Jason Davis • Jul 13, 2018

NEA Scout unfurls solar sail for full-scale test

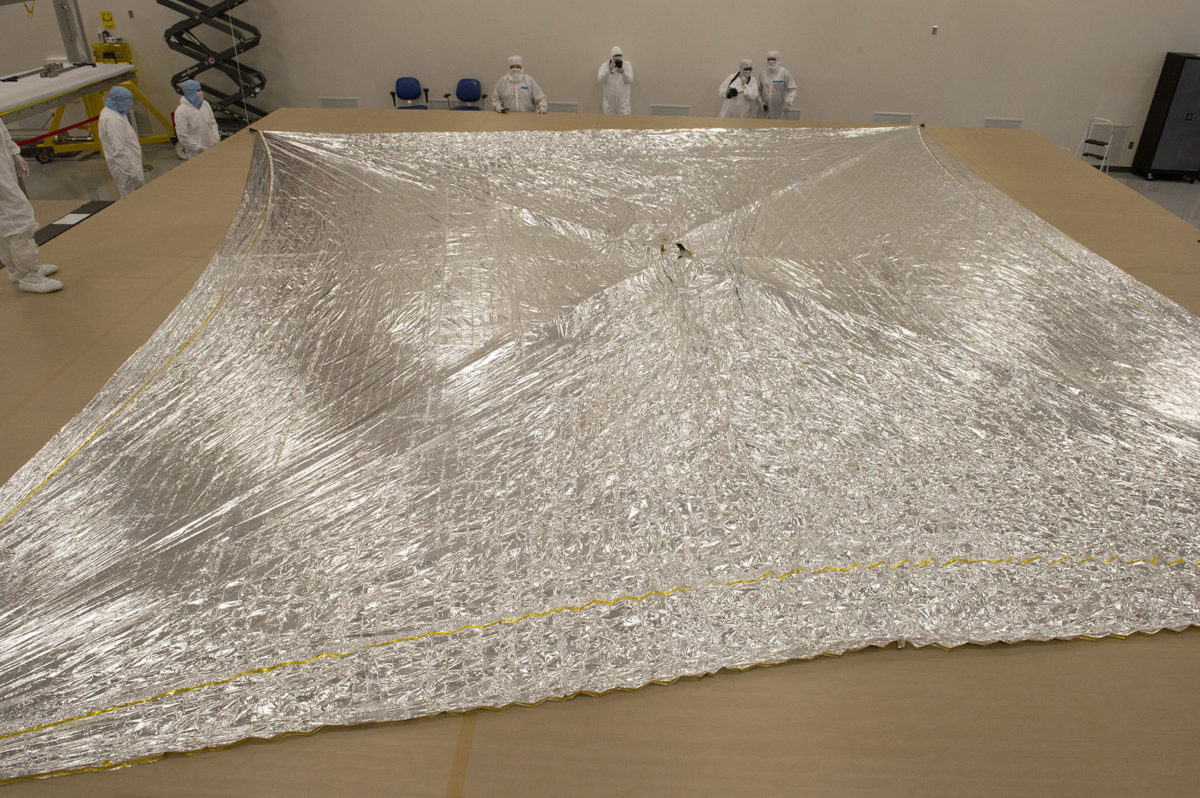

NASA's NEA Scout spacecraft is hitching a ride on the Space Launch System's inaugural flight to lunar space. There, the little CubeSat will deploy an 85-square-meter solar sail and eventually spiral out of the Earth-Moon system to visit a near-Earth asteroid. On June 28, the project completed its first and only full-scale solar sail deployment test at NeXolve, a space materials company near Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

"Everything pretty much went in line with the tests we've had to date," said Tiffany Lockett, a project system engineer for NEA Scout, in a phone interview. "It was as close to a flight-like deployment as we could get."

It's challenging to deploy a space-bound solar sail on Earth, where gravity weighs everything down. Similar to The Planetary Society's LightSail 2 deployment tests, engineers unfurled NEA Scout's solar sail on a large, low-friction table. But since NEA Scout has a bigger sail, the team also used helium balloons to counteract the pull of gravity, and placed the booms on hockey puck-like sliders.

Alex Few, the project's mechanical lead, said it was important make sure any help the team gave to NEA Scout didn't invalidate the purpose of the test: to show that the spacecraft can deploy its sails on its own, in space.

"Seeing the first 30 seconds go smoothly, that was a cool thing," said Few, who can be seen standing on the deployment table in videos from the test. "It was textbook, just how we expected it."

A brief tour of NEA Scout

The above video is the first time I've really seen NEA Scout in enough detail to get a good bearing on its layout. So, what are we looking at? Let's use this GIF from a mission concept video to examine the main components:

NEA Scout is a 6U CubeSat that you can visualize as two 3U LightSails placed side-by-side. The end of the spacecraft that approaches the camera measures 10 by 20 centimeters; behind that is 30 centimeters of spacecraft. Like LightSail, NEA Scout has four deployable solar panels. As you can see in the GIF, the two, skinny, side panels fold out again to triple in size. The white-yellow grid on the top panel is a medium-gain antenna that will be used to communicate with Earth during deep space operations. A second, low-gain antenna is used when the spacecraft is close to Earth.

NEA Scout basically has four internal sections. In the order they approach the camera, they are:

- Thrusters. This section has four, cold gas thrusters used for attitude control and trajectory correction maneuvers.

- Solar sail. Unlike LightSail, which has four, separate, triangular sails, NEA Scout's sail is all in one piece, wrapped around a single spindle and bundled with a layer of kapton nicknamed the sombrero (more on that in a moment).

- Sail booms. There are two, side-by-side boom spindles, each of which holds two, metallic booms wound up like tape measures. A single motor turns both spindles at the same time.

- Avionics. This is the largest section, containing the brains of the spacecraft and a single, visible-light camera that will image a near-Earth asteroid at 50 centimeters per pixel.

For the deployment test, the team only used NEA Scout's solar sail and sail booms sections. They controlled the spacecraft using the flight system board and software, but it wasn't integrated on top of the spacecraft.

Blooms and billows

Lockett and Few said the deployment test gave them confidence that a couple of spacecraft modifications are working as planned.

Prior tests showed that as the sail booms extend, the remaining boom material tends to "bloom" off the spindles, which could gum up the deployment sequence. Few said an easy fix is to stop the deployment and slightly retract the booms, which tightens them back up. The current mission plan calls for doing this automatically when the booms are 70 and 95 percent of the way out.

Another modification involved the packaging of the solar sail. In both LightSail and NEA Scout's case, there is nothing to stop the folded-up sail from billowing out into space once the solar panels open. LightSail's smaller sails are tightly packed into triangular cavities, and generally stay put. But NEA Scout's sail is bigger, and all in one piece, so engineers created a kapton wrapper called the sombrero that holds the sail together like a giant belt. The sombrero has four pre-cut notches with tabs attached. Those tabs are attached to the sail booms with space-grade fishing line, and as the booms extend, the tabs slice the sombrero open, clearing the way for the sail:

Bus stops and next steps

NEA Scout and the other secondary payloads riding the SLS upper stage will be deployed at pre-determined “bus stops” during the cruise to the Moon. NEA Scout gets off at bus stop 1, just outside Earth's outer Van Allen Belt. After an initial lunar flyby, the spacecraft will begin its 20-minute sail deployment sequence.

NASA's secondary payload office has negotiated time for each SLS SmallSat to use the Deep Space Network. Later in the mission, NEA Scout will only check in every 3 days. But during the sail deployment sequence, the team will monitor the spacecraft in real-time—at least, as real-time as you can get when talking to a spacecraft out near the Moon.

NEA Scout's launch date depends on SLS, which is currently slated to launch in late 2019 but could be delayed to mid-2020. The next step for NEA Scout is final assembly. Next comes environmental testing, which should wrap up in January 2019, and in February the team has reserved time to test the spacecraft's communication system with the Deep Space Network. After that, NEA Scout goes to Tyvak, the California-based company that will install it in a SmallSat dispenser. The spacecraft's final stop will be Kennedy Space Center, for integration into one of the slots that ring the inside of the SLS Orion Stage Adapter.

The baseline asteroid NEA Scout will visit is still 1991 VG. But if SLS is delayed too long, 1991 VG will move out of range. Fortunately, there are alternate nearby asteroids the spacecraft can visit.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth