Extraterrestrial artifacts

The search for life beyond Earth is as diverse and wide-ranging as life itself. Some scientists hunt for simple organisms, like microbes, by looking for signs of biological activity. Others search for technology, hoping full-fledged intelligent life is out there with abilities comparable to our own. When most people think of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI), though, they may only think of one thing: scanning the galaxy for communication signals from distant worlds.

But not all searches for alien technology look to other stars. Whether hunting for radar anomalies or unnatural glints from another world, the search for extraterrestrial artifacts (SETA) is dedicated to scouring our very own Solar System. This is what distinguishes SETA from more traditional searches for alien intelligence.

Spotting alien artifacts

Could evidence of alien technology, even long defunct, truly exist within the Solar System? According to Jacob Haqq-Misra, senior research investigator at the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science and a participant in The Planetary Society’s Search for Life Symposium, it’s a feasible possibility, and that means it’s worth scientific investigation.

Consider the timescales involved. The planets of the Solar System have been around for 4.5 billion years, and the galaxy itself is about 9 billion years old. As Haqq-Misra puts it, that’s “plenty of time” for alien life to arise and then leave evidence of itself here. There are a few different scenarios for how exactly that might have happened, according to SETA scientists. Intelligent life might have previously inhabited the Solar System, leaving behind evidence of their presence. Lifeforms from elsewhere might have sent a probe to our system that is still here but no longer works, or maybe they could have even sent a probe here that remains active to this day.

“How would we know?” asks Haqq-Misra. “How would we recognize extraterrestrial technology if we found it?”

This is what motivates Haqq-Misra and his colleagues’ work. They develop and test ideas for what signs of alien technology — also known as “technosignatures” — might look like. Some pieces of evidence, like an intact alien probe, would clearly advertise their extraterrestrial nature. Others would be more subtle, like discovering chemical anomalies in Martian soil that hint at the past use of nuclear fuel or refined metals. Radar surveys could also look for unnaturally shaped objects, searches in visible light could find particularly reflective surfaces that might be artificial, and infrared telescopes could detect waste heat from machines. Many of these efforts could get started using data that scientists already have in hand.

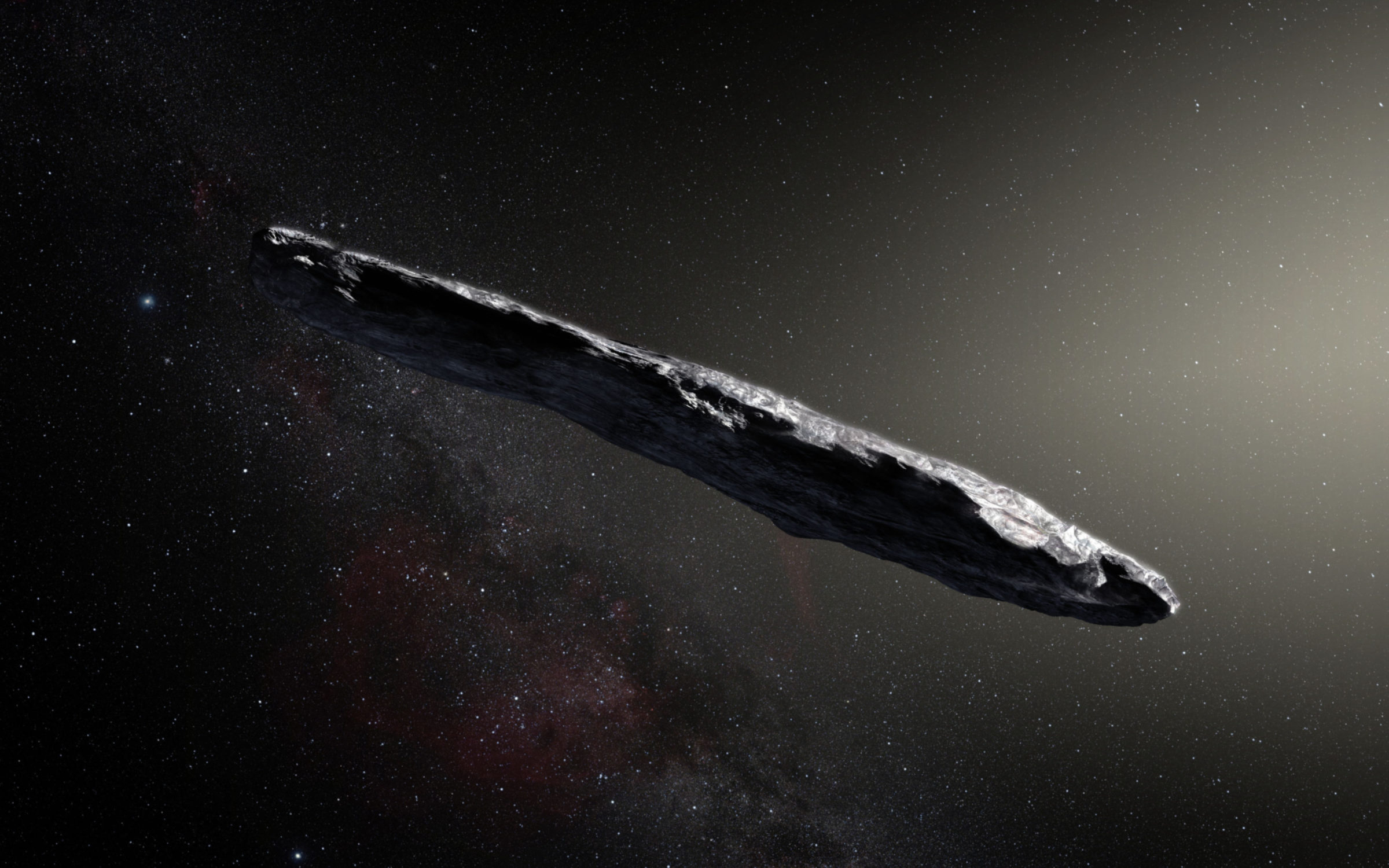

To date, though, Haqq-Misra says he can count the number of SETA research papers on two hands. One group searched for anomalies in a broad survey of the sky. Others performed radio studies of ‘Oumuamua, an unusual interstellar object that would later be best explained as an icy fragment of a planet from another star system. Another looked for artificial objects that share Earth’s orbit. And most recently, a collaboration used machine learning algorithms to search for anomalies on the surface of the Moon.

“That’s it,” says Haqq-Misra. “There’s tons of work to be done.”

A shift toward SETA

For years, lack of interest and recognition from the wider scientific community, especially in the form of funding opportunities, has prevented SETA from doing more. “There’s been stigma,” explains Haqq-Misra. After all, if SETA relies on the notion that aliens at one point interacted with the Solar System, it’s not a huge leap to project that interaction onto Earth itself. But unlike unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) conspiracy theorists, SETA researchers apply the scientific method to data collected in controlled experiments, testing their hypotheses and fitting them into a wider research dialogue.

For Haqq-Misra, this stigma is part of what drove him to pursue these research projects in the first place.

“When you tell me ‘don’t study something,’” he says, “then — well, let’s study that thing!”

Haqq-Misra and his colleagues have been working to shift scientific culture away from this stigmatization. They have spread the word about the potential value of technosignatures through both research papers and conversations with other scientists. The status quo may now be starting to shift. At the direction of the United States Congress, NASA opened up funding opportunities for technosignature research a few years ago. Haqq-Misra’s collaboration received one of the first grants related to nonradio technosignatures.

“Things have changed,” he says. “We can talk about Solar System SETI in a completely detached way from anything in pop culture.”

To search or not to search

Stigma aside, SETA still has its detractors. One issue is timing. The more time an artifact spends in the Solar System, the less likely it is to survive to the present day unscathed. On geologically active worlds, surface artifacts would be destroyed (or at least buried) by volcanism, tectonics, and erosion. Even on inactive worlds, asteroid impacts could destroy most artifacts within hundreds of millions of years. And orbiting artifacts, like lurkers, might eventually be knocked out of their orbits or damaged by impacts and radiation. This makes the long lifetime of the Solar System a double-edged sword: The farther back in the past you consider, the more time alien civilizations would have had to arise and send probes in our direction — but the slimmer the odds that any resulting artifact would have survived to this day.

Another argument is that the odds of any of this happening in the first place — intelligent extraterrestrials existing, intelligent extraterrestrials leaving some piece of technology within the Solar System, and our being able to detect it — are too slim to be worth investigating.

Haqq-Misra responds that there’s no way to know that for sure. As long as his ideas are potentially feasible, he argues, it’s worth testing them to try to learn something concrete.

“I don’t like to assign likelihoods,” he adds, “until we have data.”

The future

SETA researchers have a few milestones they hope to achieve in the not-so-distant future. One is to check whether any artificial structures larger than 10 meters (33 feet) exist on any solid surfaces within the Solar System, which would be no small feat. Another goal is to search thoroughly for any waste heat that might be emitted by technological artifacts on these worlds.

Haqq-Misra is especially excited at the prospect of more machine learning studies of planetary surfaces as well as searches for technosignatures at gravitationally stable regions called Lagrange points, where artifacts would be able to more easily sustain orbits for long periods of time. But these are only a few projects, and SETA is just getting started.

“At this stage,” Haqq-Misra says, “we should do it all.”

The Planetary Report • September Equinox

Help advance space science and exploration! Become a member of The Planetary Society and you'll receive the full PDF and print versions of The Planetary Report.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth