Jamie Carter • Jul 28, 2022

Uranus' mysterious moons: why NASA wants to explore Ariel and Miranda

Is NASA finally going back to Uranus?

If the space agency can finance recommendations in the recent National Academies Planetary Science Decadal Survey then a $4.2 billion Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission could finally help unveil the mysterious ice giant planet — and its extraordinary ocean moons Ariel and Miranda, both appealing prospects in the search for life.

In fact, it’s possible that the most spectacular images sent back to Earth in the mid-2040s will be of dramatic canyons and craters on two of Uranus’ enigmatic ocean moons.

The mission to Uranus

The exciting plans involve a launch in 2031 or 2032 on a commercial heavy-lift rocket — likely a SpaceX Falcon Heavy — before a gravity assist from Jupiter and, after a journey of about 2.9 billion kilometers (1.8 billion miles), arrival in 2044 or 2045.

A probe will be ejected into the planet’s interior while the orbiter will explore the planet’s atmosphere, magnetosphere, and moons. Planetary scientists are particularly interested in learning more about a group of Uranus’ moons.

“Close-up exploration of Uranus’ five large moons with a magnetometer, near-infrared mapping spectrometer, and visible and mid-infrared cameras would provide critical information on the spectrum of ocean worlds in our Solar System,” said Richard Cartwright, a planetary scientist and astronomer at NASA Ames Research Center.

Why the moons of Uranus are so exciting

Ariel, Miranda, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon are the five largest of the Uranus System's 27 moons.

“Uranus’ large moons are really weird,” said Cartwright. “They are all candidate ocean worlds that may have internal saltwater oceans, perhaps similar to Ceres and Enceladus — and they may have harbored life in the past.”

Those five largest moons have dark but surprisingly young surfaces that could be rich in organics — the building blocks of life as we know it. They also appear to be geologically active.

“They display evidence for recent geologic resurfacing, including possible cryovolcanic activity and high internal heat,” said Chloe Beddingfield, a planetary scientist and astronomer at NASA Ames Research Center and leading expert on Uranian moon geology. “Investigation of these moons would enhance our knowledge of where potentially habitable bodies exist in our Solar System.”

What Voyager 2 saw

All five moons — and some of Uranus’ other 22 moons — would likely be imaged by a flagship mission. For some, though, it wouldn’t be the first time.

“The snapshots of the Uranian moons’ surfaces collected during Voyager 2’s brief flyby in 1986 revealed ubiquitous evidence for endogenic geologic activity, in particular on Ariel and Miranda,” said Cartwright. Endogenic activity is planetary scientist-talk for plate tectonics, which may have occurred recently on these two moons.

Named after characters in William Shakespeare’s play “The Tempest,” Ariel and Miranda are similar in size to Enceladus. Both have surfaces that appear to have been fractured and then resurfaced by water and ammonia-rich lavas. That suggests internal heat. However, there are some major differences between Ariel and Miranda.

Ariel: canyons and cryovolcanism

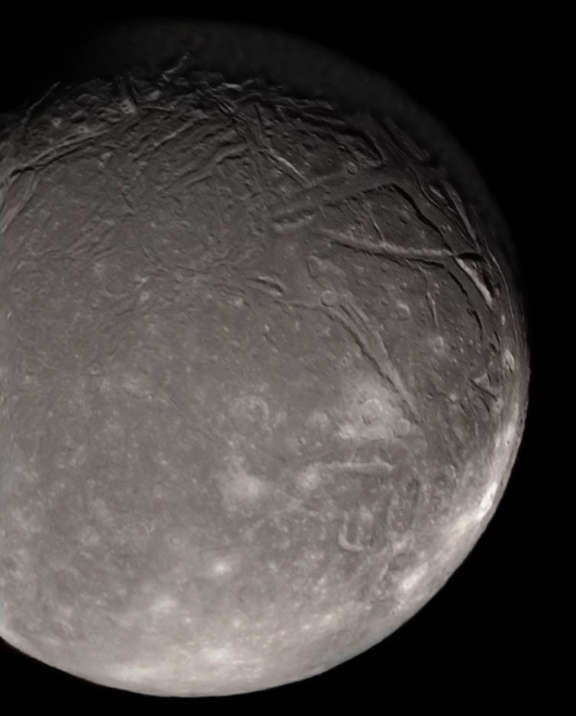

According to Cartwright, Ariel is not only the “most interesting moon,” but the “best target for improving our understanding of ocean worlds.”

Dominated by chasma — large canyons — there’s plenty of evidence on Ariel for a changing surface that might be caused by an underground ocean. Its surface is rich in carbon dioxide ice and is also thought to host ammonia and carbonates. It’s possible that Ariel has or had a subsurface ocean with ocean materials that reached the surface. According to Beddingfield, Ariel has features that may have formed from cryovolcanic ice flows while its large canyons appear to have fissures reminiscent of volcanic activity.

Miranda: craters and ‘coronae’

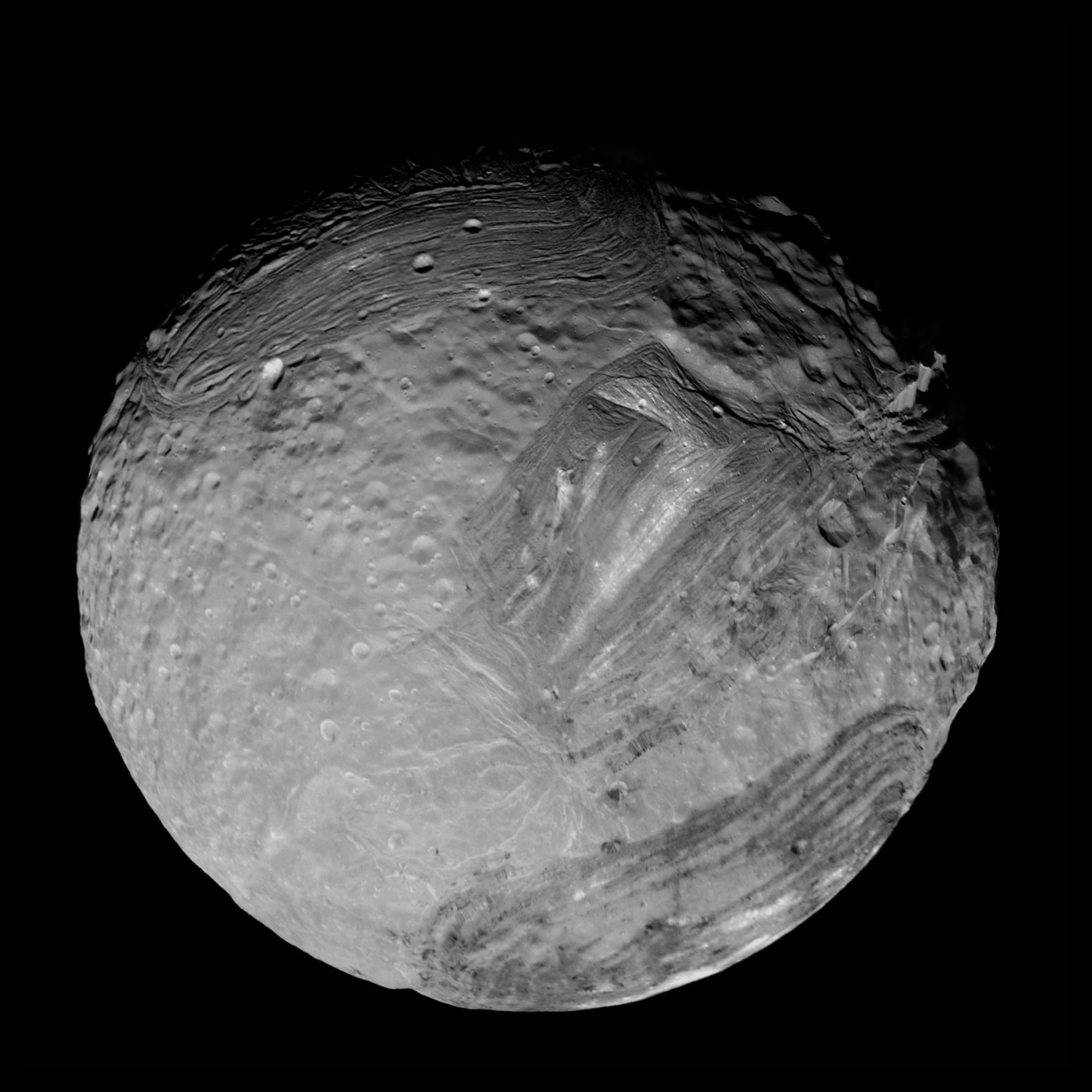

An ancient terrain pockmarked with craters that have smooth floors, Miranda is one of the oddest-looking objects in the Solar System. It reminds planetary scientists of both the Moon and Enceladus.

“Many craters on Miranda are heavily mantled with regolith that may indicate a plume-driven mantling process like that observed on Enceladus,” said Beddingfield.

Water is known to exist on Miranda’s surface and it’s suspected that it also hosts methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, or nitrogen. It’s also got three mysterious polygonally shaped areas called coronae amed Arden, Inverness and Elsinore. It’s thought they’re caused by warm ice rising to cause tectonic faults that deform the moon’s surface, and there are possibly many more.

Revealing the Uranian satellites

What we know so far about the Uranian satellites is at best only half the story because we only have images of the moons’ southern hemispheres. “The northern hemispheres of the Uranian moons were shrouded by winter darkness at the time of the flyby and were largely unimaged, leaving many unanswered questions about the origin and evolution of these icy bodies,” said Cartwright.

That’s why a Uranus mission must go as soon as possible. Since Uranus orbits the Sun every 84 years, arriving at Uranus in the mid-2040s would mean a good view of the moons’ southern hemispheres. It will also give planetary scientists a chance to watch seasonal changes as the Uranus System approaches winter.

Are the moons being bombarded?

A flagship mission will also investigate how the moons interact with Uranus’ magnetosphere. In advance of that Cartwright is engaged in observations of the four largest moons — Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon — using both the Hubble Space Telescope and, shortly, the James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRSpec instrument. The observations are studying whether the surfaces of the moons are being bombarded with charged particles trapped in Uranus' magnetosphere.

“As we have seen in the Jupiter and Saturn systems, charged particle irradiation of icy moon surfaces is an important, ongoing source of surface modification that we need to study with instruments on a Uranus orbiter to better understand the chemical evolution of Uranus’ moons,” said Cartwright. “The results of our JWST investigation will help shape the science goals and spectroscopic objectives of a Uranus orbiter mission.”

A flagship mission to the Uranian system will provide an incredible opportunity to explore how ice giant systems — a common kind of exoplanet, it turns out — formed and evolved. However, it will also allow planetary scientists to answer fundamental questions about how Uranus migrated through the Solar System and, most excitingly, whether its classical moons — and particularly Ariel and Miranda — are ocean worlds that may harbor life.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth