Bruce Betts • Nov 14, 2022

LightSail 2 is about to burn up

After 3.5 years, 18,000 orbits of the Earth, and 8 million kilometers (5 million miles) traveled, The Planetary Society’s successful LightSail 2 solar sail spacecraft will burn up as it reenters the Earth’s atmosphere in the next few days. We always knew this would be the eventual fate for the spacecraft. It’s actually taken longer than originally predicted.

Despite the sadness at seeing it go, all those who worked on this project and the 50,000 individual donors who completely funded the LightSail program should reflect on this as a moment of pride.

The Planetary Society will be providing another update once the deorbit is complete, but in the meantime here is a full description of what’s happening with the spacecraft right now and what will come next.

LightSail 2 in a Nutshell

The LightSail program has consisted of the LightSail 1 test mission and LightSail 2 mission. During its one-year primary mission, LightSail 2 accomplished its main technical goal, becoming the first small spacecraft to demonstrate controlled solar sailing, using only sunlight reflecting off the sail as propulsion to change its orbit.

During its extended mission and through its second year in orbit, LightSail 2 continued to teach us more about solar sailing and even achieved more efficient sailing. The mission’s third year saw its most effective solar sailing, followed by an increase in atmospheric drag from increasing solar activity. The spacecraft has continued working throughout its three-and-a-half years in orbit.

LightSail 2 also achieved its other mission goals, which include involving and exciting Planetary Society members and the general public in space exploration, and demonstrating and raising awareness within the space technology community of solar sailing as a viable propulsion technique.

A successful technical demonstration helps open the door for future solar sailing missions to be taken more seriously and can aid their potential for selection to fly. We are delighted to see three NASA missions as well as other missions in the works that will take the next steps forward including Near Earth Asteroid (NEA) Scout, which is currently awaiting launch inside the SLS rocket scheduled to launch the Artemis I mission on Nov. 16, as of this writing. Depending on the timing of everything, there may be no gap in having a solar sail mission in space.

Drag is a Real Downer

Atmospheric drag is the culprit bringing LightSail 2 down. The effect gets larger as a spacecraft goes lower because atmospheric density increases, and quite rapidly. This can be hard to imagine since we typically think of space as being hundreds of kilometers above the Earth. Although this is true, there are still particles of atmosphere up there and when a spacecraft hits them going some 28,000 kilometers per hour (about 17,000 miles per hour), they slow it down.

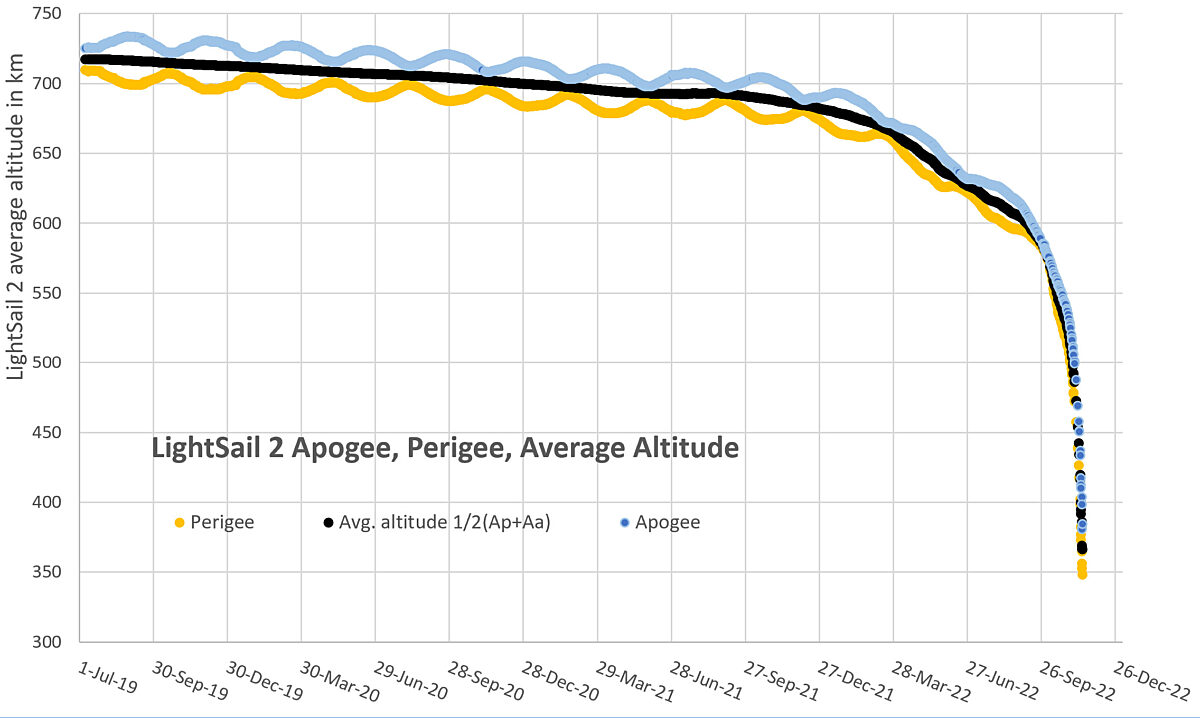

LightSail 2 started at an altitude of around 720 kilometers (about 450 miles). For reference, the International Space Station (ISS) orbits at around 400 kilometers (roughly 250 miles).

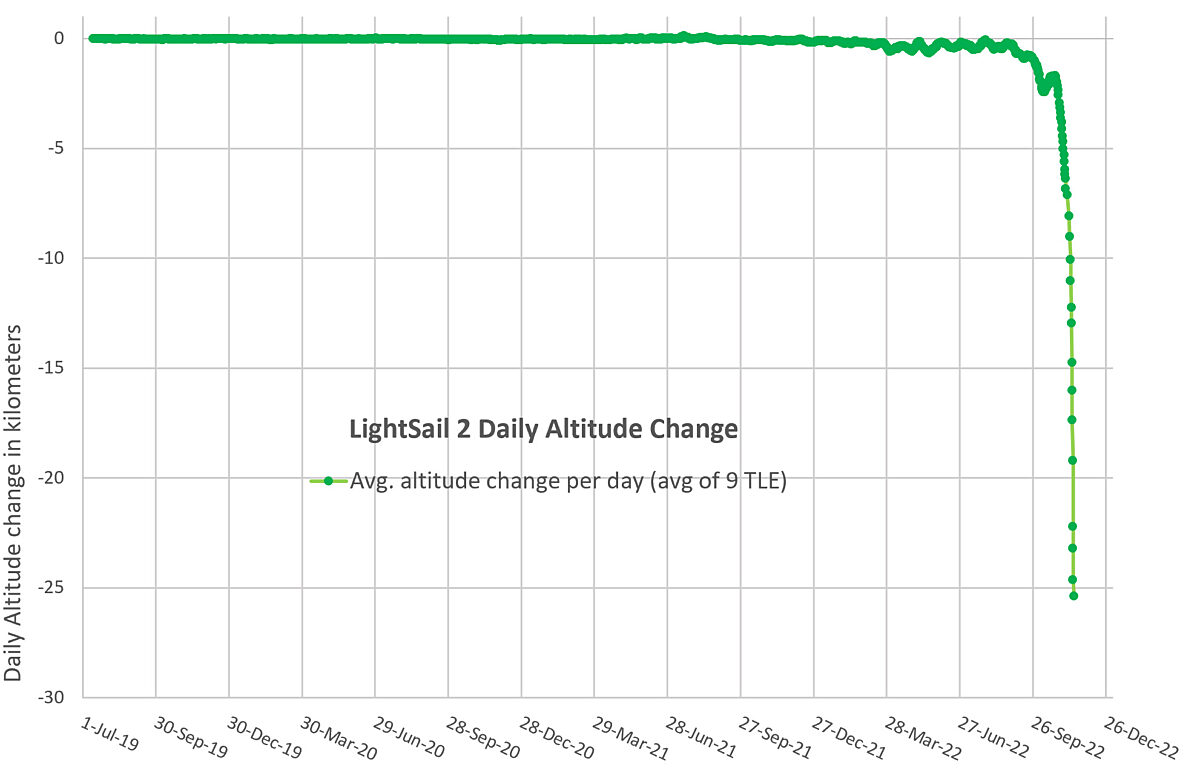

Drag is more significant for LightSail 2 than for most spacecraft because the sail area is very large compared to the spacecraft mass. This is great for solar sailing, but terrible for atmospheric drag. Imagine throwing a rock compared to throwing a piece of paper. Atmospheric drag will stop the paper much faster than the rock. In our case, LightSail 2 is the paper. A spacecraft like the ISS is huge but also massive, more like the rock. But even the ISS has to be boosted higher every few weeks using rockets to compensate for drag. As a spacecraft drops lower, the atmospheric drag gets stronger and stronger. As a result, over the last several weeks the rate of drop has increased dramatically as seen in the graphs shown here.

The increased speed of drop is why “drag sails” are being investigated by various groups including by members of the LightSail team. Drag sails are similar in deployment and materials to a solar sail, but have no intention of ever sailing. They are only to be deployed at the end of a regular satellite’s mission to speed up the deorbiting process in order to limit orbital debris. The descent data we are collecting now for LightSail 2 will contribute a piece to the understanding of drag sails.

As can be seen in the details of the graphs above, during the first years of the mission we were able to successfully use solar sailing to slow the descent. Over brief periods the spacecraft was even able to climb slightly thanks to solar sailing. Overall, it was a losing battle at that altitude. Then, things got worse thanks to another culprit… the Sun.

We launched during a relatively quiet time in the solar cycle. Eventually, solar activity increased, heating the atmosphere, and leading to increased atmospheric densities at the altitudes where LightSail 2 orbited. That marked the beginning of the end. As solar activity increased even more, solar sailing was unable to compete with the increased drag due to atmospheric density increase. The spacecraft was caught in an ever-increasing snowball effect: as the spacecraft got lower, the density increased which caused the spacecraft to get lower even more quickly. This leaves us where we are now: about to enter the atmosphere in a fireball of friction.

Burn Up

Reentry should occur in the next few days unless something changes drastically, for example if the sail collapsed. It is a tricky job predicting deorbits generally, and particularly for a spacecraft as odd as ours in terms of area to mass ratio. Predictions at the time of writing vary from approximately Nov. 15 to 19, but it easily could slip outside that. For reference, amazingly, the spacecraft was at approximately the height of the ISS on Nov. 12, demonstrating the anticipated drag effect being very high.

The US 18th Space Defense Squadron tracks material in space regularly, and various sites including their own generate deorbit predictions based upon that data and spacecraft information. If you want to check the latest orbit or deorbit predictions, here are some ways you can do it:

The Planetary Society mission control dashboard, which shows current apogee and perigee (highest point in its orbit and lowest point, respectively), as well as other information.

Space-Track is a direct source of tracking data provided by the US 18th Space Defense Squadron, but it does require setting up an account.

As our spacecraft hits the thicker parts of the atmosphere at about 28,000 kilometers per hour (17,000 miles per hour), the heat generated will cause the spacecraft to disintegrate and it will appear as a fireball, like a bright meteor in the sky. We don’t know where this fireball will occur, other than it will be between the latitude constraints of our mission of 24° N to 24° S. There is no need for concern if you live in that band. Our spacecraft is small enough that it should totally burn up before ever reaching the surface, so helmets are not required.

The future

As with any successful mission, destruction of the spacecraft is a milestone, but not the end. Our small operations team, no longer having to fly the spacecraft, over the coming months will focus on assembling the data from the entire mission, performing analyses, and publishing and presenting the results publicly and professionally. And of course, we’ll continue to update you into the future as we continue analyses of the LightSail 2 data. We will also report on future solar sail missions that take solar sailing out into the solar system, such as the upcoming missions from NASA. And of course, we will be updating you in the near future after LightSail 2 goes out in a blaze of glory.

Thanks to the many companies and people who were involved with the LightSail program. And of course, a huge thank you to our members and donors without whom the LightSail 2 mission and the LightSail program could not have existed. Sail on!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth