Asa Stahl • Aug 12, 2024

Mars may host oceans’ worth of water deep underground

Scientists have found tentative evidence of liquid water in Mars — that’s right: not on Mars, but in it.

New results suggest there are huge amounts of water locked far beneath the planet’s surface, enough to cover Mars with an ocean at least a kilometer deep. If confirmed, the discovery would transform our understanding of Mars’ past and hint at a habitat where life could potentially thrive there today.

What lies beneath

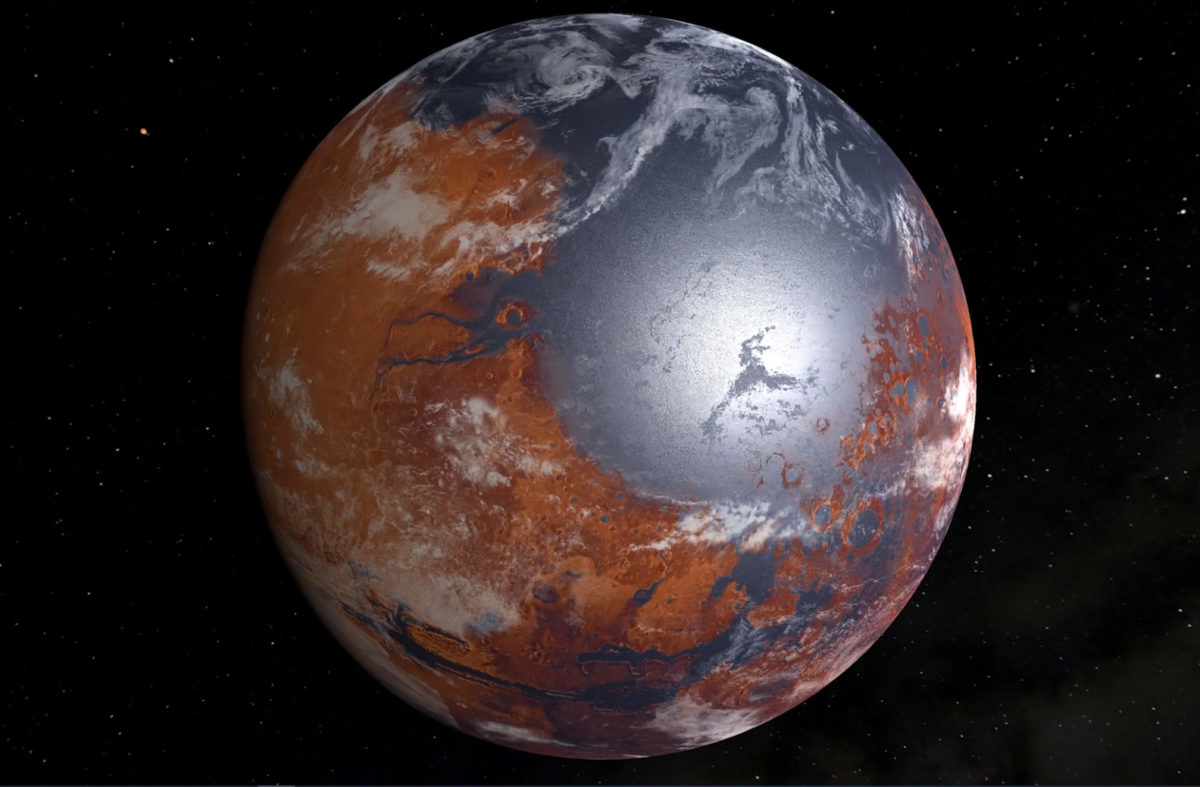

Billions of years ago, water flowed in Martian lakes, rivers, and possibly even an ocean. Then something happened to dry the planet and leave its surface the way we see it today: icy, but perhaps without a single drop of stable liquid water.

The most accepted explanation is that most water on Mars was lost to space. For years, though, some scientists have questioned whether that would have been enough to completely dry Mars, especially if the planet once had enough water to fill oceans. And if not all water went up into space, that would leave only one other direction: down.

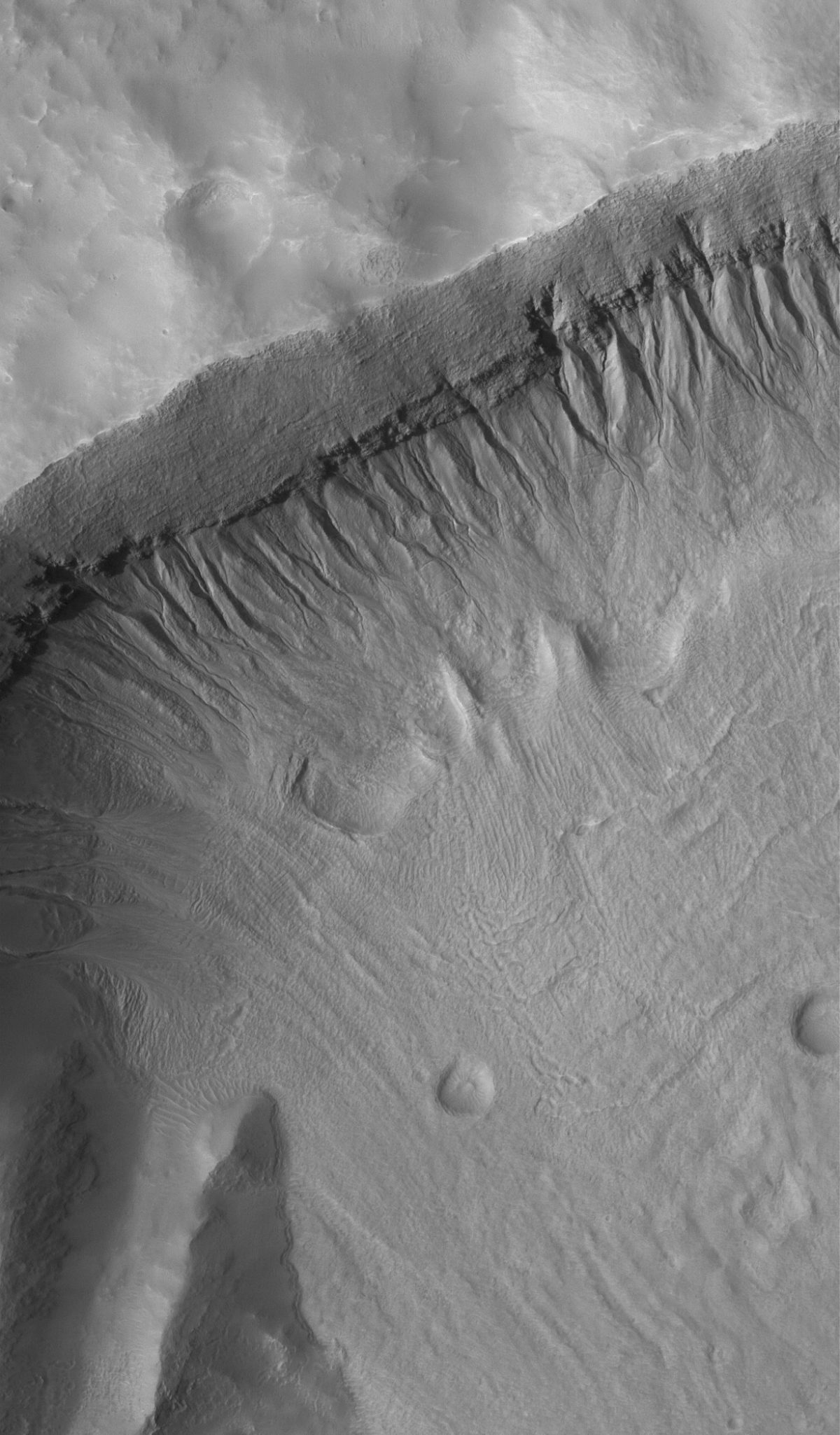

Now, a team of scientists has used Marsquakes — measured by NASA’s InSight lander years ago — to see what lies beneath. Since the way a Marsquake travels depends on the rock it’s passing through, the researchers could back out what Mars’ crust looks like from seismic measurements. They found that the mid-crust, about 10-20 kilometers (6-12 miles) down, may be riddled with cracks and pores filled with water. A rough estimate predicts these cracks could hold enough water to cover all of Mars with an ocean 1-2 kilometers (0.6-1.2 miles) deep.

“That’s a lot of water,” said Vashan Wright, lead author of the study and professor of geophysics at Scripps Institute for Oceanography.

This reservoir could have percolated down through nooks and crannies billions of years ago, only stopping at huge depths where the pressure would seal off any cracks. The same process happens on our planet — but unlike Mars, Earth’s plate tectonics cycles this water back up to the surface.

The weather underground

On Earth, these water-filled rocks can host microbes even while buried deep in the crust, said Michael Manga, study author and professor of planetary geology at the University of California at Berkeley. Since liquid water is one of the basic requirements for life as we know it, does that mean Mars could also host microbes underground?

“That’s the bazillion-dollar question,” Manga added.

If life ever existed near the surface of Mars, microbes could have survived by following the water down through the crust. That would require habitable conditions to have stretched to great depths for at least some time. To serve as a habitat, rocks in the mid-crust would also need to host organic molecules and a source of energy.

Unfortunately, it’s doubtful scientists will be able to plumb these depths anytime soon.

“It would be very challenging,” Wright said. Only a few projects have ever bored so deep into Earth’s crust, and each one was an intensive undertaking. Replicating that effort on another planet would take lots of infrastructure, Wright goes on, and lots of water.

But there may be other ways to find out more. If groundwater on Mars has been pushed to the surface in certain places, exploring them could provide a window into the environment underground. Future missions like Mars Sample Return could also drastically change what we know about the history of Mars and its water.

In the meanwhile, the researchers will continue to piece together this puzzle.

“Our best explanation is that there’s water,” said Manga, “but it’s only the best explanation.” There are still open questions — for example, if there’s so much water in the mid-crust, why don’t they see an ice layer on top of it? Exploring these questions could lead to new ideas.

Or, after years of asking, “Is there life on Mars?” we might begin asking another question, too:

“Is there life in it?”

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth