Nancy Atkinson • Oct 08, 2020

Meet Orbilander, a Mission to Search for Life on Enceladus

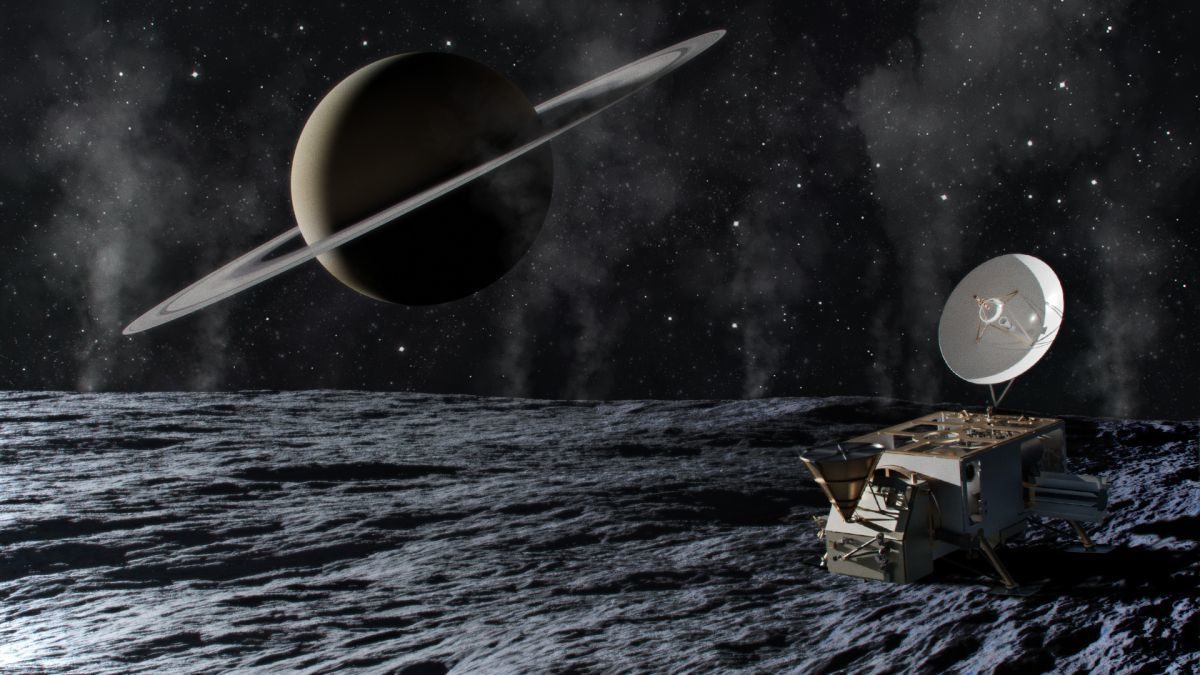

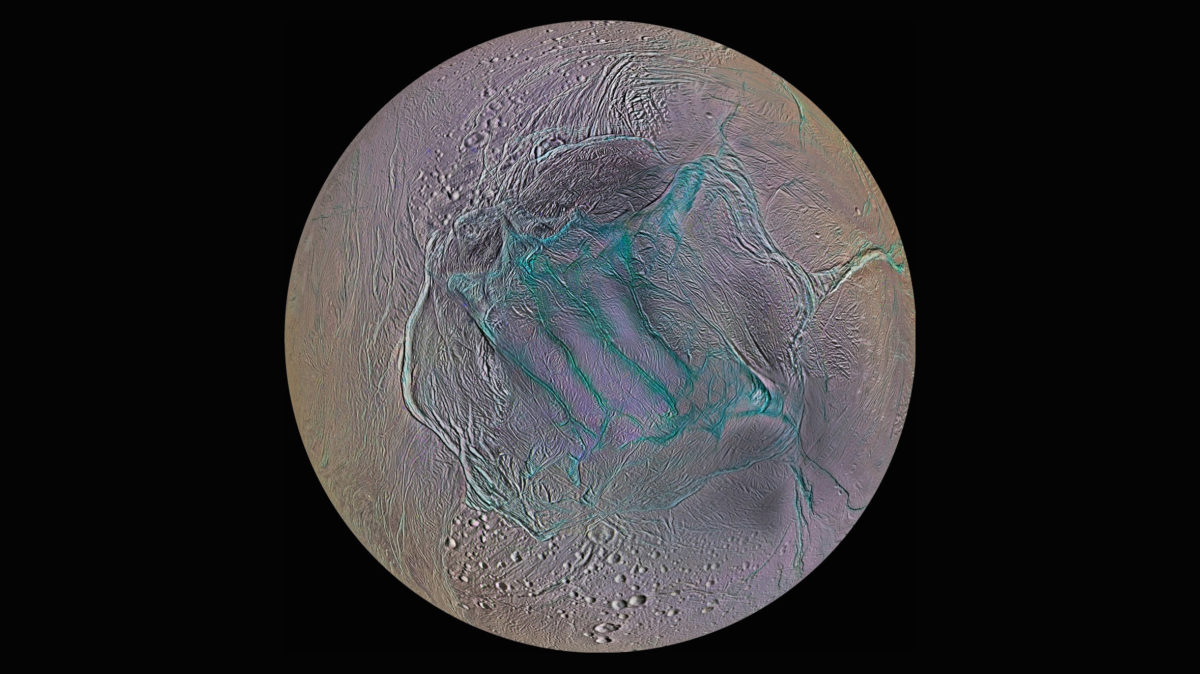

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft left a legacy of discoveries behind when its 13-year-mission to Saturn ended in 2017. One of the biggest findings: the icy Moon Enceladus has a subsurface ocean that vents water into space. Fissures slashed across the south pole have temperatures warm enough to suggest the ocean is being heated by the moon’s core. On Earth, similar spots called hydrothermal vents are hotspots for life.

A team of scientists and engineers at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland are pitching NASA a mission that would take a closer look. It’s called Orbilander—named for its ability to function as both an orbiter and a lander. Orbilander’s mission is geared towards a single question: is there life on Enceladus?

“We know there is a subsurface ocean, and we have every reason to suspect it is habitable,” said Shannon MacKenzie, a planetary scientist and the lead author of the Orbilander mission concept study. “We have the technology to go and sample it, thanks to the plumes.”

Many Cassini mission scientists have endorsed the idea of an Enceladus followup mission. While previous Enceladus concepts have been pitched for NASA’s lower-cost Discovery and New Frontiers programs, MacKenzie’s team is calling for a flagship mission with a price tag of $2.5 billion. Orbilander is a flagship mission concept being studied for the next planetary science decadal survey, a community-authored report produced every 10 years to guide NASA mission priorities.

“The Enceladus community went into this program of mission concept studies assessing what a flagship mission to this moon would look like, especially if we focused on the next—and I would argue, obvious—science question at Enceladus: is it inhabited?” MacKenzie said.

An Orbiter and a Lander

Orbilander would start by orbiting Enceladus for approximately 200 days—no simple task with Saturn’s giant gravity field next door. The team plans to rely on station-keeping maneuvers developed for other missions and choose orbital trajectories that balance spacecraft health with science return.

Despite their brilliant appearance in Cassini images, Enceladus’ plumes are not very dense: Orbilander will be flying through something more like a cloud than a garden sprinkler. Particles from the plumes will funnel into science instruments at high speeds as the spacecraft zips along, requiring the team to devise ways to gently decelerate them so they aren’t pulverized.

A lot of the time in orbit will be spent looking for the right place to land. Despite Cassini’s extensive surveillance of Saturn and its moons, there isn’t enough high-resolution topography data available for Enceladus’ south pole.

“We have the time in our schedule to not only acquire that data, but also send it back to Earth to give the scientists time to digest the data and perhaps have some passionate discussions about which landing sites are the best,” said MacKenzie.

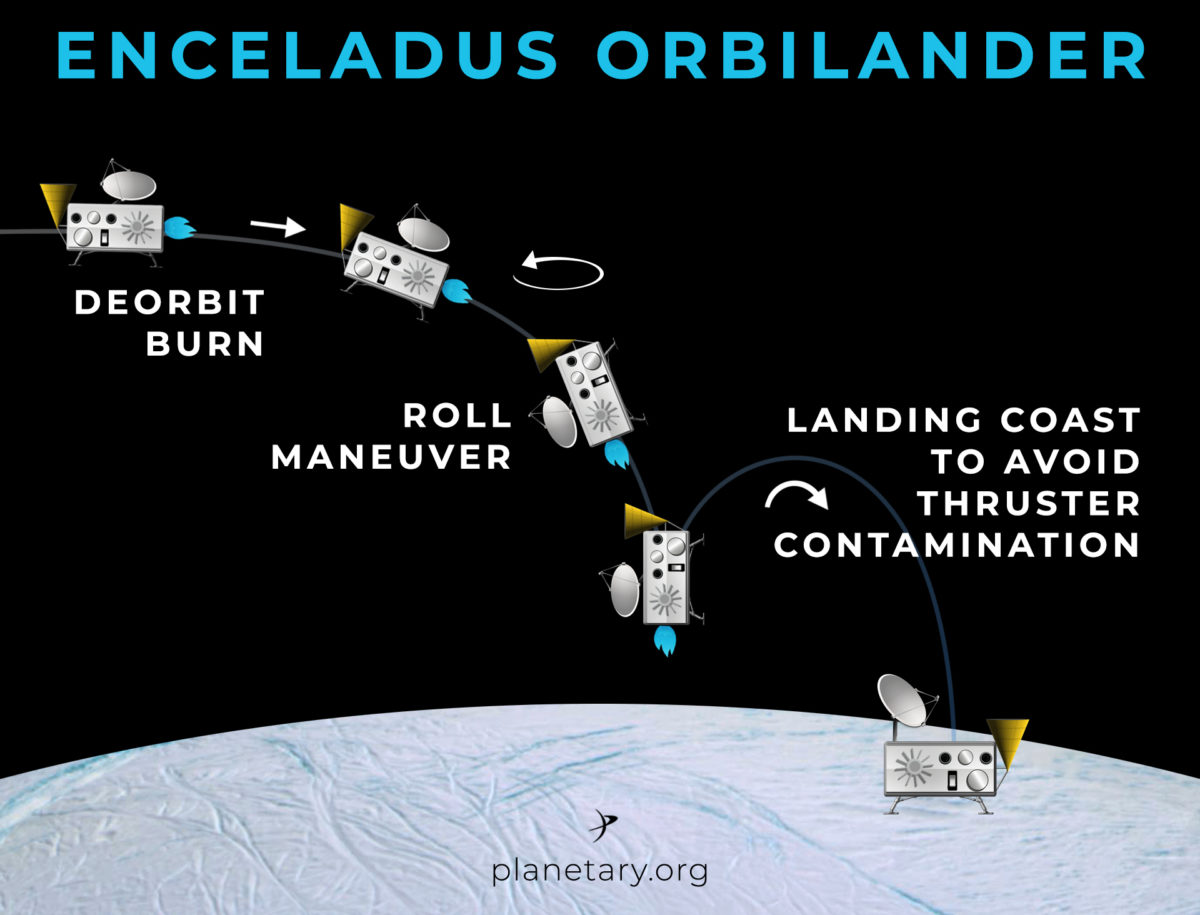

Once a location is found, Orbilander would turn on its side and convert to a lander. It would descend using terrain-relative navigation similar to what OSIRIS-REx will use to capture a sample from asteroid Bennu, and what the Dragonfly mission to Saturn’s moon Titan will use to fly around the surface. Two nuclear power sources will keep Orbilander running surface for up to a year and a half.

No Single Life Detection Instrument

Orbilander would rely on a complex suite of instruments to determine whether Enceladus’ water has a blend of chemicals conducive for life as we know it, and search for amino acids, lipids, and cells. The instruments include mass spectrometers to weigh and analyze molecules, a seismometer, a microscope, and a DNA sequencer. For remote sensing, the spacecraft would have cameras, radar sounders, and a laser altimeter.

“It would be great if there was an instrument called ‘the life detection instrument,’ and after feeding it a sample, the instrument yielded an unambiguous result whether life was detected,” said MacKenzie. “But such a thing does not exist, so we came up with 6 different instruments that provide indications of several different biosignatures. That way, the end result is more compelling than a single detection.”

Unlike most other moons with subsurface oceans, Enceladus’ geysers offer a unique opportunity to sample the water without having to drill through the surface. Not only will Orbilander access the plumes by flying through them in orbit, it will also capture plume material falling back to the surface after the spacecraft lands.

Worth the Wait

If endorsed in the upcoming decadal survey and selected by NASA for development, Orbilander wouldn’t launch until 2038 and arrive at Enceladus until at least 2050. Part of that is driven by budget constraints—there’s only so much money to go around—but that’s also when Encleadus’ south pole will be in sunlight.

That’s a long time to wait, and the final design of the spacecraft would likely change from the possibilities presented in the concept study. But for MacKenzie, it’s a chance to make one of the biggest scientific discoveries of all time.

“It’s just an opportunity waiting for us to take advantage of,” she said. “I can’t think of a better place in the solar system to do the search for life in the near-future.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth