Jason Davis • May 06, 2024

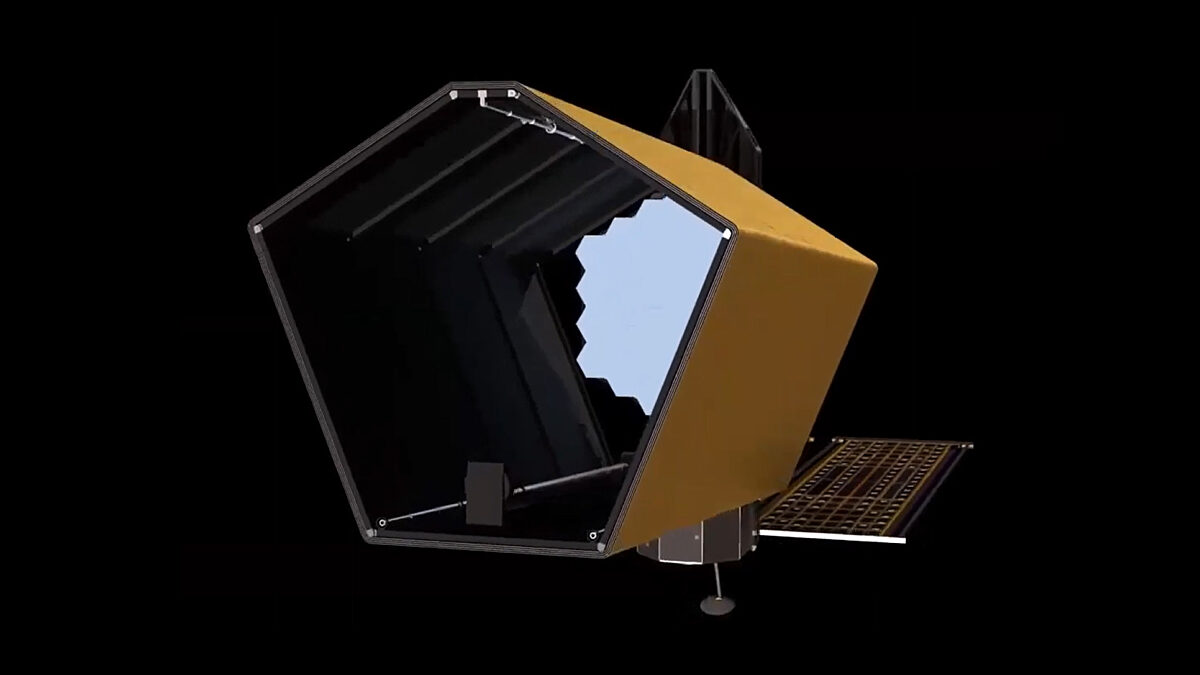

Meet the Habitable Worlds Observatory, NASA’s life-seeking telescope

A powerful new space telescope could help us answer the question of whether or not we are alone in the Universe.

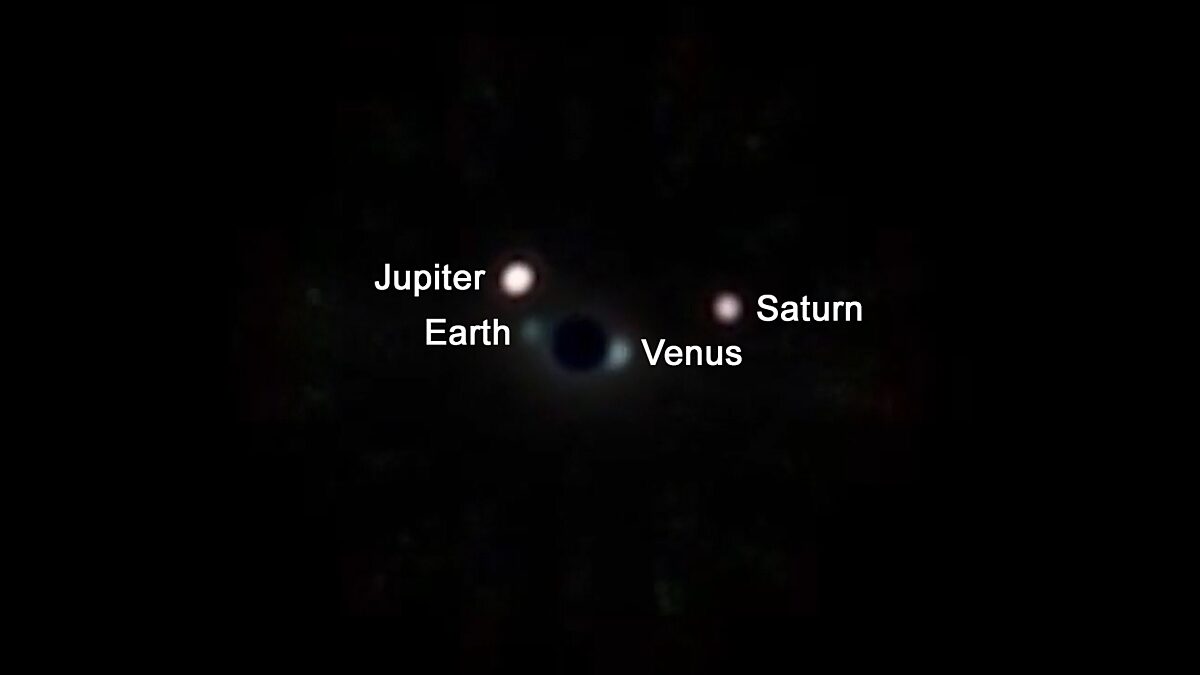

NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory, or HWO, is a “Super Hubble” telescope that would directly image Earth-size exoplanets circling other stars. Using a JWST-size mirror and ultra-precise optics, HWO would scrutinize the atmospheres of these worlds for signs of life.

“It's the first observatory really designed around characterizing exoplanets as complex worlds, and not just as discovering them as point sources,” said Giada Arney, a member of the Science, Technology, and Architecture Review Team for HWO at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “That's really exciting for me as a planetary scientist.”

More than just a life hunter, HWO is designed to be a multipurpose observatory like Hubble and JWST. The telescope will study what drives galaxy growth and trace the origins of elements and molecules in the early Universe. It would also monitor worlds much closer to home.

“I'm excited about the possibility of observing our Solar System's ocean worlds, such as Neptune's moon Triton and Jupiter's moon Europa,” said Lynnae Quick, an ocean worlds planetary scientist at Goddard. “HWO could be instrumental in helping us learn more about volatile cycling on Triton as the seasons change there,” she said.

Building a next-generation observatory to hunt for life and advance our understanding of the Cosmos will be a challenging and costly project. The telescope would not launch until at least the early 2040s. But it will be worth the wait.

A capable coronagraph

No one knows what HWO will look like, as the telescope is still in its early design stages. But some basic requirements are already in place, thanks to the 2020 astrophysics decadal survey, a community-authored report that sets priorities for NASA’s next 10 years.

HWO would have a mirror about the size of JWST’s and be positioned at the same location: the second Lagrange point, a gravitationally stable spot located 1.5 million kilometers (1 million miles) from Earth.

Like Hubble, HWO would be serviceable, meaning future astronauts could journey to the telescope for repairs and upgrades. Also like Hubble, HWO would gather light in shorter, visible and ultraviolet wavelengths, where certain biosignatures are more pronounced. Shorter wavelengths also work best with a key piece of technology needed to directly observe exoplanets: a coronagraph.

Coronagraphs are used to block the light of stars, revealing fainter nearby objects. Imaging an exoplanet is like searching for a firefly next to a spotlight. Seeing smaller, Earth-size planets will require the most advanced coronagraph ever built.

“We need a coronagraph that is thousands of times more capable than any prior space coronagraph,” said Arney. “We also need an optics system that is exquisitely stable.”

A technology demonstration coronagraph for HWO will fly on the upcoming Roman Space Telescope. Rather than blocking a star’s light with a disc, Roman’s coronagraph uses a series of mirrors and masks to separate light from an exoplanet from that of its host star. The mirrors are so precise that they can make adjustments smaller than the width of a strand of DNA.

As extraordinary as that sounds, the requirements for the optics within HWO’s coronagraph may be even stricter, requiring corrections on the order of tens of picometers, smaller than the width of an atom.

Interpreting the results

HWO will examine the atmospheres of at least 25 potentially habitable worlds, searching for biosignatures that could indicate the presence of life.

The detection of biosignatures requires context, so that we can avoid being fooled by non-life processes. Key Earth biosignatures sought by HWO will include oxygen, ozone, and methane, though others are also under consideration. Scientists will have to apply what they know about the planets and moons in our own Solar System to interpret the conditions on the exoplanets HWO observes.

“That type of ‘ground truth’ is very important when we're looking for life,” Quick said. “In order to understand how prospects for life on Earth-like exoplanets may be affected by geological processes at their surfaces, we must first understand how geological processes on Earth and potentially habitable bodies in our Solar System, such as Europa, Mars, and Titan, have affected their suitability to harbor life over time.”

Conceptual work on HWO is proceeding through two teams: START (Science, Technology, Architecture Review Team), which is working on the telescope’s science objectives, and TAG (Technical Assessment Group), which is working on technical requirements.

In official NASA parlance, the project is in its pre-formulation phase. A project office at NASA Headquarters is expected to be established this year, which will move HWO into a “pre-phase A” status.

It will take years to mature the technologies needed to build HWO and get the telescope ready for launch. But one day in the not-so-distant future, the observatory could train its eyes on a star system not unlike our own, and pick out the first signs of life on another world.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth