China opened the 2020s by bringing samples back from the Moon and sending its first mission to Mars. The country’s space agency hopes to end the decade by launching a spacecraft to Jupiter that could include a lander bound for the moon Callisto.

China has hinted before that it would like to send missions to the outer planets. Chinese scientists, working with European collaborators, are now solidifying plans for two distinct Jupiter mission concepts, one of which will likely move forward. Both seek to unravel mysteries behind the planet’s origins and workings using a main spacecraft and one or more smaller vehicles.

The competing missions are called the Jupiter Callisto Orbiter and the Jupiter System Observer, or JCO and JSO, respectively. Both would launch in 2029 and arrive in 2035 after one Venus flyby and two Earth flybys. JCO and JSO would study the size, mass, and composition of Jupiter’s irregular satellites—those captured by Jupiter rather than formed in orbit, and often in distant, elliptical and even retrograde orbits—complementing science conducted by NASA’s Europa Clipper and Lucy missions, as well as the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission.

Both JCO and JSO would possibly include CubeSats with particle and field detector payloads to perform the first multi-point study of Jupiter’s magnetic field.

Jupiter Callisto Orbiter

The Jupiter Callisto Orbiter would fly by several irregular satellites before entering a polar orbit around Callisto. This scenario includes a possible lander which, like the Chang’e lunar landers, would provide unprecedented insights into the moon’s formation and evolution.

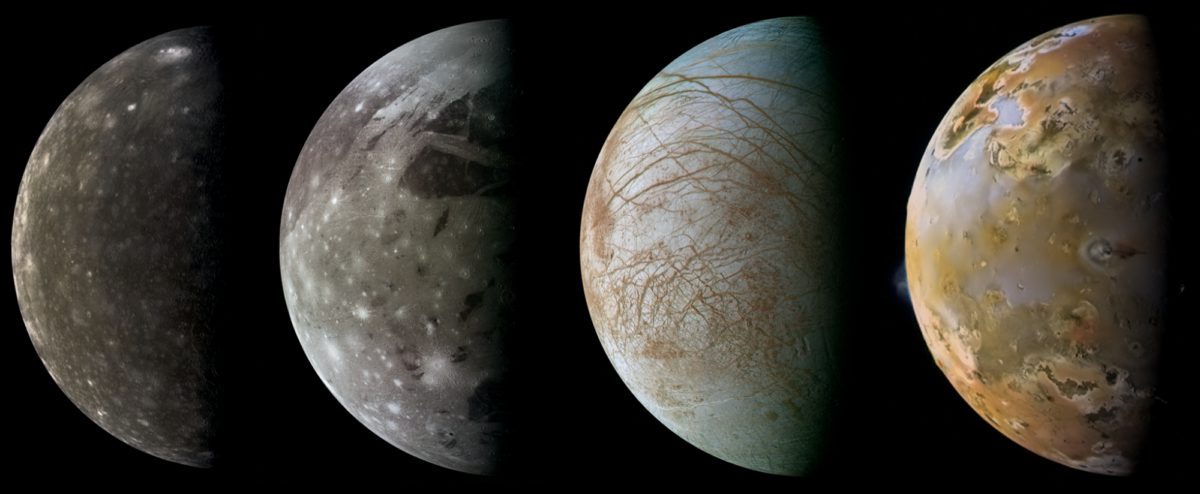

Callisto is the outermost of the four Galilean moons. Its interior experiences less heating due to gravity from the other moons and Jupiter. It likely formed with leftover Jupiter material and has sat mostly dormant since, with only asteroid impacts to modify its surface. The moon thus preserves a history of the early Jupiter system and our solar system at large for a lander to study.

Callisto also has a thin atmosphere with small amounts of oxygen, increasing its scientific allure despite being less glamorous than fellow subsurface ocean moons Europa and Ganymede and volatile, active Io.

Callisto is also the least challenging Jovian moon to land on. A spacecraft requires less fuel to reach it, and it sits outside Jupiter’s intense radiation field.

Jupiter System Observer

The Jupiter System Observer would trade out a possible Callisto landing for a focus on Io. The spacecraft JSO would perform several Io flybys, studying how Jupiter’s gravity tugs on the moon to power its volcanic activity. JSO would also study the mass, density, dynamics and chemical and isotopic composition of irregular satellites and would provide insights into these unique remnants of Jupiter’s formation.

At the end of its tour JSO could be sent to orbit the Sun-Jupiter L1 point, where the planet’s gravity balances with the Sun’s in a way that spacecraft can remain there for long periods of time. From this unique perch where no spacecraft has ever visited, JSO could monitor the solar wind outside of Jupiter’s magnetic field, and survey the irregular Jovian moons from afar.

Will it happen?

Though both missions are ambitious, they have not come out of the blue. A white paper published in late 2016 stated that China will “conduct further studies and key technological research on the bringing back of samples from Mars, asteroid exploration, exploration of the Jupiter system and planet fly-by exploration.”

The JCO and JSO concepts are much more detailed and focused than those previously presented by Chinese scientists. Both build on the engineering successes of the country’s Chang’e missions and Tianwen-1, and are backed by leading, highly accomplished figures from China’s space science sector.

Nevertheless, both missions are ambitious. They require significant advances in electric propulsion, solar power, and spacecraft tracking and communications. Further workshops and meetings on scientific objectives and potential international cooperation are expected to be held by institutions such as the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the International Space Science Institute in Beijing once COVID-19 pandemic restrictions ease.

The Jupiter mission has a tentative final name of Gan De, drawing on Chinese history like the country’s other space exploration missions. Gan was a Chinese astronomer born in the fourth Century BCE who made early detailed observations of Jupiter and, it is claimed, made the first observations of one of the planet’s moons with the unaided eye.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth