Casey Dreier • Oct 01, 2024

Europa Clipper: A mission backed by advocates

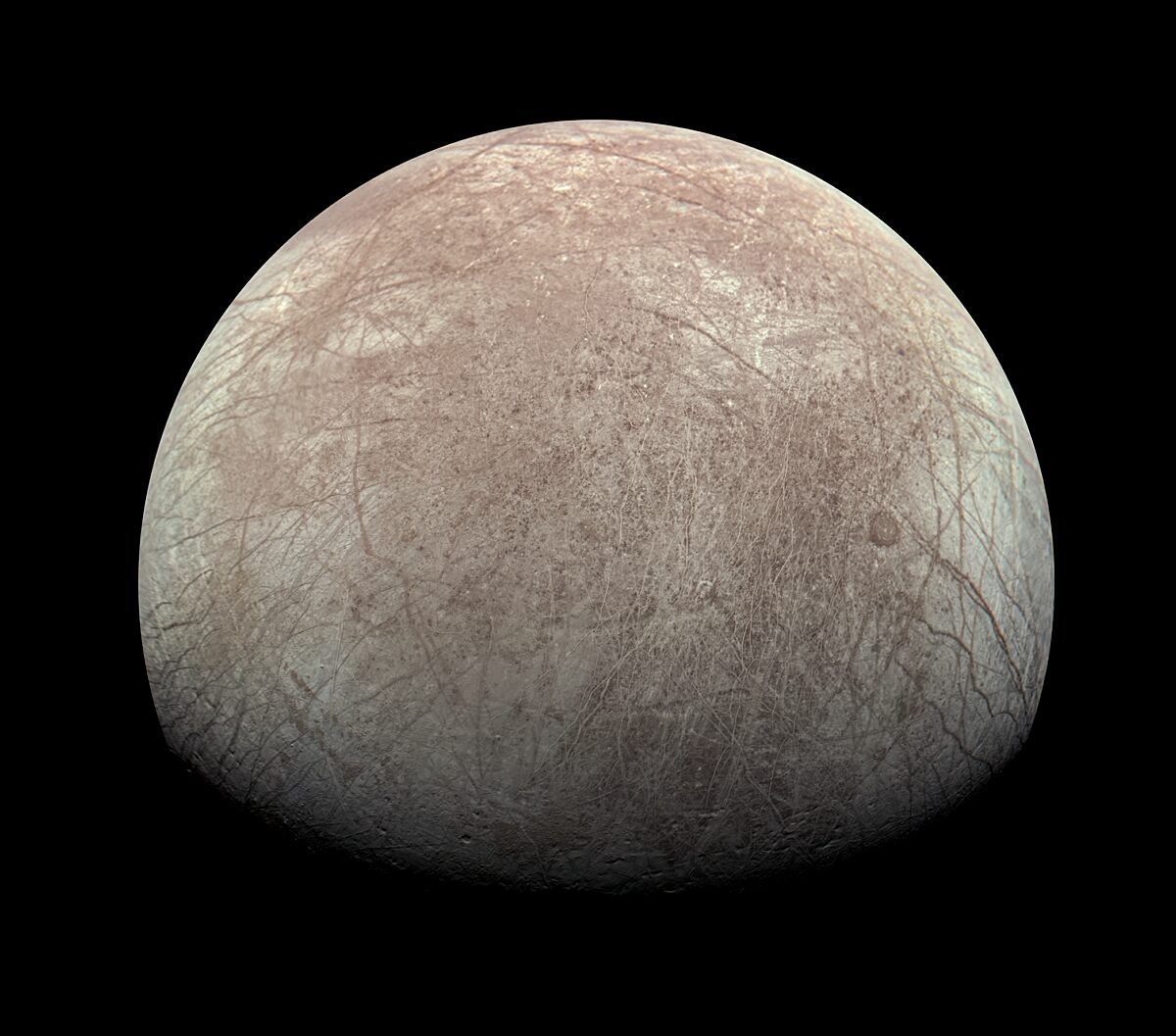

Jupiter's moon Europa is one of the most promising targets in the search for life beyond Earth. In October 2024, NASA’s Europa Clipper will begin humanity's first dedicated mission to understand the habitability of this ocean world. Although exploring Europa has long been a goal of the scientific community, this mission’s journey to the launch pad has been far from easy.

Starting in 2013, The Planetary Society engaged its members and relentlessly advocated for a Europa mission to the U.S. Congress, despite a dismal outlook for planetary science funding. Along with the dedicated work of other advocates, the space science community, and key supporters in Congress, this goal became a reality. NASA ultimately got the funding it needed to design and build this top-priority science mission.

Does Europa have life?

Scientists believe that beneath Europa’s icy crust lies a deep ocean of mineral-rich, liquid water in contact with the rocky surface of the moon. Estimates vary, but this ocean is likely to contain more than twice the amount of water found on Earth. Though no sunlight can reach through the moon’s thick, icy shell to power life, vents that release heat from the moon's interior could exist on its ocean floor. Similar vents at the bottom of Earth's oceans teem with life despite receiving no sunlight and are a candidate for the origins of life on Earth. In addition, this ocean system is thought to be stable over billions of years. Water, minerals, energy, and time — these are the key ingredients for life as we know it on Earth. This makes Europa one of the most promising places in the Solar System for finding extant alien life and more than worthy of a dedicated mission of discovery.

NASA’s shrinking funds stymied a Europa mission

The initial Voyager flybys of Jupiter in 1979 revealed an unexpected surface of Europa that was suggestive of an ice shell over a large ocean. NASA's Galileo mission to Jupiter in the 1990s all but confirmed the presence of a global ocean after multiple flybys of the moon. These discoveries helped establish a dedicated Europa mission as the top priority of the very first planetary science decadal survey in 2002. Unfortunately, funding for a mission failed to materialize due to the high cost of building a hardy spacecraft to endure the extreme radiation at the Jupiter system and NASA deciding to prioritize other destinations amid a declining budget in the 2000s.

A Europa mission was once again among the top priorities of the second planetary science decadal survey. In 2012, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory outlined a refined Europa mission concept based on lessons from Cassini’s tour of the Saturnian moons: the spacecraft would orbit Jupiter, not Europa, but fly by the moon dozens of times. This provided nearly all the scientific return of a dedicated orbiter while minimizing the worst of the radiation.

But it wasn’t enough. At that time, NASA’s budget was shrinking. A divided government had all but frozen Congress and had forced across-the-board cuts to discretionary spending. NASA again prioritized other missions instead of Europa. The agency’s Planetary Science Division had just lost 15% of its budget in a single year, with NASA projecting continued cuts and a minimal program of solar system exploration for years thereafter. The Planetary Society strongly objected to this retreat from planetary science, a situation characterized by other experts at the time as a “fade to black” for U.S. exploration of the Solar System.

Despite this, in January 2013, during a strategy session in preparation for the upcoming NASA budget cycle, The Planetary Society made a bold decision: we resolved to fully commit to a flagship Europa mission as one of our top advocacy goals.

The Planetary Society’s fight for Europa Clipper’s survival

For the following three years, The Planetary Society rallied hard for a mission to Europa. We published Europa-themed issues of The Planetary Report and countless articles, op-eds, and popular Reddit AMAs. Our President testified before congress. We held numerous standing-room-only events on Capitol Hill to promote the mission. We met with members of Congress of both parties to build broad support for the mission. We worked closely with partner organizations around the country to coordinate our messaging. We released open letters to President Obama that received over a million views on YouTube. Our CEO, Bill Nye, even discussed a Europa mission with Obama directly during a ride on Marine One before an Earth Day event in 2015. We met frequently with John Culberson (R-TX), a member of the House of Representatives who fully understood the profound scientific implications of exploring Europa and was its staunchest supporter in Congress.

Planetary Society members also participated en masse. Between 2013 and 2016, our members sent 384,949 messages to their representatives in Congress and the White House to support planetary exploration and Europa Clipper — our most successful grassroots effort ever.

PLANETARY SOCIETY MEMBERS SHOWED UP FOR EUROPA Between 2013 and 2016, Planetary Society members sent 384,949 messages to Congress and the White House in support of a Europa mission.

Planetary Society CEO Bill Nye Advocating for a Europa mission to Congress Ten years ago, Planetary Society CEO Bill Nye spoke to elected officials and staff at an event in the U.S. Capitol. At the time, NASA was reluctant to request funding for the mission. But Congress listened. In its 2015 budget request, NASA formally requested $15 million for the Europa Clipper mission. Thanks in part to ongoing advocacy efforts, the mission is finally a reality.

After years of relentless pressure and spurred by the discovery of potential ocean plumes emanating from Europa, NASA finally acquiesced and formally requested funding for a Europa Clipper mission in 2015 — though only a meager $15 million, far below what was needed. John Culberson, then the powerful chair of the House Commerce, Justice, and Science Appropriations Subcommittee, gave NASA $100 million instead. The following year, NASA asked for another paltry amount, slow-walking the mission despite obvious political support. Culberson provided $175 million. The Obama White House resisted until the end, with its final budget requesting a mere $49 million for fiscal year 2017. Culberson ensured the project got $275 million. It wasn’t until the 2018 budget request that NASA finally asked for the funding it needed to launch Europa Clipper by 2024. Since then, Congress has obliged the request every year.

Europa prepares to make history

The Europa Clipper mission is now due to launch as early as Oct. 10, 2024. It will arrive at the Jupiter system in 2030 and make at least 45 flybys of Europa.

An ice-penetrating radar instrument will map the moon’s ice and the possible lakes within. Other instruments will measure the moon’s magnetic properties to confirm the presence of the subsurface ocean. They will also help determine the depth of Europa’s icy shell and ocean. Two sets of cameras operating at different wavelengths will map the moon’s surface and search for plumes. Another instrument will look for small particles ejected from Europa that could trace potential plumes. Two spectrometers will measure the composition of Europa’s surface and atmosphere to get a sense of the makeup of its hidden ocean. If possible, the spacecraft may even soar through plumes of water that shoot through the moon’s crust. Although NASA has stated that Europa Clipper is not officially a life-detection mission, it still holds the potential to expand our understanding of life elsewhere in our Solar System.

This mission didn't just happen. That we are going is the outcome of decades of effort by thousands of people, the dedicated scientists and engineers on the Europa Clipper mission most of all. The Planetary Society and its members are proud to have played a role building a firm political and public foundation to support the endeavor. Europa does not give up its secrets easily, but now, for the first time in human history, we will seek them out.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth