and a rewarding experience to work with him.”

The 1978 LNMS instrument team focused on the most common chemicals they expected to find at Venus.

“The focus on the minor and trace [chemical] species was minimal—that’s what we realized after looking at the archival data and the associated publications,” Mogul said. “We immediately found signals in data that other publications hadn’t discussed or mentioned. That was all we needed for motivation to keep going.”

Their analysis eventually found that Venus’ middle clouds harbor a phosphorus-bearing gas, with phosphine being the best fit for the data.

“No other phosphorus chemicals fit the data as well as phosphine, especially when considering the mild temperatures and pressures in the middle clouds, where many phosphorus species would not be gases,” said Mogul in a press release.

The data also point to “redox disequilibria,” meaning some parts of Venus’ atmosphere are out of balance. This indicates an active chemical process possibly linked to life may be happening, and supports the notion that Venus’ clouds could provide a safe harbor for microorganisms.

In addition to phosphine, Mogul’s team found hydrogen sulfide, nitrous acid, nitric acid, hydrogen cyanide, carbon monoxide, ethane, and potentially ammonia and chlorous acid. Some of these chemicals could also be linked to biological processes.

While this new look at old data offers exciting evidence, Mogul acknowledges that the debate is far from over. However, this systematic back-and-forth allows the public to watch the scientific process play out in real-time.

“There are always mysteries to be solved and I think what we just showed that sometimes old data can reveal new stories,” Mogul said. “This is all a process, and moving forward is what science is all about.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth