Jatan Mehta • Jun 21, 2022

How do planets get rings?

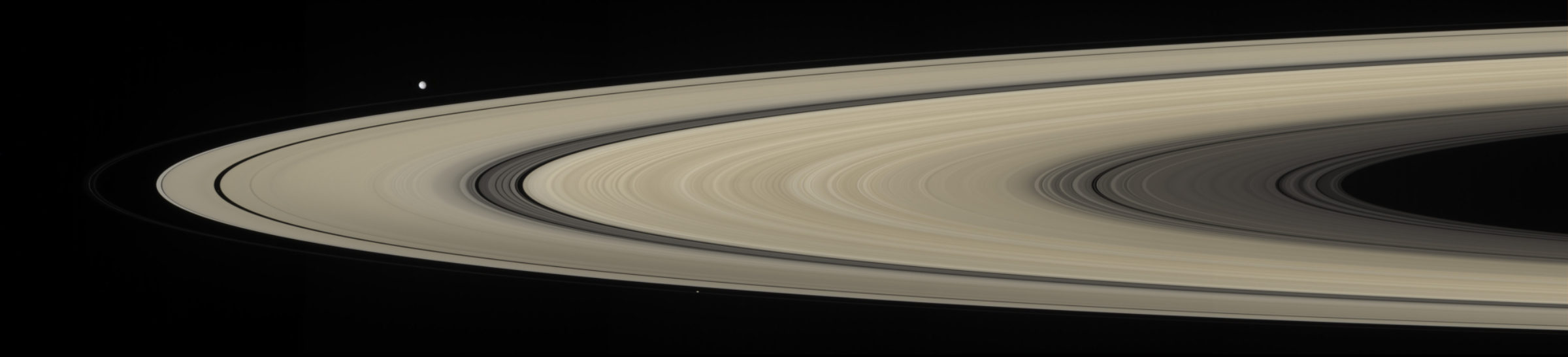

It’s hard to imagine Saturn without rings. Yet that’s exactly what it will be roughly 100 million years from now, a short span of time for a planet born 4.6 billion years ago.

Recent research and measurements taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft have revealed that the ring material — which is mostly water ice — is being gradually pulled into Saturn. Eventually, there will be almost nothing left.

To think that Saturn’s iconic rings, which span the length of 27 Earths, would vanish in a cosmic blip is yet another reminder that our Solar System is a dynamic place. By the time Saturn becomes a pale hazy brown ringless orb, another planet will have adorned a cosmic crown of its own.

Will Mars ever have a ring?

Sometime between 30 to 50 million years from now, Mars’ gravity will break apart its closest moon Phobos. Its fragments will encircle the red planet as rings.

Remarkably, this isn’t the first time such an event would have transpired on Mars. A large asteroid or comet may have impacted the planet shortly after our Solar System’s formation, with the resulting orbital debris becoming rings and eventually clumping into small moons. Scientists think Mars’ gravity ripped the innermost moon into rings again at some point, and so Phobos might just be the latest product of such an ongoing ring-moon cycle.

How and when did Saturn’s rings form?

It’s possible the Saturnian rings formed during or around the time dinosaurs ruled planet Earth. For a long time, scientists thought Saturn’s rings were simply leftover material from the planet’s birth 4.6 billion years ago but recent measurements from Cassini have challenged this assumption.

When the Cassini spacecraft made a number of passes between Saturn and its rings during the mission’s "Grand Finale" in 2017, it allowed scientists to carefully infer the mass of the rings based on how gently the spacecraft was pulled toward them.

It turned out the rings weigh less than Saturn’s small moon Mimas, too low for them being ancient structures formed alongside such a giant planet. Combined with the fact that the rings are still bright and haven’t darkened over time due to incessant space weathering, scientists estimate their age to be less than 100 million years.

Scientists think that Saturn’s rings formed either from a moon getting too close and breaking apart or from collisions of multiple small icy moons.

How are other planets’ rings created?

Our Solar System is host to several other unique ring types. Jupiter’s faint ring system is made entirely of dust particles hurled up into orbit by micrometeorites impacting the planet’s small inner moons. Saturn’s faint and diffuse Phoebe ring is also formed from particles ejected from the namesake moon. Neptune’s outermost ring isn’t even a ring but five distinct arcs, whose particles are probably kept from spreading out due to the gravitational pull of the ring moon Galatea.

Some rings are mysterious. For example, two of the outermost Uranian rings are red and blue, indicating a composition unlike that of the planet’s inner, gray rings as well as that of the Saturnian set. The largest Uranus ring, epsilon, is tens to hundreds of times narrower than those of Saturn, and we don’t know why.

In 2014, astronomers discovered a planet outside our Solar System that appears to have rings 200 times wider than Saturn’s! At 180 million kilometers (112 million miles) across, the rings of this “Super Saturn” — officially named J1407b — span wider than the Sun-Earth distance of 150 million kilometers (about 93 million miles). On the opposite end of the size spectrum, there are the two rings of 10199 Chariklo, a roughly 200-kilometer-sized (about 124-mile-sized) object orbiting our Sun between Saturn and Uranus. How do these colossal and tiny rings form? We’re yet to find out!

Future exploration of our Solar System’s rings

The answers to why the giant planets Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune don’t have as majestic a set of rings as Saturn, at least in the present, ultimately lie in grasping how rings form, evolve, and in some cases, disappear. Sending a spacecraft to excavate chunks from Saturn’s rings and measure their exact composition, and ideally even bring samples to Earth, would anchor the age and origin of Saturn’s rings.

Likewise, figuring out how Phobos formed would tell scientists if it really is part of an ongoing ring-moon cycle at Mars. While no mission is being planned to study Saturn’s rings, Japan’s Martian Moons eXploration mission, or MMX, will study Phobos and bring samples from it to Earth to help scientists ascertain its age and formation.

The 2023-2032 Planetary Science Decadal Survey — a report produced every 10 years by the U.S. scientific community to guide future NASA missions — recommends sending a spacecraft to Uranus as the highest priority. One of the four major scientific objectives of this Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP) mission is to understand the composition, origin, mechanics, and history of the planet’s rings. In the meantime, the recently launched JWST space telescope will observe rings of all the giant planets to spot previously unknown features and help scientists better gauge how they evolve.

The majestic rings of Saturn will wane over time, losing chunks and bits to the planet all the while darkening like soil on our Moon. Even so, Saturn’s tiny icy moon Enceladus will still be erupting water plumes into space to keep the planet’s diffuse E-ring alive.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth